LION’s products can mean the difference between life and death for the customers of this family-owned company, which makes protective clothing and training equipment for firefighters. From its origins in 1898 as a horse-and-wagon operation selling clothing to farmers in Dayton, Ohio, LION turns out everything from Teflon suits worn by medical personnel transporting Ebola patients to mini metropolises spanning 20 acres that can be set on fire to train fire departments. Fun fact: LION also makes the gear worn by the actors on the NBC show “Chicago Fire.”

LION’s business brings together complex logistics, creative thinking and the ability to manage high-pressure situations — not unlike the customers it serves.

Transcript

WAILIN: It’s a Monday morning and 65 Chicago Fire Department candidates are gathered at the city’s fire academy for a crucial part of their training. A few months ago, these men and women were measured for what’s called their turnout gear — their protective coats and pants. Today, they’re trying everything on under the watchful eye of academy instructors.

INSTRUCTOR: You’re gonna wear it up to 10 years before you get a new set, okay? So if something is not right, you’re not being prickly about it right now. We need to know if something is not right. Don’t hesitate to say something. Everybody understand that?

GROUP: Yes sir.

INSTRUCTOR: Trust me, we won’t always be as friendly in the next couple weeks, right? This is the day we need this stuff done right…

WAILIN: The candidates are making sure their names are spelled correctly on the backs of their coats, that their suspenders are the right length and they have enough coverage when they bend over or get down on all fours.

INSTRUCTOR: What I’m looking for is nothing that is too tight or that I’m absolutely swimming in. It’s going to be big. Think about it—unfortunately, a fact of the job is you are going to gain weight. Right? On this job. My point is that a little play room is fine in there because you’re gonna wear a sweatshirt, it’s gonna be 40 below sometimes and you’re not gonna be in a little thin t-shirt, so a little room inside that coat is fine. You just don’t want to swim in it, please.

WAILIN: There’s someone else on hand for the sizing exercise. Mike Kucharski is a representative from LION, the company that manufactured the gear for these firefighter candidates.

MIKE: This is the first time they’ve ever put this stuff on. Some of these guys, this is even kind of new to them, wearing this stuff, so we’re now just gonna check it out, see how it fits, make sure everything’s right, that they can move and do their work with this garments on.

WAILIN: Outfitting fire departments across the country is a big responsibility, and LION’s been doing it for almost a half century, using protective materials first developed for the Apollo space program. The company itself dates back to 1898, when its founder started selling clothing to farmers from a horse-pulled wagon. Today, the great grandson of that itinerant salesman runs a global company that provides firefighting gear, training equipment and logistical support for first responders and the US military. Find out how LION went from farmers to firefighters on this episode of The Distance, a podcast about long-running businesses. I’m Wailin Wong. The Distance is a production of Basecamp. The brand new Basecamp 3 is everything any team needs to stay on the same page about whatever they’re working on. Tasks, spur of the moment conversations with coworkers, status updates, reports, documents and files all share one home. And now your first basecamp is completely free forever. Sign up at basecamp.com/thedistance.

STEVE: This is a picture of Version 1.0 of LION. This is my great grandfather right here, standing next to one of his customers in front of a horse and buggy with Dayton Department Store on it.

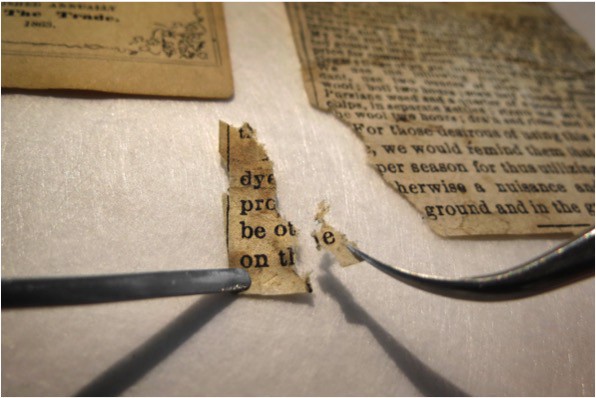

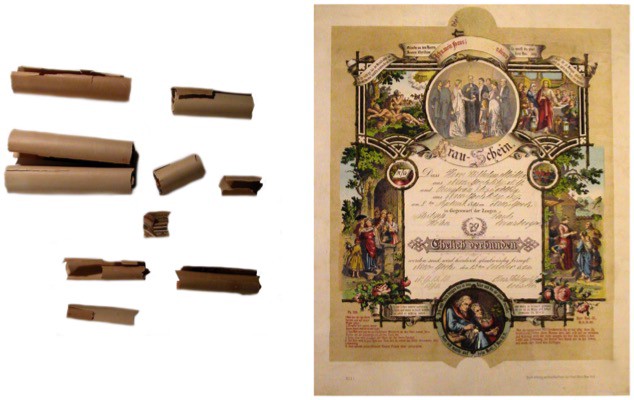

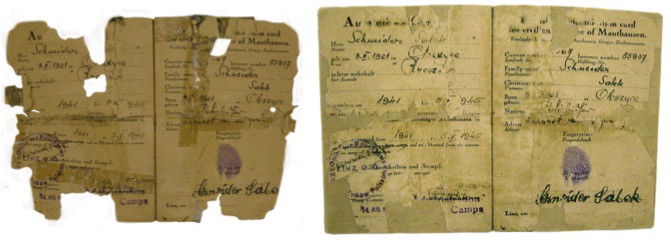

WAILIN: That’s Steve Schwartz, the CEO of LION. We’re in a conference room at LION’s headquarters in Dayton, Ohio that’s filled with mementoes from the company’s history. The artifacts show LION’s evolution from a horse and wagon operation originally called Dayton Department Store to a bricks and mortar clothing retailer in downtown Dayton to a business specializing in uniforms for service station workers.

STEVE: This is a framed set of catalogs from really I would call Version 2 of LION, which is when my grandfather went into the corporate apparel business and we were selling uniforms to service station attendants. So you see, this is back I think in 1941, he was selling a shirt and trousers for the huge price of three dollars and 95 cents.

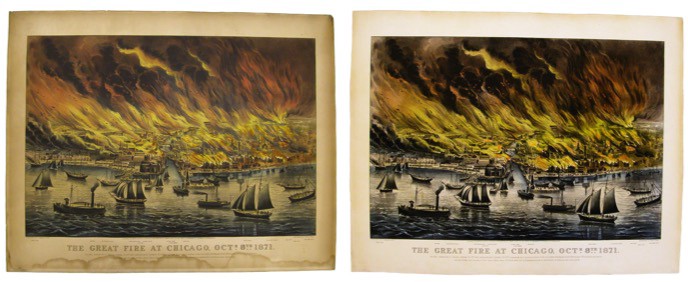

WAILIN: Most of the service station uniforms came in blue, and LION’s salespeople started noticing that a lot of firefighters also wore blue uniforms. That epiphany got the company into the fire business, initially making what’s called station wear, or the shirts and pants that firefighters wear when they’re not out responding to a call. Today, LION’s customers include the fire departments in cities like Chicago, Honolulu, Phoenix and Toronto. It also makes the gear you see on the NBC show “Chicago Fire.” The manufacturing process is very complex. Even something that seems simple, like an exterior coat pocket, can be customized thousands of ways at LION’s factories in southeastern Kentucky.

STEVE: We have probably over 10 thousand different types of pockets. We make pockets for putting your hands in to stay warm. We make pockets to store your mask, for holding your radio, so there’s just a really infinite number of potential shapes and sizes that we can make. So we’re really in the mass customization business to that extent, and that is something that makes us more valuable to our customers, which is good, but it adds a lot of complexity to the manufacturing process. The average order size for us, even though we’re making tens of thousands of these a year, the average order size is, I think, between four and six sets of gear.

WAILIN: There are 30,000 fire departments in the US and most of them have 75 people or fewer, so each order is small and different from the next. But all of LION’s products undergo the same rigorous testing. Threads have to stay intact up to 536 degrees Fahrenheit before melting. Helmets, boots, zippers and snaps have to withstand 500 degree heat for five minutes without dripping or igniting. LION uses materials like Kevlar and Nomex, which were developed for spacesuits worn by astronauts in the Apollo program. In the case of its CBRN suits — that’s chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear — LION is just one of two companies licensed to use a particular kind of Teflon. In 2014, US medical personnel transporting Ebola patients wore LION suits. The company doesn’t make Kevlar or Teflon, so it’s somewhat reliant on its suppliers to keep coming up with technological improvements. That motivates LION to actively seek out the best stuff for its gear.

STEVE: A lot of materials in our products are materials that were developed for other purposes beside firefighting that we have found and have adapted to firefighting. We are the only company in our industry that uses a flame-resistant closed-cell foam for padding that does several things. First, it obviously cushions your knees and elbows because it’s foam. Number two, it doesn’t absorb water in the process like open-cell foam would or just fabric would. And so that was something we found that was being used for aircraft insulation.

WAILIN: There’s a kind of tension in what LION does. It’s constantly looking for the newest and best materials, but it also has to sell that technology to customers who are historically resistant to change.

STEVE: The fire service and first responder business, because they are inherently in a business where conservatism is important, take a long time to adopt new technology, but we really feel like our collection of products with the technology we offer are very, very unique.

WAILIN: This challenge and opportunity are also present in LION’s newest and fastest-growing line of business, which is making firefighting training equipment, called props. One example is a tray of water that’s ignited by propane and equipped with sensors that react to water being sprayed on them. LION can build things like a car or a stove around the tray to simulate real-life fires. Another prop is a portable panel, about the size of a small flat-screen TV, that lights up with digital flames and is linked to a smoke generator. The fake fire can be put out with an extinguisher outfitted with a laser pointer or a weighted hose with a digital nozzle.

STEVE: A firefighter can walk into a room and with our smoke generator in operation in conjunction with this panel, see a fire in a room full of smoke. But the fire’s actually a digital fire, and using microprocessor controls, we can actually have the fire spread to multiple panels, so we can have the fire sort of engulf a whole room and have the appropriate smoke go with it.

Here’s the fire extinguisher. It’s got a pin in it, just like a normal fire extinguisher. And then the instructor would push the button to start and here we have a fire, so I’m gonna pull the pin out…Tells me it took 10.9 seconds to extinguish the fire.

WAILIN: Is that good?

STEVE: That’s pretty good. Yeah, yeah. I’m pretty expert.

WAILIN: The digital props allow firefighters to safely train in environments that are more controlled and reduce their exposure to carcinogens, while only making small sacrifices on the realism side. And the props can be placed within larger and more complex scenarios. Steve shows me a photo of a 20-acre training facility in the Netherlands made up of realistic concrete structures.

STEVE: I call this Disneyland for firefighters. And so we actually create sort of mini cities that have lots of different buildings and structures. The picture you see here, for instance, has a small sort of small petrochemical complex with tanks and piping. We have a rail car simulation where the rail car’s leaking or a flange could catch on fire. We have a ship simulation where we have an engine fire inside the ship. To the far left, you can barely see it there, we have an underground parking garage. We can have the flames go up the wall and over the wall. We can create what’s known as a flash over effect, which is very very dangerous for firefighters. Essentially the air becomes so hot that the air itself kind of explodes.

WAILIN: LION has built these mini cities in places like Shanghai and Melbourne. It doesn’t have any facilities in the U.S., although it’s hoping to. In contrast, LION’s firefighting gear business is heavily concentrated in the U.S. because it’s had some difficulties expanding that division overseas. Steve likes to be diversified, both in terms of geographic markets and the company’s suppliers. LION has also branched out beyond manufacturing, into software that helps the U.S. Marine Corps track equipment for individual soldiers.

STEVE: We’re managing $2.5 billion every day of Marine Corps equipment through a software system that keeps track by individual soldier what they have been issued, and when they return it, and when they return it, what condition it’s in. And that includes everything from body armor to helmets to canteens to backpacks, sleeping bags—and we won that contract.

WAILIN: Part of LION’s contract involves running 20 facilities around the world where Marines shop for what they need.

STEVE: They literally take a grocery shopping cart and they go through the aisles of our grocery store and they, as I say, squeeze the Charmin to see which of the products they want. And this used helmet looks like this and do I want that, and this flak jacket, is that good enough, and they come back to our station with their grocery cart full of products and then they actually sign on a credit card signature pad, I have taken these items out and I’m financially responsible for them and will return them.

WAILIN: LION doesn’t make any of the Marine Corps gear even though it has expertise in making protective clothing for fire departments. Steve believes that when it comes to the military world, he can compete more effectively and make a better profit by tackling the logistical end, rather than the manufacturing side.

STEVE: That’s always a surprise to people because again, they think of us as a manufacturing company, but since I’ve been CEO I’ve always felt that we shouldn’t limit ourselves to the idea that we have to make everything to be successful.

WAILIN: Steve became CEO in 2006, taking over the position from his uncle on his mother’s side. He had joined LION after business school and worked his way through different roles, from client services to factory operations to sales. He’s cognizant that the products his company makes can mean the difference between life and death, or life and severe injury, for his customers. And taking another step back, he sees firefighters as playing an important role in the economic well-being of towns and cities. LION is working with an NGO to collect used gear for fire departments with fewer resources. There’s a financial motivation behind the program, since LION hopes the recipients of the used gear will eventually become buyers of new equipment. But there’s a social responsibility component too.

STEVE: We figure in our industry there’s probably about a million and a half cubic feet of gear that’s going into a landfill or dumpster that we think much of which could be reused in a country for a fire service either that’s developing or wants to start. What I’m really passionate about is the idea that a fire department is really kind of part of the social safety net of a community. You can’t really have economic development if you’re worried that your building or your business is going to burn down.

WAILIN: And it all comes back to outfitting individual firefighters, like the 65 Chicago Fire Department recruits trying on their turnout gear for the first time. If Steve has his way, LION will be providing their uniforms for their entire career.

INSTRUCTOR: Everybody okay there? So hey, arms up again, move around, feel how it feels in the shoulder. Bend over like I was talking about ’cause I want to see the coverage with your coat on. Perfect, perfect, good, good…

WAILIN: The Distance is produced by Shaun Hildner and me, Wailin Wong. Our illustrations are done by Nate Otto. The Distance is a production of Basecamp, the leading app for keeping teams on the same page about whatever they’re working on. Your first Basecamp is completely free forever. Try the brand new Basecamp Three for yourself at basecamp.com/thedistance.