Photo: Marcus Jeffrey

“I think that ‘Designed by Apple in California’ is the most brilliant thing to ever appear on a package,” I wrote on the application-site that was mentioned in yesterday’s post on sites that landed jobs at 37signals. SvN reader Michael P. Mills asked:

I agree, that line is brilliant and I remember the first day I ever saw it.

I am very curious to hear why you believe that “it is the most brilliant thing to ever appear on a package”.

This simple tag has appeared on nearly every Apple product or package in at least the last decade. (I couldn’t find any definitive answer as to how long it’s been in use, but I remember it distinctly on the iPod packaging in early 2000’s.)

What’s great about this phrase is that it’s powerful on more than one level.

Presentation

Designed by Apple in California is usually presented dramatically and in isolation. Often you see it after opening a flap or unfolding a panel. It stands alone as a single line of type on a solid field. There is never anything that distracts from it. The early cube-shaped iPod packages were the best at this. You’d remove the sleeve, unfold two panels, and there it was. The next fold revealed the device. That I still remember this sequence says a lot about how powerful the experience was.

Emotion

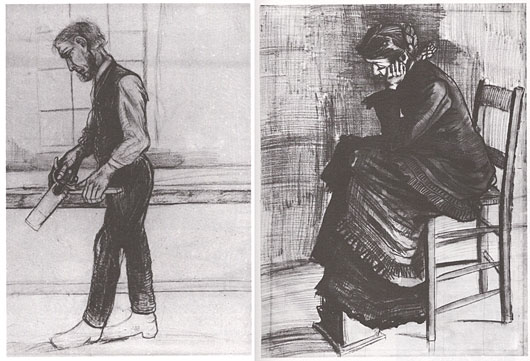

The copy itself, evokes feelings of artistry. Like this object was meticulously crafted, carefully wrapped, and bought safely to your door. It feels human, as if you received it directly from the person who so lovingly made it. Craftsmen sign their work. Master Bladesmith Bob Kramer puts his name on all his knives. Vermont Furniture Designs puts its name inside each dresser it makes. Edward Tufte advises designers to always put their name on what they make — it shows that you care about the finished product and take responsibility for it. That’s the feeling I get from this line.

Also, it wasn’t “Made by Apple in California,” it was Designed. I can’t think of another company that holds design in higher esteem or even one that touts every product as designed, not made. This might be the best expression of the company’s mission available.

California

The design comes from Cupertino, from people who obsess over it. Items may be manufactured in China, but they’re designed by Apple headquarters. And that matters to people. Plus, California evokes magic for many people — especially the California of the mid-1970’s that gave birth to Apple Computer and really, the entire personal computer revolution. Warm weather, surfing, celebrity and a free-wheeling easy lifestyle in the age of American Graffiti are not such bad things to associate your company with.

Marketing that doesn’t shout

There is an adage in graphic design that goes something like this:

If you want to make something stand out in your design, make it big. If it needs to stand out even more, make it bold. Still not enough? Make it red.

Big and bold and red epitomize the lazy designer because it always works but shows no imagination. Marketing is usually full of big and bold and red.

Yet here, Apple goes subtle. The careful design makes the statement even more powerful. Apple conveys the importance of this phrase by isolating it, so it never can be missed. It never has to compete with other elements. It’s small and elegant, just like the devices themselves. It is revealed dramatically and unexpectedly. All of these devices make this statement loud and clear without Apple ever having to raise its voice. By doing that, it sets the tone for the actual product and experience contained within.