In January of 2006, a young comedian with a taste of doing stand-up in college, moved to New York to make it big.

I got $200 and dreams, let’s do this thing.

But following a stretch of barely getting by and sleeping on the subway, he moved back to Chicago by May of the same year. So what happened to him? Did he give up?

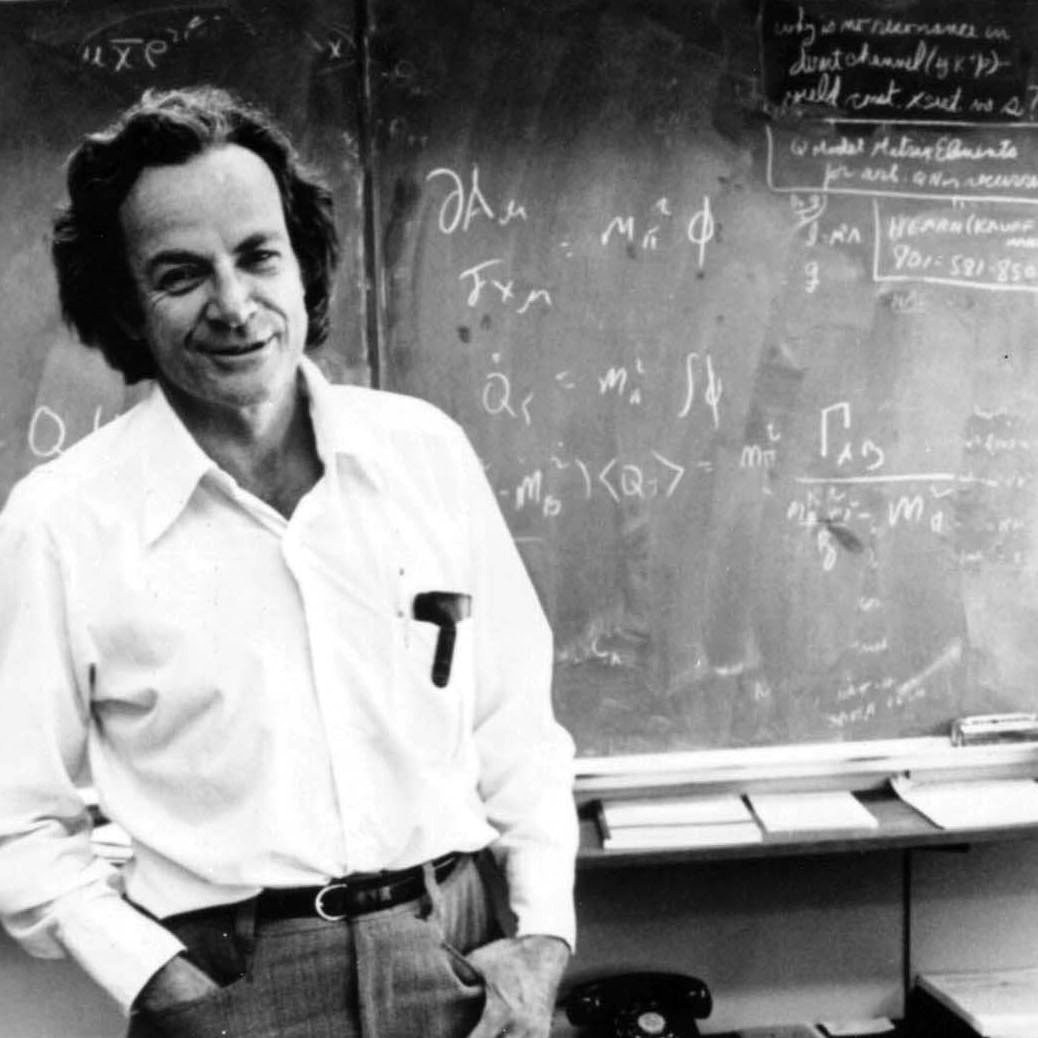

Richard Feynman, one of the greatest physicists and thinkers of our time, was devoted to breaking things down into first principles. He’d strip a problem or idea down to the basics he first could prove to be true before building more on top.

For example, instead of studying theory and papers from other physicists to prepare to take his oral exam for his graduate degree, Richard opened up a blank notebook, titled it “Notebook Of Things I Don’t Know About”, and essentially wrote his own physics text book. Over the course of weeks, he built up his knowledge of physics from the very beginning of what he could prove to be true.

During the exam he was asked the color at the top of a rainbow. Instead of using the ROYGBIV acronym most of us learn in grade school, he used the refractive index of water, wavelengths, and physics to calculate the actual colors.

First principles is why I’m so interested in stand-up comedians, who are often solo acts, and survive on their own good ideas and delivery to make people laugh. They don’t have teams or venture capitalists doing things for them. They can’t make excuses that one of their co-founders blew up the business.

Our comedian had a recent interview where he shares several first principles that have helped him on his journey and we can learn a lot from them…

Generic problems

A lot of my standup is argument: Why are we doing this? Why do I have to do this? Why? Simple example: My buzzer rings yesterday. I go downstairs. UPS has a package. And he’s like “What’s the apartment?” “The one you were just ringing”

Peter F. Drucker wrote The Effective Executive in 1966 but much of it still rings true today. How do the best of us seem to get so much done? Well there are several things, like picking battles that matter and working from strengths. But one that stands out — working on generic problems.

Drucker: By far the most common mistake is to treat a generic situation as if it were a series of unique events; that is, to be pragmatic when one lacks the generic understanding and principle.The effective decision-maker, therefore, always assumes initially that the problem is generic. He always assumes that the event that clamors for his attention is in reality a symptom. He looks for the true problem. He is not content with doctoring the symptom alone.

This comedian is great at observing how even a UPS delivery driver presents a generic problem many of us face.

One of the first things I did at Highrise was to stop all the “favors” we were doing. Customers would come in and ask for unique things they needed handled in their account. Things that could only be done by a developer using our backend tools. It took up a ton of time, but even worse, it forced us to focus on symptoms.

When we instead focused on the problems they represented as generic issues many customers were going through, we were able to make big changes that made a lot of people happier. For example, “Company Tags” is a feature we just added because I refused to run a script for just a single account.

Of course it’s a balance. We still find ourselves doing one off favors, and in my opinion still too many. But we get a lot done at Highrise with a very small team, and this is a big reason: when a support case comes in, our first thought isn’t to delight this specific user at this specific moment, but to figure out if what we’re looking at could be generic and what we can do to stop it from happening in the future for more people. It’s hard to pull off, because we might actually disappoint a user at first, but the time we get back can be used to make a much larger impact for our customers.

Ask

On meeting Mitch Hedberg.

I got to do a show with him, actually, in 2005, a few weeks before he passed. He had a couple nights at Zanies in Chicago. I didn’t really have any social grace at that time. I was 22. I just asked him if I could get a guest spot. And he put me and a couple other comics on for five minutes in front of a sold-out crowd.

An opportunity he just had the guts to ask for. No reason Mitch would say yes, but what would hurt to ask?

Over and over again I see opportunities come my way just because I wasn’t afraid to ask. Our first deal at my first startup resulted from a cold email asking if someone would like to chat. I didn’t expect a reply. Instead, it turned into 35k in revenue, which made all the difference for us when we were making nothing.

Even what I’m doing today was because awhile ago I decided to take a shot and email Jason Fried of Basecamp to see if he’d like to chat about product development and share ideas about what I was working on. No reason I expected him to say yes. But he did. Over time that relationship turned into me taking over Highrise.

Didn’t know me from shit. And I killed it.

Sometimes you just take a bunch of shots and see what happens.

Perspective

Daniel T. Gilbert, a psychologist at Harvard, published an article in 2013 about the “end of history illusion”. They found significant evidence that humans are really bad at predicting our own change. Sure, when we look back a decade we see how much we’ve grown and learned, but when we try to predict how we’ll change over the course of the next decade, most people think they’ll change very little. Our tastes, ideas, hobbies, etc. will just remain the same. Then, give us another decade, and we’ll look back, and again we’ll see how naive we were.

That’s a ripe place to make mistakes. The feeling of not changing makes us resistant to looking for help and new ideas.

We launched a brand new marketing site for Highrise in November of 2014. Of course, I wanted to test the new site to make sure it converted new customers as well or hopefully better than the old site.

And believe me, I know split testing.

I’ve been split testing sites for decades. I know all the tools available. I’ve even written a split testing utility for Ruby.

So as we rolled out the new site, we first tested. And as soon as we saw a statistically significant increase in signups, we deployed the new site to all our traffic. And on we went.

Now, in a new year, we started reviewing how Highrise is doing compared to Highrise of the past, and even more, how does it compare to Basecamp?

This time, to get some help with looking at historical data I reached out to Noah, the data scientist at Basecamp, who sent over a thorough analysis.

Active users — up. Retention of trial customers — up. Yearly retention of users — up.

Awesome. But…

“Nate, the revenue mix is totally off.”

We had increased free signups, but decreased paid signups. The new marketing site has a greater conversion rate but only because we included free signups in our test metric. Overall, we lost a bunch of potential paid customers because of our changes.

Uggh.

The subsequent fix to our marketing site took under 3 hours. Now our plans page looks a lot like the original site again. And it increased our revenue by 63%.

How did I not see this? Hubris. I should have brought in Noah from the get go. I did a poor job of predicting how much I still needed to learn and change in this new role and business.

Our comedian shares in a recent interview with NPR regarding his time sleeping on the subway:

“It was just really goofy on my part,” he admits, in retrospect. “ ’Cause I didn’t have to do that. I could have — one, I could have made up with my sister and apologized for popping in on her place like that. But I was too cocky. And two, I could have just gone back home to Chicago. So it was just goofiness on my part. I don’t glamorize it, like, ‘Oh, I was living on the train for my dream. It wasn’t; I don’t look at it like that at all.”

Now he realizes how easily he could have fixed his situation early in his career. If only he knew then what he knows now. How cocky he was. How easily he could have asked for forgiveness or more help. If only we could predict how little we know 🙂

But maybe just knowing Gilbert’s research is enough. Maybe if we just assume we really never know enough, we’ll make some better decisions.

When I see a comic make headway in the world, like Louis C.K or Mitch Hedberg, they get my attention. Of course because they’re funny. But how do they do it? How do they stay relevant and find new good ideas? How do they market themselves?

Hannibal Buress is a great example. He was that young cocky kid at 23 who moved to New York only to end up sleeping on the subway and moving back home. Today though we can find Hannibal on comedy specials, TV, touring the world, and we can learn a lot from his recent interviews with Scott Raab in Esquire and NPR’s David Greene.

If we understand what’s worked for Hannibal as he struggled to create a life and business in his craft — like looking for generic problems, asking for help, and realizing how little we know — perhaps we can use those as first principles in our own lives, teams and organizations.

P.S. It would be awesome to meet you on Twitter, or see the awesome new stuff we’re doing at Highrise.