This is the first post about the upcoming major release of Basecamp 3.

We’ve been working on Basecamp 3 for over a year now, and some of the concepts can be traced back to explorations we started a couple of years ago. We’re in the home stretch and we’re excited to let it loose.

Over the next month or so I’ll be sharing some of the key ideas behind the all-new version of Basecamp, as well as screenshots, design decisions, strategic decisions, and stories of the development of the third complete ground-up rethink and redesign of Basecamp in 12 years.

The first place I want to start is one of the fundamental pillars of the new product design: Work Can Wait.

If you’ve used a modern chat, collaboration, or messaging app, you’ve probably noticed that there’s a growing expectation of being available all the time. Someone at work hits you up on a Saturday, you get the notification, and what are you supposed to do? You could ignore them, but what’s the expectation? The expectation is “if you’re reachable, you should reply.” And if you don’t reply, you’ll likely notice another message from the same tool or a tool switch to try to reach you another way. And then the pressure really mounts to reply. On a Saturday. Or at 9pm on a Wednesday. Or some other time when it’s life time, not work time.

I don’t believe tools are at fault for this — tools just do what toolmakers build them to do. But I do believe toolmakers can build tools that help you draw a line between work and life. We’ve baked these good manners into Basecamp 3 with a feature we’re calling Work Can Wait.

Like other modern messaging tools, Basecamp 3 sends notifications in-app, via push notifications on the desktop or via a native mobile app, or via email. Where they show up depends on what you’re doing and where you are, but regardless, Basecamp tries to get your attention when someone asks for your attention.

That’s fine during the work day. Basecamp 3 lets you snooze notifications any time to give you a break for a few hours, so that’s good. But what about if it’s 8pm on a Monday night? Or on a weekend? You don’t want to have to continually snooze notifications manually. And you don’t want to have to manually turn them on or off every day, at least twice a day, to keep work stuff at bay while you’re trying to stay away.

So Basecamp 3 lets you set a notifications schedule.

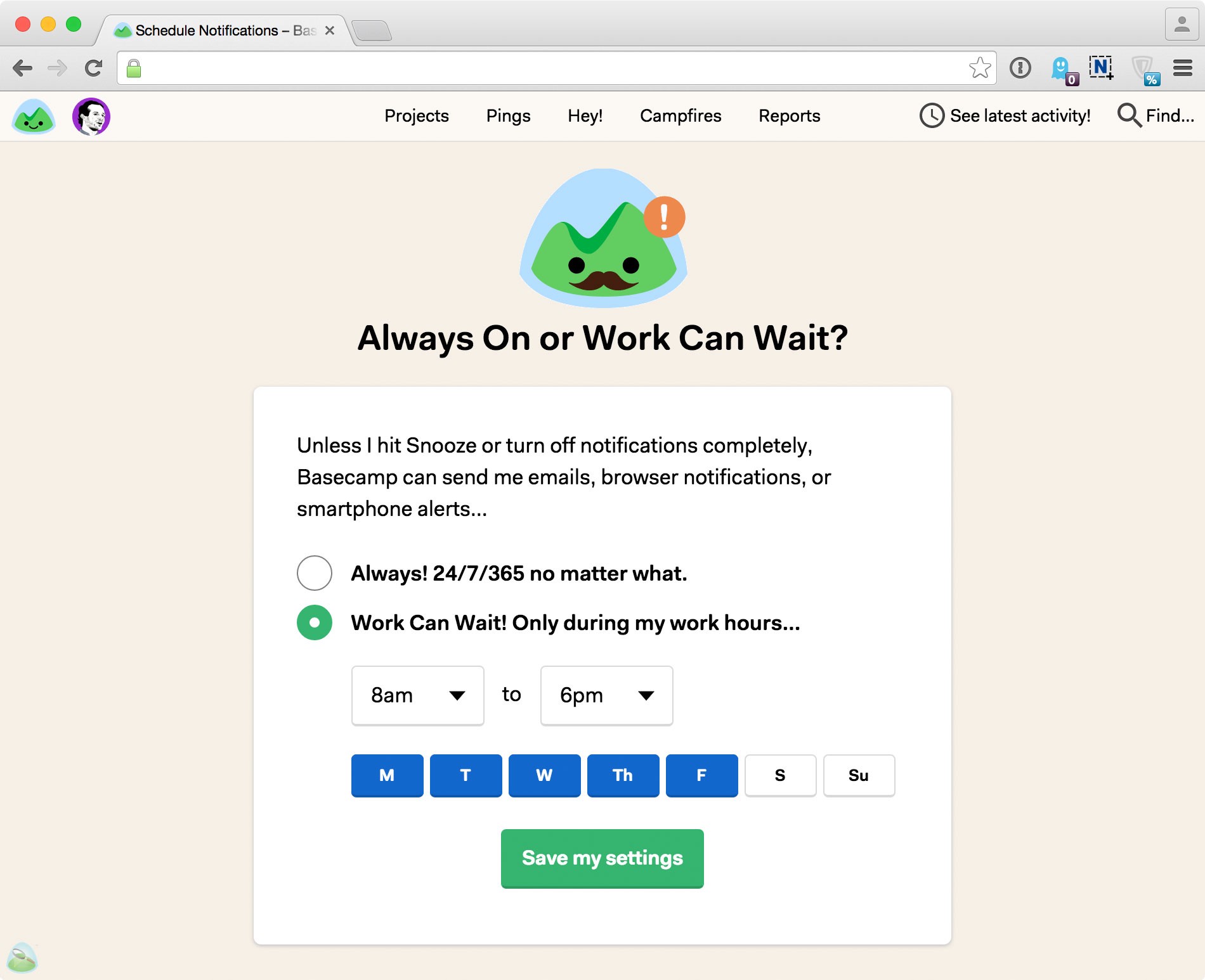

Each person in Basecamp 3 can set up their own work schedule with their own hours. You can of course choose to to receive notifications all the time, 24/7/365, no matter what. Or, you can say Work Can Wait — only send me notifications during my work hours. Then you can set the start time and end time and also mark off which days you work.

The example above are my work hours. Monday through Friday from 8am to 6pm in my time zone.

Outside of this range, Basecamp will basically “hold my calls”. Notifications will automatically be silenced until it’s work time again. Once the clock strikes 8am, notifications will start back up again. Of course at any time I can go into the web app or native apps and check my notifications myself, but that’s me making that decision rather than software throwing stuff at me when I’m going for a walk with my son on a Saturday morning.

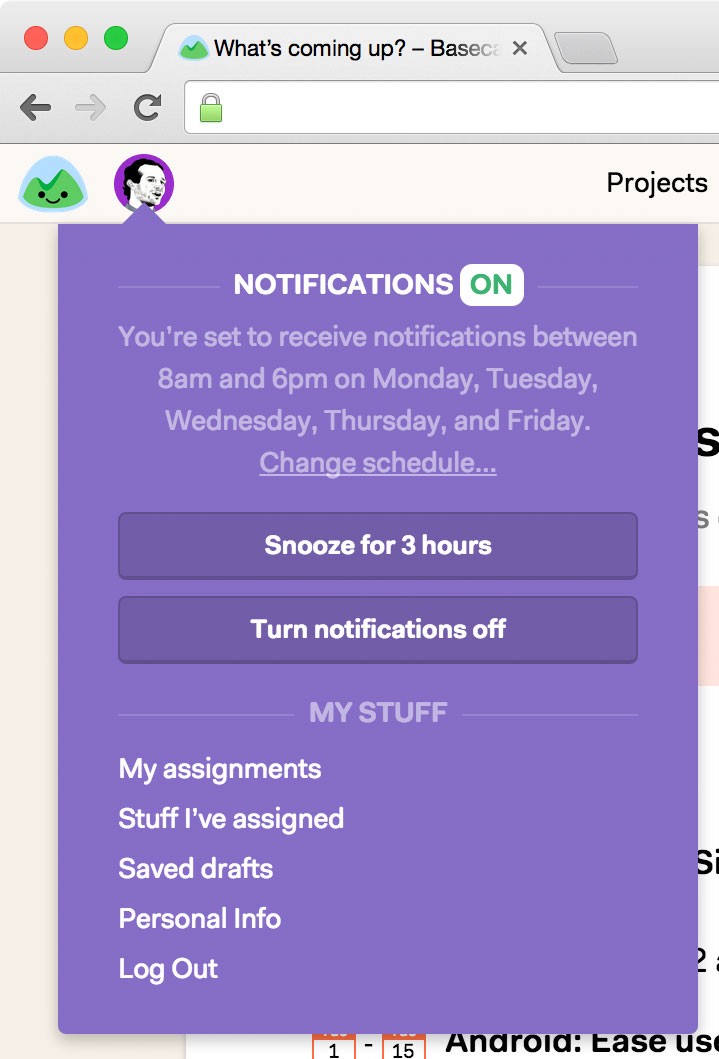

We also make it really easy to snooze notifications for a few hours, turn notifications off completely, or see/change your schedule quickly.

When you click your picture at the top of the screen you’ll see your current notifications settings. In this first example, notifications are ON because I’m on a schedule from 8am — 6pm M-F. If I want to change that schedule I can just click the “change schedule…” link and switch to always on or tweak my days/hours.

And while they are on, I can quickly snooze them for 3 hours, or turn them off completely until I turn them back on.

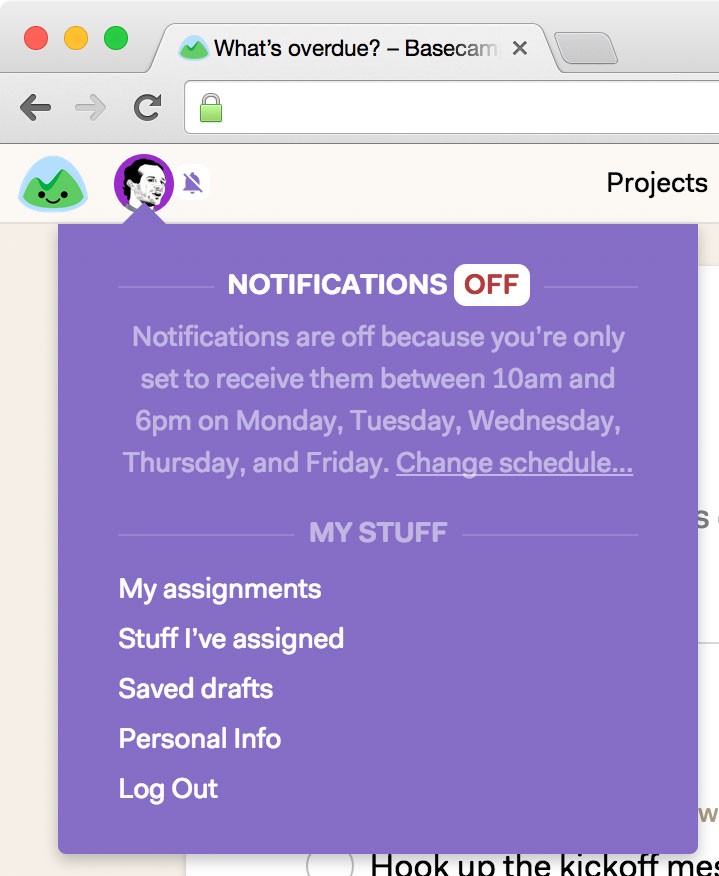

If notifications are off, it’ll tell me they are off and then it’ll tell me why. In this example they’re off because I’m set to receive them between 10am and 6pm, and it was 9:23am when I took this screenshot.

We believe Work Can Wait is an important notion. 9pm on Friday night is not work time. 6am on Wednesday morning is not work time. It may be for you, but it’s not for me. And I don’t want it to be work time for my employees either.

Every user on Basecamp 3 starts with a default work time from 8am to 6pm in their own time zone. People are free to change it, of course, but we think it’s important to encourage Work Can Wait rather than default everyone’s notifications on 24/7/365.

We hope more products offer similar abilities to shut themselves off when work is over. “You can get ahold of me about work whenever” will eventually lead to “I don’t want to work here anymore”.

Here’s to early mornings, evenings, and weekends being free from work. Work Can Wait.