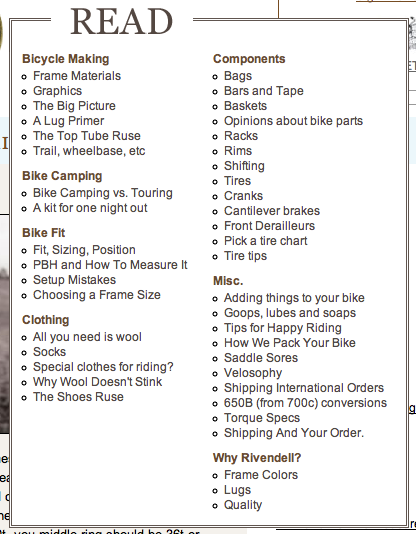

A while back, we posted about the no-nonsense, opinionated, shopping/educational content at Rivendell, a small specialty bicycle business based in San Francisco. Recently, we talked with Rivendell owner Grant Petersen to find out more about his business. (Grant also answers some reader questions in the comments.)

What custom means

When Grant Petersen was 19, he ordered a custom bamboo fly rod made by Doug Merrick of the Winston Rod Company. “I wanted red winding on the guides — ‘Like a Leonard rod,’ I said — and a cork grip shaped like a Payne rod. They were two other fancy rods,” explains Peterson. Merrick refused. “I won’t do it,” he told Petersen. “It wouldn’t be my rod, then.”

Petersen says, “I felt ashamed for having asked, but glad to have been told that. And it made me appreciate the details that made a Winston a Winston.” Decades later, Petersen points to that interaction as inspiration for how he deals with customers at Rivendell, his biking business. “I don’t want anybody to feel ashamed for asking us to drill holes in forks or make a bike with low ‘trail,’ but I’m resolved not to do it for the same reason Doug Merrick held his ground.

“To a customer, a custom frame can mean ‘I pay you money and you let me design the bike,’ but that’s not what custom means here. We’ve turned down ‘custom’ orders when it’s meant all we do is collect the money and facilitate the customer’s own design. It can be seen as not customer-friendly, but in the end it means I know that every custom has the qualities I value and a certain amount of integrity. If you stand for something and are committed to it, then you dilute it if you introduce something that’s less pure or hard-core.”

If you stand for something and are committed to it, then you dilute it if you introduce something that’s less pure or hard-core.

Opinions are mandatory

Rivendell sells the kinds of bikes and bike gear you can’t get in a normal bike shop. According to Petersen, “99 percent of the bike market — designers, buiders, distributers, retailers, buyers, and riders — are selling the wrong bikes to the wrong people for the wrong reasons.”

Strong opinions are at the heart of Rivendell’s mission. “Specs are fine, but they take two seconds, and opinions, if they’re based on experience, are more interesting. If you know about something, you have an opinion about it.

“There’s always a story behind the pure specs of something. Does it mean anything to anybody that a Nitto handlebar may be made from 2014 T6 aluminum? If you leave it at that, it doesn’t. It not only doesn’t, it’s a bad thing to just say that, because it’s really saying, ‘I read that this is true. It sounds important. I don’t know what it means. But I hope you think that I do.’ But I can add that Nitto handlebars are the strongest and safest and most rigidly tested in the world and if Nitto says it can’t make a strong enough bar that weighs less than 265g, then you can believe nobody else can.’”

Grant Petersen (photo by Martin Sundberg)

The opinionated path is one that has long appealed to Petersen. “In the ‘70s and early ‘80s, I worked at REI in Berkeley and there was a rule: No Handwritten Signs. We had a sign-making machine, and the store wanted a consistent look in all the signs. There’d be a sign for ‘Camping Books’. It was yellow-brown with dark brown letters and that’s all it said. But there was one book with the unfortunate title of ‘Pleasure Packing’ that seemed super soft-core by its title and cover, but was actually really radical inside with stuff I didn’t even know. And I thought I knew everything.

“I looked up sales on that book. Berkeley sold about 10 a year; Seattle (the only other REI at the time) sold about 20. I wrote a note about the book on a piece of cardboard, put clear packing tape over it so it wouldn’t smear, installed a grommet in the corner of it, and hung it in the book section. The first year after that we sold 215 of them. To me, it wasn’t about the sales. It was about getting the information out there.

“When I’m interested in something and want to know about it, or at least want to, or need to, get a good one — whatever it is — I want to talk to somebody who knows everything about it. Specs don’t tell me that, but the guy who sells them, or has sold them for 20 years, or the guy who repairs them — he knows. And I want to know what he does. Who doesn’t?”

The rest of the Rivendell team is encouraged to speak out too. “Everybody here has opinions,” says Petersen. “You can’t work here without them, because if you don’t have opinions, you’re just going to be a spec-reciting mannequin and no help to anybody. People want more than specs. They want specs, for sure. But they aren’t robots, so they want more than that.”

If you don’t have opinions, you’re just going to be a spec-reciting mannequin and no helpto anybody .

One thing Petersen avoids is the word “very.” He explains, “In 16 years of newsletters, catalogues, brochures, and web stuff, I have never used the word ‘very.’ It’s not a bad word. But I read once that it’s a weak word and that if you describe around it, the reader will feel the ‘very.’ And it’s more effective to have them feel it.

“Spencer here once put a new item up on the site and wrote a few lines describing it and used the V word. And I changed it and felt bad and explained to him that I wanted to keep a clean nose, that it was just a dumb obsession of mine, and don’t be mad or feel scolded. Just try to understand.”

The Roadeo from Rivendell

The Roadeo from Rivendell

Formed out of Bridgestone’s ashes

Before Rivendell, Petersen worked at Bridgestone Cycle (U.S.A.) for ten years as Marketing Director. He also had design input, wrote ads, was the media contact, and served as in-house technical guy. While there, he spearheaded Bridgestone’s attempt to bypass dealers and sell what he calls “out there gear” directly to customers via direct marketing and newsletters. When Bridgestone shut down, Petersen had developed a reputation that allowed him to start Rivendell with a built-in audience.

As for money, Petersen got by with his severance package and a little help from his friends. “I left Bridgestone with $23,500 in after-tax severence pay. I took that, cashed in some IRA money, made Rivendell an S-Corp, and sold stock at $1 a share to friends (before we made our first sale). All that combined came up to $89,000 to start the business, with me owning about 60 percent of that.

“I got some office supplies from Bridgestone, had my used Mac, and hired an outside company to put together a customized Filemaker program to run the business. I sent out a mailing with flyer and a letter saying ‘Hey, I’m in over my head, help out, let’s go!’ I hired one guy, we worked out of my garage and kept inventory in my backyard and in a 10×10 storage facility, and two years later we moved to a small warehouse.”

One thing Petersen didn’t worry about while starting up: how to get out. He says, “When you write a business plan, the last thing you address is your exit strategy. And when I started Rivendell and got a book of business plan templates, I’d never even heard the term. My reaction was, ‘What’s this stuff about getting rid of the business? I want to make a business and have a job!’”

Profit isn’t the only thing

From there, revenue began climbing. According to Petersen, sales last year were about $2.7 million dollars. Still, much of the company’s value is in its inventory. “I’d say we’re wildly successful, but don’t have wild profits to show for it. We’re established, more people know about us, and we have loyal customer who tell their friends about us. And, especially important to me, we employ about 13 terrific people, and I think every one of them would tell you this is the best job they’ve ever had.

“I think, if your main reason for being in business is to maximize profitability, you must hate the work itself. We recently got in some custom-made-for-us tiddly winks made out of tagua nuts. They cost us $13 a set (of 25) and we sell them for $20 and donate the difference to charity. A profit-first business could never do that. It would miss out on the fun.

I think, if your main reason for being in business is to maximize profitability, you must hate the work itself.

“It sounds stupid, but little unprofitable projects that aren’t huge time-resource sucks can pay their way without being profitable. Because they add to the fun, the make the business more interesting, and sometimes when you’re working on several projects that take a year or more to mature, you need quickies like this to keep you going. I value sustainability over that kind of profitability. I really want to be here as a business, because employing people is more important to me than super profitability.”

That attitude helps to explain the company’s charitable streak too. It raised over $50,000 for Smile Train last year and gives money to other charities too. Petersen says, “Everybody here knows he or she can give a bike away to somebody who, for whatever reason, clearly warrants a free bike and can’t afford it. They’re expensive bikes, too.”

Running hot and cold

One thing employees must deal with is a workplace that runs hot and cold. Literally. “We have six continguous 900-square foot units in an uninsulated building intended for car repair businesses,” explains Petersen. “Our record cold morning was 38 degrees — cold enough to solidify the olive oil. Our record heat was 111F, and I’m talking about in the work area, not outside. At this moment, I’m freezing. Bad planning, clothes-wise, today.”

Employees know what they’re in store for when they start. Petersen says, “Every new hire gets told the story before they commit, and nobody’s left because of the weather. You have your main task, and you can grow it as you like, or take on other work as you’re interested in it. Everybody works really hard, and that feeds on itself. We’re all friends, and it makes work fun.

Employees know what they’re in store for when they start. Petersen says, “Every new hire gets told the story before they commit, and nobody’s left because of the weather. You have your main task, and you can grow it as you like, or take on other work as you’re interested in it. Everybody works really hard, and that feeds on itself. We’re all friends, and it makes work fun.

“We spend $20,000 a year on employee lunches, because even though everyone is free to take the hour the law allows, it’s rare that anybody does that. There’s great food around here, and anybody who leaves and gets another job may make more money there, but their lunches will be way worse.

“Also, everybody here knows they have the power to do anything they want for any customer. They know to always take the customer’s side, and that the worst thing they can do is take the company’s side in a quibble involving service or money or anything else.

“I want to sell it to the employees within ten years, continue to have some involvement, but see them continue the direction and increase our influence.”

Pick something the big guys don’t care about

Petersen’s advice for others who want to get a business off the ground: “Don’t copy anybody else. So many businesses look at the trends and follow the leaders hoping they can be a leader, or can at least live in the wake of the leader. There’s a cliche that, ‘If it’s a good idea, it’s too late,’ and I go along with that. Pick something the giants in that industry don’t care about, or something they can’t get into without shooting themselves in the foot.

“For instance, we do hand-made lugged steel bikes with decidedly anti-racerlike qualities to them. They’re comfortable, strong, versatile, and will last 20 to 50 years. We hate carbon fiber, and we can say that. Now, if Trek or Giant or somebody catches wind that a certain segment of the bike market is getting into lugged steel bikes, they still won’t be attracted to it, for two reasons. One, it’s so small. That shouldn’t matter to a new business, but it limits the appeal to an established leader. And two, we can position lugged steel bikes as the better-safer-smarter alternative to carbon, but they can’t, because carbon’s their bread and butter. It would be like a smoke shop selling anti-oxidants or jumpropes. It can’t work.

“So for anybody starting up, I’d say don’t copy. Find a weakness in the giant, something they can’t cover. And make it important enough to you that even if it doesn’t work out great at first, you can at least know it matters enough to do. And do it in a way that allows you a large measure of self-respect. The worst thing I can imagine, as a business owner, is doing something I don’t believe in and having no customers to boot.

“Do something that matters enough to you that you can honestly tell yourself that if business is bad, if nobody’s buying, it’s because they’re misinformed, backwards, or just dumb. You have to have a purpose that keeps you committed, independent of success.”

The Rivendell Bikes “classroom.”

This is part of our “Bootstrapped, Profitable, & Proud” series which profiles companies that have over one million dollars in revenues, didn’t take VC, and are profitable.

Related: Interview with Grant Petersen of Rivendell Bicycle Works [Push Button For]

Bjorn

on 10 Feb 11I don’t have a Rivendell bike, but I’ve read every page of their website. Smart, pragmatic advice for a recreational or commuting cyclist. An ounce of classic bike wisdom has saved me a ton of money.

Shaun

on 10 Feb 11Hey Grant! I was on the original mailing list, to which you sent out the first Rivendell mailing (was a BOB member). To be honest, when I ready your mailing, I thought you were off your rocker. I have since become a loyal customer and an very appreciative of your bicycle designs (I’ve bought two of your bikes). What are some of the most important things you’ve learned along the way about bike design and have your fundamental principles of bike design changed over the years? Thanks for taking the time.

Steve

on 10 Feb 11Hey Grant, I have a quick question. I’m a college student in Monterey and I would like to be able to commute 100% by bike. I ride a Surly cross-check with Albatross bars and Shwalbe marathons from Rivendell of course. I was wondering if you had a favorite Rack/Bag combo, or if you could think of a good one for a student with 3 classes of books (Riv. bags and Riv. racks). Keep up the good work! Steve p.s. Primal Blueprint changed my life -Thanks!

rkt88edmo

on 10 Feb 11Hi Grant,

Will you consider a non-bike headbadge to sell? I managed to get one of the keychains since ya gotta own a Riv to get a Riv headbadge, but I think a standalone headbadge would be a great piece of schwag.

Anyways, I’m local and have come by and bought accessories, I don’t know if I’ll ever come around to wanting a rivbike but hopefully I’ll join you all for a ride someday.

Brian in Kansas

on 10 Feb 11Grant,

Thanks for the interview.

I have two questions – will Rivendell ever produce a commuter/city bike?

Are there any plans to bring out an updated version of the fabled Bridgestone XO-1?

Love your stuff. Keep on with the mission.

Regards, Brian in Kansas.

rkt88edmo

on 10 Feb 11Could even be a RivSmile fundraiser. I think headbadges would sell like hotcakes to Rivfanboys.

GregT

on 10 Feb 11This is by far the most inspiring BP&P so far, IMHO. It’s nice it’s not about software! This guy sounds kind of like Howard Roark, and I mean that in a good way.

Still, I think if I asked them to make some little change and they refused on principle, I’d be choked ;)

Chris

on 10 Feb 11Grant,

Thanks! Keep fighting the good fight.

rkt88edmo

on 10 Feb 11@Brian – I think every Rivendell is a commuter city bike – just slap on fenders/rack/bag as needed (which they stock) and lights and you’re set. Is there a particular quality you think the bikes are missing to fit in that category?

Bob Baxter

on 10 Feb 11I may have gotten a bit testy while waiting for the Betty Foy to show up, but after almost 2000 miles it has become #1 in my stable of 8—soon to be 9 with the addition of an ANT Basket Bike. I keep saying that I won’t buy another bicycle but if you come out with something that turns my crank, who knows? But you’d better hurry as I’m only 17 years off the century mark.

Ron in Kalamazoo

on 10 Feb 11Grant, just wanted to say thank you for making me feel good about being a sandal wearing old guy on a fat-tired steel bike. Hopefully one day I can afford one of your beautiful designs.

Brian in Kansas

on 10 Feb 11Grant,

I was thinking of an internal gear hub drive bike with an enclosed drivetrain or a an internal gear hub with a belt drive.

-Brian

Esteban

on 10 Feb 11A pleasure to read, and a thwack to the side of the head of “race to the bottom” business models.

Tom

on 10 Feb 11Hi, Grant: Thanks for waiting on me after I showed up at Riv HQ last April early on a Saturday morning. I put the bits I purchased to good use on a bike for my nephew.

Any hints on groundbreaking models in the works at Riv HQ?

Chris (again)

on 10 Feb 11Will the Atlantis work with a 650b wheel? Thanks!

Grant

on 10 Feb 11SHAUN ASKED : What are some of the most important things you’ve learned along the way about bike design and have your fundamental principles of bike design changed over the years?

(I forgot to fill in my name before. I’m Grant) That you ride the bike, not the frame, and that means your contact point triangle (saddle-bars-pedals) is more important than the frame’s numbers/geometry. You need to start off with the geometry- sizing and all -but the frame’s just a launching point for the saddle-bars-pedals, and the “right” geometry is the one that allows you to get your S-B-P in the right place. Also, I used to believe short chainstays made a bike faster, and now I know that’s not how it works. And when I look at a bike now, I look for clearances around the tire and brakes, because that tells me / you / everybody what kind of tire will fit, and THAT determines what the bike is good for. In the old days, I glossed over that stuff. G

AllanFolz

on 10 Feb 11Grant, this one is kind of a classic but nonetheless… what question about bikes never gets asked, but probably should.

Grant

on 10 Feb 11STEVE ASKED: was wondering if you had a favorite Rack/Bag combo, or if you could think of a good one for a student with 3 classes of books (Riv. bags and Riv. racks).

Too many ways to do it, but I’m assuming you’re trying to spend as little as possible (student and all), and I appreciate you limiting it to Riv stuff, but here: Get a rear rack for $50 or less somewhere (won’t be here). Delta Cycle has some cheap and good. Then get (from us, maybe) a big Wald basket for $20, and a net for $12 or so. Zip-tie the basket onto the rack using the thickest blackest zip-ties you can find, and quintuple-wrap each connection. You can put your daypack-of-books in the basket, and not have to leave a pricey bag on the bike for another student to steal. G

Lovely Bicycle!

on 10 Feb 11Dear Grant,

I am a huge fan of Rivendell and own a Sam Hillborne, which I love beyond words. But I was surprised and disappointed to see the new design of the Bombadil, particularly this junction, as well as by the equivalent junction on the Betty Foy. To me, incorporating such elements into your designs contradicts the reputation for commitment to lugwork that you’ve worked so hard to build up. Is there any chance of a mixte in future that has a properly lugged junction, like your Glorius once did?

Grant

on 10 Feb 11RKT88edmo said: Will you consider a non-bike headbadge to sell? I managed to get one of the keychains since ya gotta own a Riv to get a Riv headbadge, but I think a standalone headbadge would be a great piece of schwag.

Well, if it’s curved to fit a head tube it’s a headbadge, and we won’t sell those, because scoundrels will get ahold of them and put them on bad bikes, and then strangers will think it’s ours..but if you’re talking about flat versions, like coins, we’ve done that with the AHH and Hunqapillar, and I think it’s a good idea to do with all our badges. Thanks. Will do. It takes a while, but we’ll eventually have a lot of those. They make good refrigerator magnets, and we can get some bolo-tie fittings and braided kangaroo. No kidding a bit. G

Lovely Bicycle!

on 10 Feb 11Oops, my Bombadil link did not go to the right place. Here is the link I meant.

Grant

on 10 Feb 11BRIAN the KANSAN asked: I have two questions – will Rivendell ever produce a commuter/city bike?

Are there any plans to bring out an updated version of the fabled Bridgestone XO-1?

1. We’re working on it now, but seriously, this is between you and I. Since it’ll be a Riv, it has to be lugged and steel; and as a commuter bike, it should be tough and affordable. So we plan to use cheap good tubing (all CrMo), and go down & dirty in the details when fancying them up wouldn’t add function; and then sell it primered but not painted, the idea being that you could rattle-can it yourself, make it look cheap and ugly and already stolen, to scare off dope addict thieves looking for a quick flip for their next fix. The lugging of it limits the lowness of the price, but we are working on it. Shorter answer: Yes.

2. The XO-1 was a neat bike, but it was designed and made under constraints I don’t have now. I was working for Bridgestone, and now I work for me, and there’s a difference there. So, the Atlantis is basically where the XO-1 would have gone/should have been, without those constraints. Neat bike, super for its time, but so was the Apple IIc. Look at the Atlantis, Hunqa, Sam….they’ve got it beat. G

Grant

on 10 Feb 11KansanBrian clarifies his question asking are we gunna do a city bike: I was thinking of an internal gear hub drive bike with an enclosed drivetrain or a an internal gear hub with a belt drive.

Dang, I spilled all those beans for nothing? OK. No on the internal/belt. They have their place, I believe in them to a point, I know the deal…but I’m not smart enough about them to feel good doing them. Anything we do has to be something I know inside and out, and I’m not there with internal gears or belts. Internals, I think--though-are not entirely maintenance-free, which is what I think a lot of the appeal IS; and they’re harder to maintain when you need to maintain ‘em. Belts need a frame you can separate. I’d love to dominate the world, but for now I’m happy leaving belts and internals to people who are smarter than I am.

Mark Shaw

on 10 Feb 11Nice report on Rivendell. They are doing it right. Building right and actually caring about the opinions they are receiving. But as a CRM business owner, that’s easier said than done. I want everyone to feel heard, but I just don’t find the capacity to put it all into practice. That’s my dilemma.

Bill

on 10 Feb 11It has been interesting watching the evolution of frame production in the last few years from Japan to Taiwan and now (for some, anyway) back to the US. Do you see this as a trend back toward US production of some things, or just another swing in the global market?

Bag production has similarly moved around; is that the same supply forces at work, or more a change of aesthetic?

FWIW, the source country isn’t as important to me as a fair trade, and i appreciate that Rivendell (you) is (are) open about their sourcing and partners in these projects.

AllanFolz

on 10 Feb 11And if we’re allowed two questions :-) ... Grant, do you think the healthy resale market for Riv goods helps or hurts Riv as a business. Well, I guess no effect is an option too. Never let it is be said I traffic in logic fallacies.

Grant

on 10 Feb 11TOM ASKED: Any hints on groundbreaking models in the works at Riv HQ?

OK, now the earlier answer about the cheap bike isn’t entirely wasted. That’s the only one in the works. We’ve got most of the other bases covered, I think, and it’s nice to not have to create new models out of desperation. We basically have

Tourish bike: Atlantis $$$ SuperTough bikes: Hunqapiller $$ and Bombadil $$$$ Roadish with Trail options: Sam $ and Homer: $$$ Girly and easy standover: Betty and Gomez $ SpeedFiend: Roadeo $$$ CUSTOM: $$$$$$

G

Grant

on 10 Feb 11ALLAN ASKED TWO: what question about bikes never gets asked, but probably should. and do you think the healthy resale market for Riv goods helps or hurts Riv as a business.

1. I think every buyer should ask these questions: —what’s the biggest tire this bike will take? —will it fit a fender? —can I get the handlebar higher than the saddle?

But those would be mean questions in most bike shops. They’d think you were a jerk for asking. They wouldn’t have the answers, or the answers would be No NO No, and then the awkwardness. So I’d like bike makers to supply that info on hang tags. Those are super important questions, and as long as nobody’s asking, the makers have no reason to make bikes that way (I’d say the good way; they’d say, “the old-fashioned dumb slow way”)

2. (Resale hurting new sales?) Not too much, but it always hurts when I see one of our bikes for sale. It means either somebody got a divorce, lost a job, or the better but still lousy explanation: didn’t like the bike enough to keep it. And if THAT’s the reason, what went wrong? We are so careful. We know how to fit sight unseen, with simple measurements. We do it all the time,and it works so well. Far more common is for somebody to buy one from us, then another, and maybe another after that. Those are happy, not because of the $, but it says we’re doing things right. Whenever i hear of a second-hand or for sale Riv bike, it hurts.

Tim

on 10 Feb 11Hey guys a guy at work here in Oz, Matt KG flew stateside and visited you guys. He was raving about the place and how you lent him a bike to try – ALL DAY.

It’s actions (and implied trust) that win consumers for life. Clearly you guys are about the love of bikes.

Tim M

PS when are you doing a carbon racer? PPS Just kidding.

Grant

on 10 Feb 11BILL ASKED 2TOO: watching the evolution of frame production in the last few years from Japan to Taiwan and now (for some, anyway) back to the US. Do you see this as a trend back toward US production of some things, or just another swing in the global market?

Bag production has similarly moved around; is that the same supply forces at work, or more a change of aesthetic?

Trend back to US—-I don’t know about that, but US-made stuff is always our first choice, and I’ve known and liked and worked with Waterford (makes many of our bikes) for 16 years, and they’re easy. They speak midwestern a little, but it’s fairly easy to interpret, and so communication is easy, and we can order fewer at a time and get ‘em faster. When we get bikes from Taiwan or Japan, it’s high minimums and longer lead times, and a whomping bill to pay when the arrive. Our bags have been made in England and the US,and we’re now on our 4th and best supplier in the US. It’s nice when you go to a bagmaker with a design and they tell you, “No, don’t do it that way. That’s dumb. Look, here’s a much better way.” That’s how it is now, and when we first got connected, their quality standard was higher than ours—-another good feeling. We’ve learned a lot and are settling in, and I hope Waterbury (not to be confused with WaterFORD) continues with us for a long time.Matt

on 10 Feb 11I was able to visit Rivendell at the end of a long tour last summer, and everyone there was very easy to talk to. They even treated me to lunch. It was hot that day. If you go there, no matter how lost you are, do not try to ride your bike on Ygnacio road at rush hour…

rkt88edmo

on 10 Feb 11If I recall correctly, you’ve recently worked with two other SF area bike designers SOMA & Xtracycle. How different is it working your concepts into their products, seems halfway between Bridgestone and Riv? Any short anecdotes from either of those processes?

Grant

on 10 Feb 11rkt88edmo asked what it’s like working with other companies (I design bikes for some other sometimes, or help with geometry problems, or stuff) How different is it working your concepts into their products, seems halfway between Bridgestone and Riv? Any short anecdotes from either of those processes?

XtraCycle was having some steering quirks on a bike, so I recommended specific changes, and it seems to have helped. It couldn’t not have, but I can say I’ve steered the latest model. It was easy to work that out.

A few years ago I was asked to design a bike for one of the three biggies, a kind of bike we do (good road, good trail, good carrying), and I came up with good numbers and details, a good plan, but they didn’t do any of it. They did it the way they’d have done it if I weren’t even involved, the predicatble way, the way a high school kid who was into bikes and was familiar with common frame geometry thinking would have done it to make it fit right in. Then on the site they credited me with being part of the “think tank” or something, which I didn’t like because they didn’t take even one of my ideas, and yet still gave me credit. I don’t want credit. I’d rather they’d done it my way and kept me out of it, than ignored my design and given me credit. So…dat wadn’t satisfying. (I didn’t take payment for this, I was happy to do it, the owner’s a friend). I got a bike out of it, but I wasn’t bikeless before, so…

It’s been good with SOMA. They asked me to design a road bike for them, and based on my experienced with the other company, I was more particular about how it was going to go, trying to avoid another one of those.

All I did on it was the geometry and clearances and I know that’s not minor; I’m just saying I didn’t name it or pick the color or certain other details that aren’t strictly geometry or clearances. In the process of it, I learned something I’d only had a suspicion of before, but now it was slammed home. It’s something that I think Nobody who designs bikes knows. I just don’t think they do. It’s a subtle, quiet, secret relationship related to seat stay angle and brake reach, and now it seems obvious, but it’s not OUT THERE in the world, and I really liked learning it. I know nobody reading this would care what that was, so I won’t go into it, but for me it was neat. Anyway, the SOMA bikes will be around in a few months,and any dealer can get them, and it’ll be neat to see how they do. We (RIV) get $6whole for each bike that sells, so….at the end of a year we maybe up about $2,000, minus the 100 hours or so I’ve put into it!

Jax

on 11 Feb 11Oh please make that city bike your talking about asap pretty please. Any dates? 2012 or later or will we see it in 2011?

I live in the EastBay and would love a steel frame with my nitto albatross, brooks, nitto crystal, Marks rack, dropdirt, and portugal cork grips. (All orders from you) But I bart/bike to the tenderloin everyday with my bike. Thats the only reason why I havent bought a SH frame yet. Im just to scared to take a SH to the “loin and pill hill” to lock up everyday. I have even thought of buying one and stripping the head badge and paint but its to beautiful. If you did sell one I would do more then just a rattlecan spray paint to it but not the level of the SH or others.

thanks

Ron

on 11 Feb 11Hi, there, Grant. I’m saving up for a Sam, and will place an order this year, but on the topic of multiple bikes, what two (or three) bikes from Riv do you see people that buy multiples lean toward? Or maybe it’s an “I’ve got one, now let’s get one for my significant other/kids, etc” kinda thing.

Fred Zeppelin

on 11 Feb 11Grant, I was under the impression that the drop out thickness:bottle boss location ratio was the secret that the old Italian master framebuilders really had nailed, but then everyone went to two sets of bottle bosses and the formula was lost.

How does your seatstay to brake reach relationship fit in to all this?

Rick H

on 11 Feb 11Grant

I will own a Riv some day. Is it possible to visit your shop prior to purchase to talk about your bikes

Rick from St. Louis

Gooseneck

on 11 Feb 11Grant, How can it be that Jan Heine/BQ so strongly advocates low trail these days, and you/Riv seem so strongly all about the mid to high trail?

Where is there a place for low trail geometry (if at all) in your opinion? I don’t want to force you to put anybody down or call someone a liar. I know it’s a tedious and contentious subject, but it’s a topical one that’s been nagging me. I’m sure others have the same question – any light you can shine on this would be greatly appreciated.

+1 on the seatstay/brake reach relationship. That was a bit of a teaser on your part, I think.

Thanks! Chris

Sean

on 11 Feb 11On the way home, I was thinking about this post and your company. Hope it’s not too late to ask. :) How do you get off the ground when you have a very expensive product that people don’t know about?

grant

on 11 Feb 11RON ASKED: what two (or three) bikes from Riv do you see people that buy multiples lean toward?

I wish I could be definitively specific, but there are lots of common combinations. Usually a fattish tire bike and a slenderer tire bike, some like (first bike bought on left):Atlantis – Homer Atlantis – Sam Atlantis – Roadeo

or Homer – Hunqa Custom roadish bike – Hunqa

Although one fellow has 3 Bombadils.

G

123 neon signs

on 11 Feb 11I’m so happy to see that biking is being advocated so well. It is such a huge part of travel in Europe, and the benefits are so awesome, that there is no reason that we should be getting in the car to go to the store. Weight loss, environment, fewer cars on the road… Benefits are nearly endless.

grant

on 11 Feb 11FRED commented: I was under the impression that the drop out thickness:bottle boss location ratio was the secret that the old Italian master framebuilders really had nailed, but then everyone went to two sets of bottle bosses and the formula was lost.

Hmm . . . I’ve never heard of that before. Forged dropouts are thinner than cast ones, but lots of the frames built by the old masters with 7mm forged rear dropouts broke. Rear dropouts can break, even when all seems to be well. As long as the inside-to-inside dimension fits the hub, and the dropout allows the skewers to be engaged fully, then it’s all fine by me. The water bottle placement thing is a—well, things change over time, usually for a reason. I’d suggest anybody besides Fred who’s still reading this, go away now and spare yourself, because it’s going to get nitty gritty and not that interesting, but Fred asked, and I agreed to answer, so… In the OLD days bikes carried one bottle on the down tube, and the pump fit in front of the seat tube between the top tube and bb. Then the bosses were lower-middle of the down tube, low enough to be out of the way of the decal, and about where your hand falls naturally, although I doubt they gave much thought to it. When two bottle became common, the second one had to go onto the seat tube, which pushed the pump to under the down tube. The classiest way, if you have to assign a class score, is to position the two bottles so the lower edge of the bottles almost touch one another. It satisfies the symmetricists, and there are a lot of them out there.

But when big bottles came around, that location didn’t always work with small frames, because the bottle could knock on the pump when you pulled it out. So lowering the seat tube bottle bosses solved that, at the cost of symmetry (a small cost, I think, but I’m slobby about some things). On our frames, we get back some of the symmetry by making the bottle bosses equidistant from the front derailer clamp (the spec is 11cm above the center of the bb) It’s all hairsplitting at this point--I mean, you can’t make a fantastic case for bottle-bottoms nearly kissing, and so when I say the lower bottles keep the weight of the water lower on the bike (assuming that’s better than carrying weight higher), you can’t -- I don’t mean YOU, Fred, I mean ANYBODY who argues for symmetry can’t make too much fun of this, since it may be a small difference, but at least it weights function over pleasing somebody who’d looking at the bike from afar.

Some bikes have third bottles, and they always go under the downtube near the bottom bracket. You shouldn’t drink out of the third bottle; if you’ve emptied two and need that one, it’s time to stop and rotate bottles. Let’s say you’ve start a ride with three full bottles, because it’s hot. Because it’s hot, you aren’t expecting rain, and this bike doesn’t have fenders. You empty your two uppper bottles and reach for the third. To pull it out you pull it up and forward, toward the front tire. As you’re leaned over and tired, you grab the third bottle, and they’re often a tight fit, so you pull hard to get it out, and as it comes out, it hits the front tire and gets wedged between it and the downtube, and gets sucked in behind the fork, and with one hand on the handlebar, you do an endo. I see this happen at least once a month (lie, there). I have heard of it happening, and I bet it’s happened a lot without me hearing of it…so that’s why you shouldn’t drink from the underside bottle. To make sure you don’t, put a strap around it.

G

Nick

on 11 Feb 11Oh man, I want a Riv but it just has to have an IGH. I have to pay off 2 college educations first. If I get them paid off before you change your mind then I guess I’ll own a bike with derailers. But if you change your mind first, thats what I’m hoping for.

Matt

on 11 Feb 11One of the unique things about Rivendell and its history (including Bridgestone) is the use of genuine/heartfelt treatise, to get the word out, and get people’s gears turning about certain aspects of riding bikes. The Rivendell Reader, for instance, is a huge part of what makes the company interesting, unique, and good, IMHO. In fact, this seems to have spawned a renewal of informative publications related to bicycles, such as Bicycle Quarterly and Bicycle Times, etc (I know Rivendell and Bicycle Quarterly do not agree necessarily on some things, like geometry, but I think they have much more in common than not!). Grant also sells non-bicycle-related books that he thinks are worthwhile, such as the Primal Blueprint, and the Long Walk. Again, I’m pretty sure this is entirely unique among bicycle companies. Grant, if you are reading this, my question is this: I have heard rumors that you may be writing a book at some point, sort of a compendium of years of experience/philosophy/observations. Is there any truth to this? It would be loong overdue I think, and needless to say I (and a lot of other folks) would be excited to read it (and it’s sequel, of course!) Cheers and thanks for all the informative replies you’ve already given above.

Jim Edgar

on 11 Feb 11Grant, as always, thanks for having taken the time to develop opinions, and sticking to them.

Rivendell is a gem, hardened by pressure, glorious to behld.

Thanks!

- Jim / Cyclofiend

grant

on 11 Feb 11GOOSENECK ASKED: Where is there a place for low trail geometry (if at all) in your opinion? I don’t want to force you to put anybody down or call someone a liar. I know it’s a tedious and contentious subject, but it’s a topical one that’s been nagging me. I’m sure others have the same question – any light you can shine on this would be greatly appreciated.

Jan Heine knows a lot about bikes, and is a friend of mine, and you don’t have to worry about putting me in an awkward position, calling anybody a liar—-nothing like that. PETA alert, though: There’s more than one way to skin a cat, and there is a wide ranger of handling qualities that one can get used to and even come to prefer. Jan likes less trail than I do, and there’s not much more to it than that. WHen I get on my bike, I pedal it away, swoop around, ride it all over, and think: Do I want it to behave any differently? And if the answer is No, then I leave it alone and don’t worry about the numbers. Trail is not THE determining influence on handling; it is one of many, and most bikes, over the years, have settled into trail figures in the high 50s to low 60s. To make trail an issue and to be suspicious of either low-trail (based on the minority probably being wrong) or norm trail (based on the majority usually being dumb and wrong) misses the point that you adapt to what you got. I find our bikes are easy to control even in conditions that scuttlebutt says should favor low-trail bikes. But maybe that’s just what I’m used to….but what we’re used to becomes our reality. How’s that for a non-answer? G

grant

on 11 Feb 11Gooseneck also said: +1 on the seatstay/brake reach relationship. That was a bit of a teaser on your part, I think.

I would’ve answered this along with the other, but I coudn’t select separate paragraphs, for some reason. The relationship is alluded to in an earlier post, and Gooseneck was right about it being a tease. But it’s too complicated to explain in words, or I’m not good enough with them to do it, or something like that. I’ll try, but won’t answer any follow-up questions—-which I’d read as proof that I shouldn’t have tried in the first place.

When you design a bike and you’re figuring out where to put the brake bridge (on a bike with sidepulls), the consideration is: What kind of brake reach do you want? And that should be determined by the clearances you need for tires and fenders. Let’s say the bike has a 650B wheel, which as a rim diameter of 584mm (so, a radius of 292mm). That 292mm is the hub axle to rim distance (basically, for now…). So, if I know from experience that a 33mm tire plus fender needs 55mm of brake reach, I add 55 to the 292 and come up with 357mm as the axle-to-brake hole distance. So far this is super simple (although, I’d say, largely unknown in the bike designing world, or ignored, based on the wacky bridge locations out there). But that bridge location will give more clearance on a bigger bike and less on a smaller one. On a smaller bike, the angle of the seat stays is lower, so--this is the secret vile magic that happens - the rim falls away from the brake pads faster on the back side of the brake, and climbs steeper on the front side. So even if you set the bridge for 55 reach, on a 47cm frame (for instance), the pads won’t reach the rim, and the tire will fill up the brake too much to allow a fender to fit.

So, on the SOMA frames, I had to increase the brake reach to 62mm or so, to get the same clearances that could be had on the bigger frames with only 55mm of brake reach. The bridges had to be raised.

I really, really doubt that many bike designers know this. They’re too into other things (their Facebook page, weekend plans, whatever) to be distracted by technical matters such as this. That is a mean guess. I’m sure some do know it. (That’s a lie.)

grant

on 11 Feb 11SEAN ASKED: n the way home, I was thinking about this post and your company. Hope it’s not too late to ask. :) How do you get off the ground when you have a very expensive product that people don’t know about?

I’m not Tom Peters or Mort Drucker or any of those guys, but I can answer in my case and offer some general suggestions or something. In my case, I’d started something called the Bridgestone Owners Bunch, when I was at Bstone. We had lots of cool stuff that dealers weren’t buying, so rather than sell it at a major loss with net 120 day terms and ultimately get stiffed by half of them, we figured it would be better to sell direct to end-users, collect full pop up front, and actually make money doing that. You had to join BOB, and it cost $15. We got 3900 members, and when I left Bstone, I was given the mailing list to start RIV. The first year I got 1300 conversions, and it’s grown from there. Up to that point I was semi-known in the bike world, I had a good reputation, and that made it easier. But really, it was the list that made it happen.

That was pre-net, though. At least, I wasn’t on it. These days things could happen more easily, but you still need to have something that makes sense to people you hope will be customers.

I’d say anybody starting a business should read these super-easy-to-read books:

ReWork (a 37signals publication) Focus (either by Ries or Trout, I forget which) Differentiate or Die (Trout)

Also, if I can start swearing this late in the game, learn how to write straight and not bullshit. You will be judged by your writing, and people who don’t know how smart you are will think you’re an idiot and won’t trust you if you misplace an apostrophe, or use the wrong kind of their. Most good writing is just avoiding mistakes and being yourself, but for a new business, it’s really important. I wish I could write as well as the 37signals guys who wrote ReWork. That is my model.

grant

on 11 Feb 11Matt asked: my question is this: I have heard rumors that you may be writing a book at some point, sort of a compendium of years of experience/philosophy/observations. Is there any truth to this?

I am, but I’ve been doing it largely in secret, for many reasons. One, if the publisher rejects it (I already have a publisher, Workman Publications), then I can retreat without public humiiation. Two, I am already famously slow with getting our business pub (the Rivendell Reader) out, and I don’t want people to think it’s because I’m booking. It’s not; I’m just slow at it. I work on the book at home, at night, on weekends. At one point the book was scheduled to be published in Fall of 2010, but the book at that time had grown in scope too much…it seemed like it was Grant Petersen’s Big BOring Book of Bicycling, and I was writing about stuff that doesn’t mean a lot to me——recumbents, folders, how-to-do-stuff that doesn’t need doing. The publisher told me, “There’s a book in here, somewhere,” which stung really hard, and but got me to stop that book right there and restart and write the book I wanted to write. The new date is Spring 2012, about a year from now, and two days ago I sent in my final files. I check my email every day hoping to find a note from my editor saying, “Grant, this is terrific! Good job! EXACTLY what we’d hoped for!” but my editor has other things on his plate, too so I have to wait. We have do agree on certain things about the book, too. I want it to be sort of an UnRacer’s Guide to bikes and riding, which is to say, a way to look at gear and riding that isn’t so racing-centric, racer-fawning. I think the pub would like it to be more general and happy. We’ll see how it goes.

Leslie

on 11 Feb 11Excellent read for a Friday coffee break!

Have to admit that I enjoy learning about the nuances, the “fiddlin’ ” things that go into the thought process like bottle-holder mounts and bridges, things I hadn’t ever thought about, but appreciate the end results.

I never even thought about someone trying to pull a bottle out of the 3rd mount, I would have thought getting to that one would occur during a momentary riding break, to swap. I used it more as a spare, in case someone else didn’t have a mount, to carry one for them.

I’ll second Matt’s comments, I enjoy reading through your thoughts and musings, and look forward to a book on Grant’s perspectives.

I agree, a lightish-heavish combo seems ideal (Ram-Bomb).

As I read this, I see that most of this is towards design aspects, but my current pondering quandary is in regards to handlebar selection. Any thoughts on: “dirt-drops”/woodchippers? I’ve been thinking of drop bars on a Bombadil, as a possible alternate to Bullmoose, for a rails-to-trails rider that can pull touring duty. I have big Noodles on a Ram, and started to think that I wanted something with more splay on the drops, like the woodchippers, but I like Nitto… the top of the Rando bars from them seem that they may be narrow if I’m used to a Noodle. Just going with the Bullmoose instead would simplify the process, but I like the multiple positions a drop offers. (Why not Noodles again? Just trying to differentiate between the bikes more…) Any thoughts?

Grant

on 11 Feb 11Hi Leslie, Lots of people like the super flare of some drop bars, and whatever you like is what you should get. I find the slanted brake lever on superflared bars feel funny to me - either keep them more or less vertical, or lay ‘em down flat like a Moustache H’bar does. The Bullmoose bar is great, though. It’s not purely a one-position bar, either. You can grab the forward center bar. ALso, I think that when the main position is high enough and comfy enough, you don’t need to keep searching around. Most searchers are riding drop bars in the wrong place (too low, usually), and they’re loading their hands too much, so they need to constant go from tops to hoods to ramps, and none of it’s good. I’d put Albatross bars on the Hunqa…or BM. Noodles next. If you go with Albar or BM and switch to the other, you can use all your brake levers andshifters. The Alba is cheaper to start with…

G

Alberto

on 11 Feb 11Hi Grant, while reading a quote by Blackham recently posted on rivbike.com I had to think of other frame designs i.e. space frames or Pedersen frames which, I would think, are suitable for one thing; comfortable rides with high capacity and low weights. Is it just a coincidence that today’s bicycles are diamond frames and not crossed frames? Thanks,

Grant

on 12 Feb 11There are lots of ways to join the parts on a bike, and most of them have been tried in the last 150 years or so. Pedersens are super comfortable for cruising around on, and it’s no surprise that they were developed in Denmark (I think), where it’s flat. I can’t recreate the development of course, but I’d like to have seen how it went. I’ve ridden one--borrowed it for about a week or so and rode it everyday—and I like it, but you can’t stand and honk up a hill on it, because the rising top tube/saddle area runs into your business. It’s not fair to say “it’s no hill climber,” because it was never intended to be that. It feels great on flat roads and downhills, although no better (to me) than a regular bike with similar high bars.

Space Frames (and other Moulton styles) are another way, but they still use triangulation as their structural base. They just use lots of tiny ones made with tiny tubes, instead of bigger ones of bigger tubes. I’m out of my field and league saying too much about them. Alex Moulton can make me look like Java Man in any sort of technical discussion involving the physics of bike frames. I’ve ridden a Moulton…nice bike…but the small wheels are a bit twitchy for my taste. I’m sure I could get use to them, and I know people swear by them, but I’m more comfortable with the kinds of bikes I know about and am good at.

G

A diamond frame is probably the simplest style that can join the seat postsaddle stemhandlebar, and bottombracketcrank, and

Moon

on 12 Feb 11Hi Grant, If you are still fielding questions, can you spill anything else about the new Riv bike you mentioned above? Is there a time line? A price target? Sizes? Also, a wise bike designer once advised us to ask 3 questions about a potential new bike… —what’s the biggest tire this bike will take? —what about with a fender? —can I get the handlebar higher than the saddle? (although I kind of assume the answer to the last one is yes). Thank you!

grant

on 12 Feb 11Hi Moon, Summer this year; $720 frame fork headset; 48, 55, 60 (for 26, 26, and 700c respectively); 55mm (target), and 52mm at least--the difficulty and compromises ramp up dramatically when you need clearance for 60s, which was the original plan—although the front will take a 60, co you can chopperize it!; and yes/of course/easily/it would be hard not to! It is not firm, but those are the targets. Now you’re the only one outside of RIV who knows… G

Moon

on 13 Feb 11Thank you for your time an for sharing. The bike sounds cool, and very intriguing. Would I just be getting greedy if I ask if the top tube will slope like a Sam Hill? Or if there will be any kind of paint option?... or even a primer-less option to make powder-coating easy?

grant

on 14 Feb 11It will slope up 6-deg. For 3 sizes to fit lots of people, it has to. There will always be a paint option, of course. I think one in three will want it painted (pure guess). Powder-coating…isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.If you want it to not rust, keep the primer and get it wet-painted…or rattlecan it with Krylon, and touch it up whenever it seems to need it… G

This discussion is closed.