While talking to Grant Petersen from Rivendell, he mentioned his love of decades old Chouinard climbing catalogs.

I grew up reading catalogs. The Herter’s catalogue* was the most opinionated one out there, but it was also the most entertaining. Sometimes I’ll read an online comment that, “Rivendell (or Grant) is so opinionated” and it’s supposed to be a criticism. It’s not a criticism. If you want to criticize me, there are way better ways to do it. Tell me I don’t have my facts right, or I don’t give credit where it is due, or my grammar is bad, or my jokes are stupid. That will do the job of hurting my feelings, but being accused of being opinionated is a compliment.

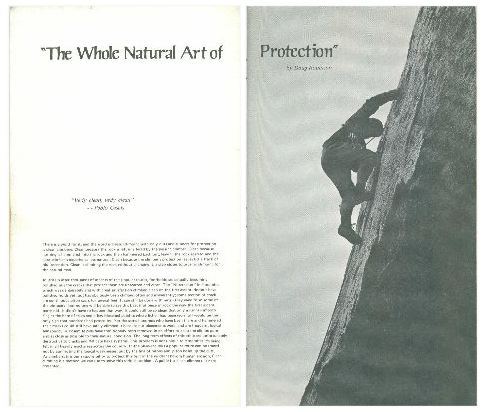

The best catalogues ever were the 1972 and 1973 Chouinard Equipment/Great Pacific Iron Works climbing catalogs. There will never be catalogues like those again. Everybody who writes copy or catalogs or online stuff or reads at all should read those.

Strong praise. Turns out the 1972 Chouinard Catalog is online. Copies of the original catalog fetch $200+ on eBay. But to understand its impact, you first need to know the context around it.

The Chouinard backstory

The backstory to the company is a “scratch your own itch” tale. It starts with pitons, the metal spikes climbers drive into cracks. They used to be made of soft iron. Climbers placed them once and left them in the rock.

But in 1957, a young climber named Yvon Chouinard decided to make his own reusable hardware. He went to a junkyard and bought a used coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil, some tongs and hammers, and started teaching himself how to blacksmith. He made his first chrome-molybdenum steel pitons and word spread. Soon, he was in business and selling them for $1.50 each to other climbers. By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the U.S.

But there was a problem. The company’s gear was damaging the rock. The same routes were being used over and over and the same fragile cracks had to endure repeated hammering of pitons. The disfiguring was severe. So Chouinard and his business partner Tom Frost decided to phase out of the piton business, despite the fact that it comprised 70% of the company’s business. Chouinard introduced an alternative: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks. They were introduced in that 1972 catalog, the company’s first. The bold move worked. Within a few months, the piton business atrophied and chocks sold faster than they could be made.

Looking at the catalog

So what kind of catalog do you put out when you’re reversing your entire business? Chouinard went with a mix of product descriptions, climbing advice, inspirational quotes, and essays that served as a “clean climbing” manifesto. It opens with a statement on the deterioration of both the physical aspect of the mountains and the moral integrity of climbers.

No longer can we assume the earth’s resources are limitless; that there are ranges of unclimbed peaks extending endlessly beyond the horizon. Mountains are finite, and despite their massive appearance, they are fragile…

We believe the only way to ensure the climbing experience for ourselves and future generations is to preserve (1) the vertical wilderness, and (2) the adventure inherent in the experience. Really, the only insurance to guarantee this adventure and the safest insurance to maintain it is exercise of moral restraint and individual responsibility.

Thus, it is the style of the climb, not attainment of the summit, which is the measure of personal success. Traditionally stated, each of us must consider whether the end is more important than the means. Given the vital importance of style we suggest that the keynote is simplicity. The fewer gadgets between the climber and the climb, the greater is the chance to attain the desired communication with oneself—and nature.

The equipment offered in this catalog attempts to support this ethic.

A guide for clean climbers.

A few pages later, there is a guide for clean climbers.

There is a word for it, and the word is clean. Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing. Clean because the rock is left unaltered by the passing climber. Clean because nothing is hammered into the rock and then hammered back out, leaving the rock scarred and next climber’s experience less natural. Clean is climbing the rock without changing it; a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man.

An inspirational quote from Antoine de Sainte Exupery.

The influence

The catalog’s influence is often cited by others. Climber Steve Grossman once talked about the impact it had on his life:

It made a strong push for clean climbing in terms of free protection and people relying less on hammered protection. It had a lot of affect on everybody pretty much in climbing at the time in a way that’s really unparalleled. It laid out the ethics of British rock climbing…Thinking about it now, had that not happened, and had people continued to pound pins and bust flakes off and scar and damage rock, things would be much uglier out there. It’s really pretty horrifying what would have gone on if that revolution hadn’t happened.

David Breashears, climber, mountaineer, and IMAX photographer, also wrote about the influence of the catalog in his autobiography “High Exposure”:

Another serious influence on my developing style came via the Chouinard climbing equipment catalogue of 1972, a slender publication with a Chinese landscape painting on the cover. Its author, the revered rock and ice climber Yvon Chouinard, called for “clean” climbing, proposing that climbers disavow pitons and bolts that scarred or otherwise altered rock. Instead, he advocated the use of metal nuts of various shapes and sizes which slotted into cracks without damage to the rock and could be recovered by the second climber on a rope. He reminded readers of the edict of John Muir, the late-nineteenth-century poet-environmentalist: “Leave no mark except your shadow.”

This ethic of purism and self-control made a profound impact on the climbing community – and on me as well.

A product page that includes a lesson on correct driving.

The Chouinard evolution

Chouinard eventually branched out into clothing too. On a winter climbing trip to Scotland, Yvon Chouinard bought a team rugby shirt to wear rock climbing since it had a collar that would keep the hardware slings from cutting into his neck. Back in America, Chouinard wore it around his climbing friends, many of whom wanted one. Soon, the shirts became a minor fashion craze in the United States. The company decided to spin off the clothing line under a separate name: Patagonia.

Patagonia’s company history details how Chouinard continued to innovate after that. It’s a fascinating story of being inspired by fishermen and football jerseys, taking chances with bold new color schemes and organic fabrics, and a workplace culture that was one of the first to offer child care and a vegetarian-friendly cafeteria.

* “The Oddball Know-It-All” is a look at George Herter, the man behind the Herter’s sporting goods catalog also mentioned by Grant Petersen. Herter wrote all the copy for the catalogs and they’re ridiculous in a good way. He also sold his own books via the catalog. Here’s the opening line to his “Bull Cook and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices.”

I will start with meats, fish, eggs, soups and sauces, sandwiches, vegetables, the art of French frying, desserts, how to dress game, how to properly sharpen a knife, how to make wines and beer, how to make French soap and also what to do in case of hydrogen or cobalt bomb attack, keeping as much in alphabetical order as possible.

Luis

on 15 Feb 11There is an obvious question: why has this kind of writing in catalogs gone away? Or am I just not looking at the right catalogs?

ML

on 15 Feb 11One factor: Feels like most corporate communication (catalogs, web copy, etc.) comes out of a committee. It’s watered down and generic because there are lots of chefs at the keyboard. Plus, they need to play it safe so they don’t offend anyone. On the other hand, Petersen/Chouinard/Herter were-are strong individuals with strong opinions who took control of their copy and made sure it reflected a larger vision. Joel Salatin at Polyface Farms is another good example.

Chad Weinman

on 15 Feb 11@Luis

I am an avid climber and wanted to share that Patagonia (Chouinard climbing eventually morphed into this company) and their catalogs today still capture similar elements.

The catalogs, website and company don’t just market their newest gear; but discuss history, ethics, the environment, and action.

Cheers – Chad

Glenn Street

on 15 Feb 11Yvon Chouinard also wrote a book called “Let my people go surfing. The education of a reluctant businessman.”

If you like the catalogs, you’ll love the book. As expected, the reviews by people is mixed. But you’ll not be left wanting for his opinions if you read it.

http://amzn.com/0143037838

Aaron

on 16 Feb 11J. Peterman’s copy editor killed good catalog writing. Two words for you: Urban Sombrero.

santiago

on 16 Feb 11Nice and inspiring post

Makes me strongly think of Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat, Fugazi, Dischord Records)

(for what it’s worth, the correct spelling is Antoine de Saint-Exupéry)

Ferny

on 16 Feb 11Movie tip of the day….

There is a recent documentary that features Yvon Chouinard – 180 South. Great story with absolutely incredible cinematography and soundtrack. Check out the trailer here – http://www.180south.com/trailer.html

Last time I checked it was available on Netflix streaming. One of my favorite quotes from 180 South, “The hardest thing in the world is to simplify your life; it’s so easy to make it complex.”

SFPaul

on 16 Feb 11I still have that catalog. It was the first time I had heard of clean climbing and it’s essay on it changed my whole thinking. Besides it’s beautifully designed, written and printed.

denise lee yohn

on 18 Feb 11a few years ago i wrote a post “what your underwear says about you,” highlighting all the remarkable things about patagonia, the company yvonne chouinard founded. (http://deniseleeyohn.com/bites/2009/07/06/what-your-underwear-says-about-you/) it was inspired by a page from a patagonia catalog which does in an image what these old chouinard catalogs did in copy - makes a statement. - denise lee yohn

Richard

on 19 Feb 11I have that great catalog somewhere in a box of old climbing books, topos, and some old climbing gear. Along with my first edition of How to Fix your VW for the Complete Idiot and the first Whole Earth Catalog it’s an important work and I’m glad you posted about it.

I agree, it was a turning point for not only Chouinard (and Frost) but also for those of us who followed both him and Royal Robbins in the Valley. It was fun to sit on the sidelines and watch Robbins, Chouinard, Frost, Pratt and others argue with Warren Harding and his group who didn’t want to be told what to do and bolted their way up many routes on El Cap and other faces there.

In the end they were all great pioneers: Harding climbed the Nose route on El Cap with stove legs before Chouinard invented chrome molly bongs and then chocks and other clean climbing tools.

I was in the generation that followed them and when I climbed the Lost Arrow Spire we brought a Chouinard Yosemite Hammer (still have it) and a collection of pitons for hand placing as well as nuts. We did it clean and even took home a Salathe iron piton as a souvenir (still have it).

By the time I did the Nose on El Cap it could be done clean but we still brought the hammer and a few pitons (Chouinard bongs) just in case. Never used them.

In the very early days of it I visited Chouinard in Ventura at the Great Pacific Iron works and I must say, everything you say in your post has been true of his business sense since the very beginning and remains true in his Patagonia clothing line. He understands how to grow a business, yet keep it small enough to be sustainable. He has a great sense of the balance between form and function and like Apple products, once you get in his groove it’s tough to buy inferior products from other vendors (who are usually imitating him).

Scott

on 21 Feb 11Although lacking in much of the philosophy of climbing, the Petzl catalogues are still a treasury of some of the art, much of it available online at this point.

hdfbew

on 22 Feb 11the-north-face-triclimate-jackets

Mike Papageorge

on 22 Feb 11Cool to see this on here. I had some late-80’s patagonia catalogues that were really good too.

Love Yvon’s idea of “Cradle-to-Cradle” product responsibility for clothing and that Patagonia practices it when they can… “Let my people go surfing” is worth a read to learn about their early pioneering efforts in business and in the wild.

This discussion is closed.