Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), the father of American landscape architecture, may have more to do with the way America looks than anyone else. Beginning in 1857 with the design of Central Park in New York City, he created designs for thousands of landscapes, including many of the world’s most important parks.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), the father of American landscape architecture, may have more to do with the way America looks than anyone else. Beginning in 1857 with the design of Central Park in New York City, he created designs for thousands of landscapes, including many of the world’s most important parks.

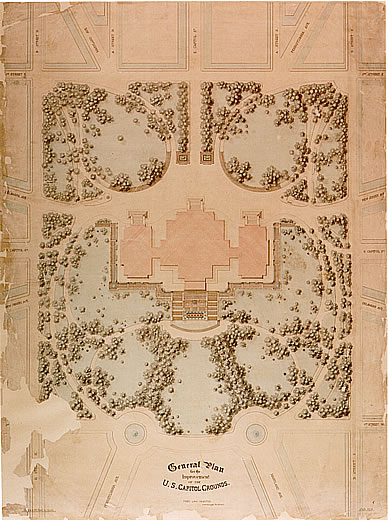

His works include Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, Mount Royal in Montreal, the grounds of the U.S. Capitol and the White House, and Washington Park, Jackson Park and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. (The last of those documented excellently in Erik Larson’s book The Devil in the White City.) Plus, many of the green spaces that define towns and cities across the country are influenced by Olmsted.

Below, ten lessons from Olmsted’s approach:

1) Respect “the genius of a place.”

Olmsted wanted his designs to stay true to the character of their natural surroundings. He referred to “the genius of a place,” a belief that every site has ecologically and spiritually unique qualities. The goal was to “access this genius” and let it infuse all design decisions.

This meant taking advantage of unique characteristics of a site while also acknowledging disadvantages. For example, he was willing to abandon the rainfall-requiring scenery he loved most for landscapes more appropriate to climates he worked in. That meant a separate landscape style for the South while in the dryer, western parts of the country he used a water-conserving style (seen most visibly on the campus of Stanford University, design shown at right).

This meant taking advantage of unique characteristics of a site while also acknowledging disadvantages. For example, he was willing to abandon the rainfall-requiring scenery he loved most for landscapes more appropriate to climates he worked in. That meant a separate landscape style for the South while in the dryer, western parts of the country he used a water-conserving style (seen most visibly on the campus of Stanford University, design shown at right).

2) Subordinate details to the whole.

Olmsted felt that what separated his work from a gardener was “the elegance of design,” (i.e. one should subordinate all elements to the overall design and the effect it is intended to achieve). There was no room for details that were to be viewed as individual elements. He warned against thinking “of trees, of turf, water, rocks, bridges, as things of beauty in themselves.” In his work, they were threads in a larger fabric. That’s why he avoided decorative plantings and structures in favor of a landscapes that appeared organic and true.

3) The art is to conceal art.

Olmsted believed the goal wasn’t to make viewers see his work. It was to make them unaware of it. To him, the art was to conceal art. And the way to do this was to remove distractions and demands on the conscious mind. Viewers weren’t supposed to examine or analyze parts of the scene. They were supposed to be unaware of everything that was working.

He tried to recreate the beauty he saw in the Isle of Wight during his first trip to England in 1850: “Gradually and silently the charm comes over us; we know not exactly where or how.” Olmsted’s works appear so natural that one critic wrote, “One thinks of them as something not put there by artifice but merely preserved by happenstance.”

4) Aim for the unconscious.

Related to the previous point, Olmsted was a fan of Horace Bushnell’s writings about “unconscious influence” in people. (Bushnell believed real character wasn’t communicated verbally but instead at a level below that of consciousness.) Olmsted applied this idea to his scenery. He wanted his parks to create an unconscious process that produced relaxation. So he constantly removed distractions and demands on the conscious mind.

For example, his designs subtly direct movement through the landscape. Pedestrians are led without realizing they’re being led. If you’ve ever gotten lost on one of Prospect Park’s paths, you’ll understand the point. It’s a strange sensation of feeling lost yet completely confident that you can easily return to your starting point.

5) Avoid fashion for fashion’s sake.

Olmsted rejected displays “of novelty, of fashion, of scientific or virtuoso inclinations and of decoration.” He felt popular trends of the day, like specimen planting and flower-bedding of exotics, often intruded more than they helped.

For example, he contrasted the effect of a common wild flower on a grassy bank with that of a gaudy hybrid of the same genus, imported from Japan and blooming under glass in an enameled vase. The hybrid would draw immediate attention. He observed, but “the former, while we have passed it by without stopping, and while it has not interrupted our conversation or called for remark, may possibly, with other objects of the same class, have touched us more, may have come home to us more, may have had a more soothing and refreshing sanitary influence.”

6) Formal training isn’t required.

Olmsted had no formal design training and didn’t commit to landscape architecture until he was 44. Before that, he was a New York Times correspondent to the Confederate states, the manager of a California gold mine, and General Secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. He also ran a farm on Staten Island from 1848 to 1855 and spent time working in a New York dry-goods store.

His views on landscapes developed from travelling and reading. When he was young, he took a year-long voyage in China. And in 1850, he took a six-month walking tour of Europe and the British Isles, during which he saw numerous parks, private estates, and scenic countryside. He was also deeply influenced by Swiss physician Johann Georg von Zimmermann’s writings about nature’s ability to heal “derangements of the mind” through imagination. Olmsted read Zimmermann’s book as a boy and treasured it.

7) Words matter.

Olmsted wrote often and thought hard about the words he used. For example, he rejected the term “landscape gardening” for his own work since he felt he worked on a larger scale than gardeners. He wrote, “Gardening does not conveniently include exposing great ledges, damming streams, making lakes, tunnels, bridges, terraces and canals.” Therefore, he said, “Nothing can be written on the subject in which extreme care is not taken to discriminate between what is meant in common use of the words garden, gardening, gardener, and the art which I try to pursue.” He also wrote extensively on design principles and his words still inspire many in the field to this day.

8) Stand for something.

By the time he began work as a landscape architect, Olmsted had developed a set of social values that gave purpose to his design work.

From his New England heritage he drew a belief in community and the importance of public institutions of culture and education. His southern travels and friendship with exiled participants in the failed German revolutions of 1848 convinced him of the need for the United States to demonstrate the superiority of republican government and free labor. A series of influences, beginning with his father and supplemented by reading such British writers on landscape art as Uvedale Price, Humphry Repton, William Gilpin, William Shenstone, and John Ruskin convinced him of the importance of aesthetic sensibility as a means of moving American society away from frontier barbarism and toward what he considered a civilized condition.

His writings show that, in his view, he wasn’t just making pretty, green spaces. He was democratizing nature...

It is one great purpose of the Park to supply to the hundreds of thousands of tired workers, who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of God’s handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month of two in the White Mountains or the Adirondacks is, at great cost, to those in easier circumstances.

...and healing people’s mental conditions.

It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character, particularly if this contemplation occurs in connection with relief from ordinary cares, change of air and change of habits, is favorable to the health and vigor of men…The want of such occasional recreation where men and women are habitually pressed by their business or household cares often results in a class of disorders the characteristic quality of which is mental disability, sometimes taking the severe forms of softening of the brain, paralysis, palsey, monomania, or insanity, but more frequently of mental and nervous excitability, moroseness, melancholy, or irascibility, incapacitating the subject for the proper exercise of the intellectual and moral forces.

9) Utility trumps ornament.

There was always a “purpose of direct utility or service” to Olmsted’s work. Service preceded art in his work. He felt trees, flowers, and fences without purpose were “inartistic if not barbarous.” He wrote, “So long as considerations of utility are neglected or overridden by considerations of ornament, there will be not true art.”

This could be seen in the way he treated practical aspects of his work. Providing for adequate drainage and other engineering considerations mattered as much as arranging surface features.

This could be seen in the way he treated practical aspects of his work. Providing for adequate drainage and other engineering considerations mattered as much as arranging surface features.

He was also into sustainable design and environmental conservation long before it was in vogue. He wrote, “Plant materials should thrive, be non invasive, and require little maintenance. The design should conserve the natural features of the site to the greatest extent possible and provide for the continued ecological health of the area.”

10) Never too much, hardly enough.

Olmsted fought against distracting elements. He constantly simplified the scene, clearing and planting to clarify the “leading motive” of the natural site. Though he often faced criticism from those who found his style too rough and unkempt, Olmsted was as proud of what he didn’t do as what he did do. Thirty years after he helped to design Central Park, he observed to his ex-partner, Calvert Vaux, “The great merit of all the works you and I have done is that in them the larger opportunities of the topography have not been wasted in aiming at ordinary suburban gardening, cottage gardening effects. We have let it alone more than most gardeners can. But never too much, hardly enough.”

Sources: The Olmsted legacy, Seven ‘S’ of Olmsted’s Design, The Design Principles of Frederick Law Olmsted, Olmsted and America’s Urban Parks, Central Park and the battle for organic lines in urban settings, and The genius behind Boston’s Emerald Necklace (PDF).

Carl

on 23 May 11It’s always a great technique to see how design philosophies of one discipline may relate to another. Thanks for the post. (Should have done a spell check on “Suburdinate” though.)

Christopher S. Castleman

on 23 May 113) The art is to conceal art.

Christopher S. Castleman

on 23 May 11This idea holds true in software development, where the user should not be distracted by flashy features, but rather be unaware of them and naturally enjoy the application as a whole.

Anthony Vitagliano

on 23 May 11I grew up in NYC and walked through central park. The similarities between the two designs were remarkable… It felt just like home.

Radex

on 23 May 11I’m absolutely amazed how design principles that made sense in landscape architecture can be applied to software development. I had the same feeling after I’ve read Rework, allegedly business book, but in reality I would say a philosophy book.

“The art is to conceal art.”—tough advice, but after seeing 37s software I understand why it’s so important.

Donny

on 23 May 11Thank you for this beautiful piece. Having been pleasantly taken aback many times by the effect of ‘getting lost’ in Central Park, I am deeply appreciative of the thought behind achieving precisely this !

Chris

on 23 May 11I really wish people would realise that “no formal training is required”. People these days are far too fearful to try ne things because they believe they are not experienced enough to do it – people have forgotten how to learn new things. It is not from reading but from doing that we become great at things so why don’t we all give things more of a try.

Great post as always – lessons to be learnt everywhere!

Jason Clark

on 24 May 11http://www.olmstedparks.org/about/frederick-law-olmsted/

We’re lucky enough in Louisville to see his parks and parkways all through the city. It’s a true gem. Great post!

Naomi Tapia

on 24 May 11My favorite on the list is to “stand for something”... don’t they say that if you don’t stand for something that you’ll stand for anything (or is it nothing?). You’ve really did a lot of research for this post – much appreciated!

Maddy

on 24 May 11@Naomi – it’s “If you don’t stand for something you’ll fall for anything.”

dylan

on 24 May 11the capitol grounds are totally an owl. creepy!

Remi Gerard

on 24 May 113) Aim for the unconscious. should be #4 ;) Great piece anyway. Will read it again and again until it enters my bones

sawebdesigns

on 24 May 11great read Ill take this in heart

Sharingmatters

on 24 May 11Words matter – I repeat that when it comes to job titles. People associate themselves with few words describing their work and they really influence their perspective and focus while doing their job. Many times we just forget about this.

chapstickaddict

on 24 May 11Syracuse, NY has its own mini Central Park in Olmsted-designed Onondaga Park in the historic Strathmore neighborhood. I lived in Strathmore prior to moving to NYC, and Central Park has always made me, too, feel like I was home. And then Prospect Park, too, once I moved to Brooklyn. I have great admiration for Olmsted. What a wonderful legacy he’s left to share with us.

ducttape101

on 24 May 11This is a great summary. These rules seem to constitute the opposite of every rule governing Frank Gehry’s work. They articulate perfectly the negative reaction I have to everything that man has done.

we ♥ letterpress

on 25 May 11This is a great summary! We like the idea that you don’t have to study arts to be an artist. Therefore, we publish great (letterpress) art on we ♥ letterpress, independent from the background of the artist. Thanks for posting this!

Rich Collins

on 25 May 11Utility trumps ornament

Rich Collins

on 25 May 11Utility trumps ornament

This seems entirely lost on most web designers

rick

on 25 May 11I walked our puppy through our FLO park everyday (Lake Park in Milwaukee).

There are so many details that make me wonder if he designed them specifically or just uncovered the land and left it as he found it.

Karin Wood

on 25 May 11I adore Central Park and its picturesque nooks and crannies, and I think it is genius.

But it should be pointed out that Olmsted owes a debt to the “undesigned design” of the English landscape tradition and designers like Humphry Repton and Capability Brown, who were active 75-100 years earlier. Others too: http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/olmsted-his-essential-theory

Here’s an interesting example: going up the slopes of Belvedere Castle, Olmsted planted trees with increasingly small leaves, all to make the “castle” (which is tiny!) appear larger, and the hill farther away, when viewed from the Mall. Brown and Repton used the same trick.

Not to take anything away from FLO’s achievements, or our enjoyment of his work 150+ years later…

Jon A Peterson

on 26 May 11The author shows considerable familiarity with Frederick Law Olmsted, who I have long admired and have myself written about, and it is easy to become intoxicated by his intellect and remarkable achievements. But it is simply nonsense to claim that he “may have more to do with the way America looks than anyone else.” The grid street system, the superhighway, the balloon framing system, the post-World War II suburban track: an almost interminable list of visually dominate forms could be compiled without once touching on Olmsted’s influence. The tragedy is that he wasn’t more influential. Before the late 1960s, barely anyone remembered him and those who did, mostly historians, recalled him as a writer on the antebellum south.

Dey Alexander

on 27 May 11I think I’m love :) I don’t think I’ve read anything I agreed with more wholeheartedly. At least not in a while.

This discussion is closed.