Below: Q&A with Chris Wanstrath, CEO and Co-Founder of GitHub. This is part of our “Bootstrapped, Profitable, & Proud” series which profiles companies that have $1MM+ in revenues, didn’t take VC, and are profitable. Chris and Tom from GitHub have also answered reader questions in the comments section of this post.

What does your company do?

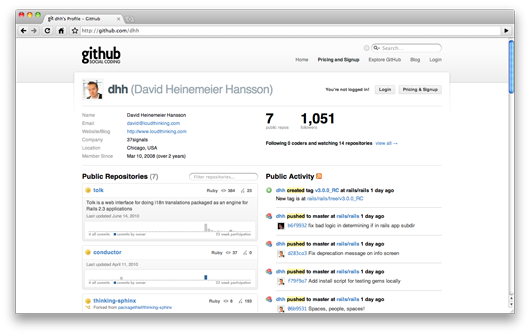

We offer public and private source code hosting to companies and open source projects using either git or Subversion. What we want to do is lower the barrier of contributing to projects, both public and private. Submitting a patch to an open source project should be about the code, not the process of submitting the patch. Working with your coworkers, either in the same office or across the world, should be about moving your project forward and not about managing clumsy tools.

We also offer git training, provide git learning materials, and sponsor open source projects.

How do you explain to “normal” folks (e.g. your mom, someone you meet at a cocktail party, etc.) what your company does?

GitHub is like Wikipedia for programmers. You can edit files, see who changed what, view old versions of files, and access it from anywhere in the world – except you’re working with source code instead of encyclopedia data. Companies use it to build software and websites, while hobbyist programmers use it to find and share projects.

The business model is simple: if you want to share your source code with everyone and make it public, you don’t pay anything. If you need to hide your source code because it’s private and runs your business, you pay.

L to R: Rick Olson, Tom Preston-Werner, and Chris Wanstrath. (Photo by Dave Fayram.)

How big a part of the business is training?

Training isn’t a huge part of our revenue, but if we can make some money teaching people how to better use git then everyone wins. It’s also great to meet customers in person and develop a real relationship with them. Also, we like to send Scott Chacon (our resident git wizard) all over the world.

Sponsoring open source and git learning materials is good for the whole world, but we do that stuff because we love it. If a GitHubber wants to spend some of their time working on an open source project, that makes us very happy.

How did the business get started?

At first GitHub was a weekend project. Tom Preston-Werner and I were hanging out at a sports bar after a local programming meetup when he told me his idea for a git hosting site. It’d be a place to easily share code and learn about git, a git hub. It started more out of necessity than anything else: we both loved git but there was no acceptable way to share code with others. Tom thought I’d be interested in helping fix the problem, and I was.

We began meeting on Saturdays to build the site piece by piece. We’d grab brunch, talk about ideas we had for the site, then get to work. Tom would design pages or features and I’d implement them. As soon as the basics were in place we started using GitHub at my day job, a startup I had cofounded with PJ Hyett. It was a great way to improve the site, as PJ and I were using GitHub daily and really getting a feel for what was missing and what was working.

One thing Tom had learned at his previous venture, Gravatar, was that offering a resource intensive service for free was a losing proposition. In that case it was high traffic image hosting, but in GitHub’s case it was git hosting. Storing and transferring code was going to stick us with a large server bill. We needed a way to recoup costs.

With that in the back of our minds, we launched a free public beta for our friends. The site immediately started taking off. You could create public or private repositories for free and people were starting to use the site for their business’s code – not that surprising considering PJ and I were doing the same thing. Soon, however, we had people emailing us asking how they could pay for private repositories.

At this point we realized GitHub could probably do more than just recoup costs. It could be a real business. We decided to continue to offer unlimited public repositories for free, but we’d charge for private repositories. In other words, we’d charge the people asking to be charged.

PJ became a cofounder of GitHub and we stopped working on our startup. GitHub was now our startup. The three of us launched the site officially on April 10th, 2008 and have been running the business ever since.

How much cash did you need to get up and running? How did you get that money?

It all started with a domain, a cheap slice from Slicehost, and some stock art. When we decided to start a real business we had the usual expenses for setting up a legal entity – a few hundred bucks that we scrounged together.

The real cost was supporting ourselves as we grew the site and the business. PJ and I did consulting to pay the bills while Tom worked a full time job. As the business grew, we came up with a system that would let us gradually work up to full time salaries.

We’d start by getting small paychecks, then each month, assuming we hit certain monetary goals that month, we’d increase the size of the paychecks. Eventually, if all went well, we’d be making full time salaries.

It worked out pretty well. A few months we failed to meet the goals we set and, as a result, our paychecks didn’t get any bigger. But we hung in there and ended up with the salaries we had planned on.

How successful is your business?

That we’re able to convince great people to work with us and pay them really well, all without any sort of outside funding, is the most exciting thing for me. By that metric, we’re very successful.

As far as numbers go, we have hundreds of thousands of users, tens of thousands of paying customers, and almost a million repositories – with thousands more added each day. All in just over two years.

What is your work environment like?

Chaotic, but that’s the way we like it. We don’t have managers, instead we decide as a company what features or ideas are priorities. Whoever is the most interested in a feature ends up implementing and owning it.

It might sound crazy, but it works out really well. It’s a great way to make sure people are interested in what they’re working on, and that as a company we’re working on things that matter. If it’s lame, no one’s gonna do it. We all use the site so everyone has a pretty good idea of what’s missing or not working. We’re also friends with many of our customers, which helps when deciding what is and isn’t a priority.

Culturally we operate like a distributed company. We have an office in downtown San Francisco, but it’s rare that everyone is in the same place at the same time. The real office, the place everyone shows up every day, is our Campfire room. At first this was out of necessity – we couldn’t afford to rent any office space so we’d work out of homes or coffee shops and keep in touch online. But now we believe it’s a better way to operate. GitHubbers have the freedom of heading into the office and working together in person one day, then hopping on a plane and continuing to work together while across the world the next day. There are no office hours, people just focus on getting things done instead of clocking in and out.

And we’re all about getting things done. We’re very lucky to be working (mostly) on a web app, which means it’s super easy to make changes fast. We’ve learned it’s much better to ship it now and fix it later, once you can see how people are using it, than it is to let it linger in development forever. Just ship it.

Why is it so much better to ship it now and fix it later? Any examples come to mind?

You can’t always be right and nothing’s ever going to be perfect – embracing this is a huge competitive advantage. Shipping early and often lets you see how people are actually using your site and allows you to react accordingly. Does that feature you shelved even matter? Is a feature you didn’t think of sorely needed? Has anyone even hit that bug you were worried about? It’s very easy to get too close to something and get a bit myopic.

It’s not easy to prioritize and you don’t have infinite time, so let your customers help. See what they want, and do that by shipping something as soon as it’s useful.

Making shipping a priority is more fun, too. Deadlines feel like work, shipping feels like a challenge.

The most recent launch I was a part of was our new Organizations feature. As soon as we had something useful we invited a few friends into a private beta. Watching how they used the new system helped us perfect a few workflows, add some much needed functionality, and iron out nasty bugs.

What’s your goal with the company?

In five years I want to love my job and love the people I work with. We do want to keep growing, and make more money, and hire more people, and make something our customers love, but the most important thing is we keep having fun. I hope GitHub is forever an awesome place to work and an awesome website to use.

As long as we have really great people who are passionate about what they do and enjoy their jobs, we’re going to continue to provide a really great service for our customers (and ourselves).

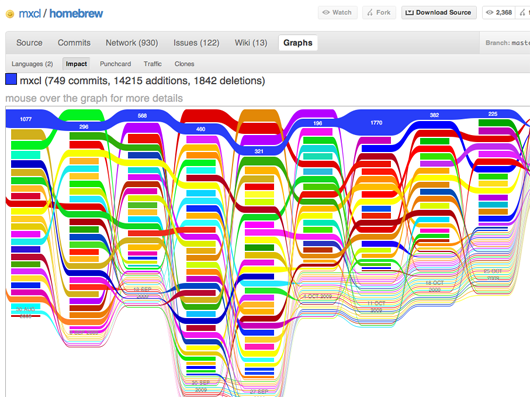

GitHub gives you different ways to visualize what’s happening with

your code. Here each color represents someone who has contributed to

the homebrew project – the size of their color represents how much of

an impact they’ve had on the code.

Any examples of a time you ignored the advice/opinions of others and went your own way?

Tom has a pretty great article about turning down $300,000 to work at GitHub.

I was going to be faced with a choice sooner than I had anticipated. I could either sign on as a Microsoft employee or quit and go GitHub full time…In the end, just as Indiana Jones could never turn down the opportunity to search for the Holy Grail, I could no less turn down the chance to work for myself on something I truly love, no matter how safe the alternative might be. When I’m old and dying, I plan to look back on my life and say “wow, that was an adventure,” not “wow, I sure felt safe.”

We generally ignore the advice/opinions of others as a rule. GitHub is the company of the compelling argument – every decision needs to stand on its own merit. That someone successful (or unsuccessful) tried something before might matter in a discussion, but what matters more is how the idea itself applies to the situation.

Plenty of people have told us to abandon our git training (“It doesn’t scale!”) or to not offer an on-premise version of the site (“SourceForge couldn’t pull it off!”), but both products are working for us and our customers. Every company is different and we like to keep an open mind, listen to our customers, and listen to ourselves.

What’s been the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome as a company?

The first year or so of the company reminded me a lot of the awkward teenage phase of self-discovery. GitHub the company had sort of sprung up from this side project, so we never had any big vision or dream or aspirations. We just wanted to work on something cool. I’d love to say that’s all you need, but we’ve learned there’s more: you need to have a vision and a philosophy. Everyone (all the founders, at least) need to be on the same page. The hard part is finding that page.

Do we make web apps, or just do source control? What do we pay our employees? Should we speak at conferences? How do we approach customer support? All of these might seem like isolated questions, but they’re all directly related to the philosophy of the company. Once you know what the company stands for they’re all much easier to answer. We were having a hard time answering each question individually before we really figured out what GitHub the company was all about.

Do you have this philosophy written out somewhere? Or does everyone who works there just know what it is organically?

We talk about it during the hiring process, which we take very seriously. We want any potential GitHubber to know what they’re getting into and ensure it’s a good fit. Part of that is having dinner and talking about stuff like the culture, philosophy, mistakes we’ve made, plans, whatever.

Early on we made a few hires for their skills with little regard to how they’d fit into the culture of the company or if they understood the philosophy. Naturally, those hires didn’t work out. So while we care about the skills of a potential employees, whether or not they “get” us is a major part too.

The office. (Photo by Dave Fayram.)

What else is interesting about your story?

Two of the three GitHub founders are college dropouts.

Do you think there’s a reason why or is that just a coincidence?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence – Tom and I both dropped out of school to get programming jobs. His was with a startup, mine with a more conventional business, but we both left because we couldn’t wait to get out into the real world. It was inevitable we’d end up starting our own thing.

PJ finished with a computer science degree, but he was basically on a plane to San Francisco the moment he got his diploma. He had a job (where he and I met) at CNET months before graduating and was coming up with side projects and businesses during his entire college career.

I personally have no opinion on whether you should or shouldn’t get a college degree as I’ve met fascinating and successful people on both sides of the fence, but the reasons I didn’t do well in school are the same reasons I didn’t do well in a corporate structure and started my own company. I think a lot of people would be much happier working for themselves but never realize it. Your job doesn’t have to suck.

What advice do you have for someone considering starting a business?

Do it, but be smart about it. Use your brain. Think about what make the most sense for you. Worry about every dollar you spend before (and even after) you’re profitable. Focus on the things that matter and don’t waste time endlessly redesigning your site or tinkering with new technologies. There’ll be plenty of time for that later.

Below, a video walkthrough of GitHub’s office:

Visit GitHub

More “Bootstrapped, Profitable, & Proud” posts [Signal vs. Noise]

Travis Bell

on 03 Aug 10Awesome to see GitHub featured here. I’ve used GitHub for years now and love it. Everything I do is through it and it’s constantly impressing me. Kudos to a great app!

George Coltart

on 03 Aug 10Great startup story. Did you bootstrap in the sense of putting some of your own money in to get by, or has every cost been funded through revenue?

George c

on 03 Aug 10Sorry just re-read the “few hundred bucks” line again…

Jason Klug

on 03 Aug 10Loving the Bootstrapped series… thanks!

The article mentioned GitHub started as a weekend project—what had you been working on during the week? “Straight” jobs, freelancing, school…?

iain

on 03 Aug 10I have a question: How does it feel to be on a blog called “svn”? ;)

Seriously though: github is awesome!

Jason Klug

on 03 Aug 10Also, what is it like programming for programmers? Does the feedback get pretty intense (+/-), or do you prefer not to focus on it?

Jona Fenocchi

on 03 Aug 10How many hours of sleep during the week did you guys get while you were getting GitHub off the ground? 6? 4? How did you balance having a full-time job and personal life while trying to get GitHub started?

Loving the BP&P series, 37signals! Thanks! And thanks, GitHub!

Scott

on 03 Aug 10Neat story. I’m glad you added the “How do you explain to “normal” folks” information. Being non-technical I was not sure from the first paragraphs what git does while the “normal folks” info makes it clear its a system for software projects. I’m liking this series, keep it up.

jeremy

on 03 Aug 10As I understand, Engine Yard gave them free hosting for a long time. Saving a couple hundred thousand dollars in hosting and scaling costs probably should be mentioned. Either way, GitHub rocks.

Tom Preston-Werner

on 03 Aug 10@Jason Klug – I was working at Powerset full time when we started working on GitHub. Programming for programmers is both awesome and frustrating. Building something that we use every day is extremely rewarding. At the same time, programmers are very opinionated and we can’t listen to everybody, so some people feel like we’re not paying attention to what they want. It’s our job to figure out what developers really want and try to make the experience as simple and powerful as possible.

@Jona Fenocchi – I got plenty of sleep during the period we were building GitHub on the side; I don’t operate well unless I get about 8 hours of sleep a night. However, I spent tons of time on evenings and weekends working on the site. My wife was in Costa Rica doing fieldwork for her PhD, which freed up a lot of time for me to concentrate on code and getting GitHub off the ground. One piece of advice: if you’re spending ungodly hours in front of a computer, make sure you get out into nature at least once a week. I mountain bike and hike on a regular basis and it really helps to recharge the creative juices that make working on a startup really enjoyable.

@jeremy – We had a partnership with Engine Yard. They gave us free hosting and we gave them publicity. Good partnerships are key to bootstrapping a startup. When you can get a win/win out of a partnership and save a bunch of money, it’s an obvious thing to do.

Ron

on 03 Aug 10How important to your success was the choice of Erlang? What are the founders’ salaries?

Mike

on 03 Aug 10Great interview! Would you be willing to share your vision and philosophies for GitHub, Chris?

Chris Wanstrath

on 03 Aug 10Jona Fenocchi: I love something I heard Cameron Moll say recently: “I don’t believe in work-life balance. I believe in priorities.”

Instead of “I have to work on GitHub today,” I like to think, “I have to do X today.” It makes it a lot easier for me to manage my time that way.

Jona Fenocchi

on 03 Aug 10@Tom & Chris, thanks for your responses and insights. I believe the distinction most clearly contrasts working for oneself versus working for someone else. And 8 hours is a really nice number. ;-)

Martin Pilkington

on 03 Aug 10You started out with git support and later added subversion support. Have you considered adding support for other systems such as bazaar or mercurial? I’d love to use github, but I personally can’t stand git.

David

on 03 Aug 10Github is awesome. I’ve only been using it recently as I’ve started to do more development work and it’s been indispensible in helping to get me up to speed on so many things!

Thanks a lot fellas and keep up the good work!

Ps. Agree with your comments on hiring the right people… It’s vital to get somebody who can actually see where you are trying to go and can fit into what you already have – otherwise it’s a destined to failure ;-)

fr

on 03 Aug 10Does apple pay github people for pub ?

Alex

on 03 Aug 10I’ve used GitHub since 2008. Great web service, keep up the good work!

Chris Wanstrath

on 03 Aug 10Martin Pilkington: We want to make it easier for people to collaborate with others. If that means adding hg and bazaar support, so be it! We know not everyone loves git and we don’t want that to be a barrier.

David: Thanks!

fr: We’re reading a story about how horrible Apple is on that iPad.

Sanju

on 03 Aug 10did you now have your own server running up for all the repositories . if yes, when did you plan to move from slice host to your own server?

if no, how much does it really cost to keep so much server space. I guess there will more public repositories than private (paying customer) repositories.

Elizabeth

on 03 Aug 10Great interview! Especially liked the piece of advice at the end.

Scott

on 03 Aug 10I’m envious of the beautiful office space.

joe shmoe

on 03 Aug 10There’s bootstrapped and then there is getting hundreds of thousands of free hosting from Engine Yard to help you get boot strapped. I’ve heard that EY gave about $25k worth of hosting and got about $3k worth of github services each month toward the end. And in the beginning ey got almost zero github services in repayment for a lot of hardware.

Tom

on 04 Aug 10inspiring words…I wanna work for github!!

Brent

on 04 Aug 10Great article. Thanks for sharing so much. GitHub rocks and it’s cool to hear how you got it all going. Best of luck!

Gwyn from smartassess

on 04 Aug 10...but what a crayzee name! over in the UK, a git is an idiot…! your name means a collection of idiots! (just getting my own back! – well done guys!)

Brandon Ferguson

on 04 Aug 10@joe shmoe – It was a partnership. You have to remember that EY was a startup looking to get their name out there as well. So it was mutually beneficial. When a site that’s popular with your core audience hosts with you and you get to plaster you name on their site it’s fantastic marketing. Especially you have to considered the trade off wasn’t much between the two in the beginning. Of course github outgrew and had to move on, but partnerships are very much a part of bootstrapping. One more reason to network with your local startup community eh?

Romain

on 04 Aug 10Could not agree more. I think that Github’s partnership with Engine Yard is a great example of how to be creative when you haven’t got cash to burn (and even if you have actually).

Glenn Gillen

on 04 Aug 10Anybody who has met the guys from Github will know first hand how talented they are. Being able to have all your git problems solved by grabbing one of them for 5 minutes after a conference is incredible.

I think being so approachable and generous must go a long way to boosting their bottom line, both from the indebtedness I and others feel for their help and just from a karmic perspective.

Chris Wanstrath

on 04 Aug 10Glenn Gillen: Awesome, thanks for the comment :)

Joe shmoe

on 04 Aug 10@ Brandon fergenson

Agreed that partnerships are beneficial like that. But this one was so lopsided it could hardly be called a partnership. And when the github guys were asked to even it out a little bit they just bailed rather then trying to work out the partnership. Ey put out over $350k in hosting fees over that year and made maybe $10k from github. Then when asked to even out the partnership they just left and badmouthed Ey even after all the help that was given. My beef is just that they should have mentioned in this interview how much free shit and support and even code written for them from Ey, not a true bootstrap if up you know the real math.

Tom Preston-Werner

on 04 Aug 10@Joe schmoe – We had a business partnership with EY that we found mutually beneficial. Eventually we decided that we needed to move to a different host. I outlined the reasons we chose to do so in a long blog post entitled GitHub is Moving to Rackspace.

IanM

on 06 Aug 10What strategies where put into place to get the word out about GitHub? Was there an early day marketing budget and if so how was it spent?

This discussion is closed.