The overwhelming way: Head down forever and hope there will be a big payoff at the end.

The overwhelming way: Head down forever and hope there will be a big payoff at the end.

The problem: The finish line always seems like it’s miles away. You spend 99% of your time anxious and only experience joy at the end (if ever). Sometimes you’re so intimidated by the idea, you give up.

A more soothing approach: Break what you’re doing into smaller, incremental units. Then you get to celebrate each step of the way instead of waiting until the end.

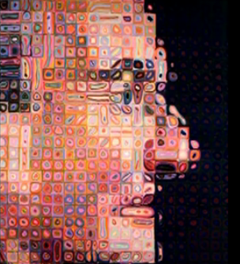

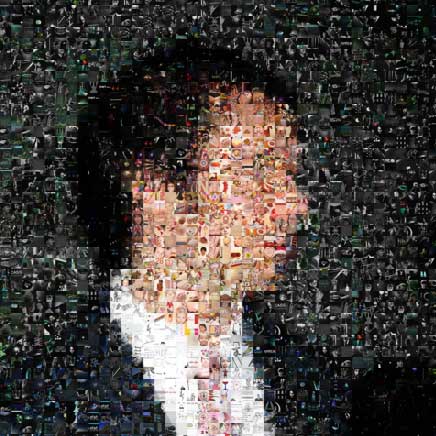

Artist Chuck Close is someone who chooses this approach. He’s famous for his portraits of faces despite suffering from prosopagnosia — aka face blindness. He overcomes this by working in incremental units. He uses a pixilated approach to painting that turns faces into a grid of individual squares. In this interview, he explains why.

The fact that there are incremental units is driven by my learning disability. I was overwhelmed by the whole. How am I going to make a head? How am I going to make a nose? It’s too overwhelming. It makes me too anxious. But if I break it down into a lot of little decisions…

This was a coping mechanism I used all throughout school and everything that I did. Take something overwhelming and anxiety provoking and make it into little, not-so-scary decisions and have it be a positive experience. Because every time I completed a square, I didn’t have to wait until the end to get pleasure. I could solve one little problem at a time and the pleasure came with each one of those.

Solve one little problem at a time and you get a steady IV drip of pleasure. And that’s great motivation to keep going.

Another money quote from Close: “I’ve always thought that problem-solving is highly overrated and that problem creation is far more interesting.” Perhaps that explains why he’s moved away from his 3D weakness and focuses on “problems” that exist in the flat realm, where he excels.

In real life, if you move your head a half-an-inch, to me, it’s a whole new face I have never seen before. But if we flatten it out, I have — and I take photographs — I work from photographs, and I make flat things called paintings and prints. I have virtual photographic memory for anything that is flat. And I want to commit them to memory. And the only way I can really do that is to flatten them out, scan them, make these — make these drawings and paintings and prints. And then they enter the — my memory bank in a different sort of way.

Neat to see how, by working in 2D, he redefines the task and overcomes his weakness.

Andy

on 04 Nov 10Very nice – this is one of the best posts I’ve seen on this blog. Thanks.

Andy

on 04 Nov 10ps – the post would be even better if you eliminated everything after “Another money quote…”. Less is more – I think I learned that by reading your blog. :-)

David Andersen

on 04 Nov 10Nice post Matt.

YA

on 04 Nov 10Funny you should say that Andy. I so loved the first part that I actually stopped reading just before “Another money quote”.

I derived enough pleasure from the first part and didn’t want to taint it with more.

Michael

on 04 Nov 10I disagree. At first, I was content to read the post only before the jump. After I thought about it more, I read the rest of it. I enjoyed it more that way.

That’s how good writers use the teaser—they deliver the payload on the home page, and let people who appreciate it that much soak up the rest.

Benjamin Welch

on 04 Nov 10Really enjoyed this post. Thanks Matt.

David O.

on 04 Nov 10I find this methodology very useful when learning to play a new song or instrument.

VA

on 05 Nov 10Reminds me of the Pomodoro Technique. Regardless, the IV drip method or the Pomodoro – I can vouch that both of them work! When the going gets tough, and they seldom go easy, it’s time to micro-solve.

Brainnovative

on 05 Nov 10What you’re talking about is a little part of the Kaizen philosophy. There’s plenty more of excellent techniques to deal with change and improvement where that one came from. Here’s a great read. It really helped me introduce some major changes in life with small steps.

好秘书

on 05 Nov 10That’s how good writers use the teaser—they deliver the payload on the home page, and let people who appreciate it that much soak up the rest.

Wholesale Flea Market Products

on 05 Nov 10Quite an informative one, got to know about a different perception to look at the things. This is indeed something that would indeed be a good one to give a try at. It is more about the way it would result into than the method adopted in this case.

merle

on 05 Nov 10When you’re working on a project, don’t fixate on when you’ll finish or the money you’ll make.

Those things will take care of themselves. They might not even happen on your current project.

Focus on learning, doing good work and making steady progress.

Matt Redard

on 05 Nov 10How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. Good post.

codyL

on 05 Nov 10As a web designer who works on various start-ups and on-going projects it can be tough and overwhelming to see the finish line. I like this approach to help setup my workflow and see project progress to show clients for their well-being as well. Win-win!

-codyL

Samdani

on 08 Nov 10Great Post. Hope to take this approach in a few situations

Nabil

on 08 Nov 10Insanely inspirational post. I’m sharing this one with friends!

This discussion is closed.