37signals and Meetup go way back. Meetup was one of our first design clients back in the day. And founder Scott Heiferman was even a guest poster for a month here at SvN back in ‘03. We’ve watched closely as Meetup has grown and evolved since then, especially during the tumultuous period after it began charging customers. It’s been almost six years since that fateful decision so we decided to sit down with Scott and talk about it.

In April of 2005, Meetup went from free to pay and started charging organizers of meetings. Many customers were outraged:

Congratulations, you’ve officially joined the “Asshole Club” along with the likes of BELL CANADA, EXON, KFC, McDONALDS, and all the other mega-corp. conglomerates who don’t give a shit about anyone or anything but lining their own pockets with money.

Others predicted the company’s demise:

I think it’s fair to say most organisers were shocked, and most of the ones I’ve spoken to will simply cease organising for their groups…There isn’t anything Meetup is doing these days that users can’t simply do on their own and more effectively, and there’s plenty of open source software to make use of and create your own website.”

Meetup wasn’t expecting the harsh response. “We were really naive,” says Scott Heiferman, founder of the site. “We figured that if people didn’t like it, they would just say, ‘OK, I’m not going to do this.’ As opposed to really taking it personally. Because this wasn’t like we were taking away their medicine. But people were so upset and we got such anger and such vitriol. The backlash was very bad. And we were surprised by that.”

According to Heiferman (seen at right in a photo by Tim Wagner), the site lost around 95% of its activity. “Now imagine you’re the hot startup – people forget we were the hot thing that was on 60 Minutes – and all of a sudden, in a flash, you see 95% of your activity go away. I mean, that’s the backlash in its most visceral form. It was like, ‘Oh, man what did you do? What do we do?’ We never really wavered seriously, but it’s a punch in the gut. It’s saying, ‘We were touching this many lives and now we’re touching not many lives, and oh, everyone hates us.’

“Now, did we think it was going to be less? No, not really. We knew. We said, ‘OK. If we get 10% or 5% to continue and pay that would be great.’ Because we were in this to make something great for people.” And Heiferman knew to do that, something had to change.

Little goes according to plan

Back in 2002, the original revenue model for Meetup was to charge venues $1 for each person brought in to a café, bar, pizza joint, bowling alley, etc. for a Meetup. “For a number of reasons it failed,” says Heiferman. “It was too early. It was hard. There was a discrepancy between the number of people who said they were going to come and who actually showed up. And too many people were going to their Meetup [at a coffee shop] and not buying coffee.”

Little was going according to plan. Heiferman explains, “Most of what we thought Meetup was going to be used for, people didn’t use it that way. And what they did use it for were things we didn’t imagine when we were building it. It never crossed our minds that this would be a political mobilizing tool.” Yet that’s where Meetup was quickly gaining the most attention. Politicians like Howard Dean embraced the tool and so did a then-unknown Illinois State Senator named Barack Obama.

At the same time, Meetup began pursuing additional revenue streams. It charged political organizations. It added AdSense. It experimented with Meetup Plus, a premium offering.

None made much of a difference though. When asked what made Meetup Plus special, Heiferman answers, “God, I don’t even remember what it got you. It got you some kind of features where you would be able to…I don’t know. I can’t remember.” Heiferman laughs and continues, “That was the problem. That’s a problem with a lot of freemium things. We refused to handicap the core, free product. So it wasn’t compelling.”

A two-headed problem

The ineffective revenue models forced Meetup to reevaluate. “It was nickel and dime stuff. We were not profitable. So, it just sort of led us down this path of asking ourselves, ‘OK, what business are we in? Who are we here to serve? And how can we establish a business model which aligns with that and get paid properly to do so?’

“I’m a believer that profitability and sustainability are important. Esther Dyson, who was one of our only angel investors and she’s on our board, made some statement way back when we started that the best investor is your customer. I really wanted to have a simple, sustainable business.”

The best investor is your customer.

There was also another huge problem facing the company. “It was way too easy to start a Meetup,” Heiferman explains. “People would be sitting in their underwear starting a Meetup about something. And then 99% of the Meetups weren’t any good. They weren’t successful. They didn’t have enough oomph put into them. The organizer wasn’t in to it.

“So imagine the user experience. You go and you sign up for a Meetup and you’re excited about it: ‘Oh there’s a breast cancer Meetup in this town.’ And then you have the worst experience. It’s just crap. There’s nothing there. Or it gets filled with spam and there’s no one curating it, no one caring for it, no one with skin in the game.

“So our biggest problem was that people would be flowing into Meetups and they would have a bad experience. So what do you do? Well, you could create all kinds of reputation or rating systems. We were trying to figure out how can we institute a quality filter here.”

The charging solution

After discussing it internally, Meetup began to feel charging could solve both the cruft and revenue problems. Meetup advisor Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, championed charging as a filter. “He would just tell us these stories of how, when eBay got going, people paying for listings was a really important quality filter. People forget that Yahoo and Amazon followed eBay and were like, ‘We’re going to crush eBay and offer a free listing auction product.’ And they both did and they both failed at the time,” explains Heiferman.

The company was also inspired by Craig Newmark. “He is our hero, in the sense of building a simple, people-serving product,” says Heiferman. “It was clear that Craigslist charging was a quality filter – when they would institute a fee in the job listing or real-estate listing, the crap would get filtered out.”

Plus, the idea of actually selling something appealed greatly to Heiferman. “I remembered after the dotcom bust around 2001, I would see these interviews with Jeff Bezos where he would be so clear about saying that Amazon is this customer-centric company,” says Heiferman. “And I was just so envious of being a part of a business where they simply got paid for a great product.

“I was coming out of the ad business [at I-Traffic] and I hated it. There was all this convoluted bullshit about affiliate networks and all this crap. I just wanted to earn a good living where there was decency.”

$19/month

So Heiferman wrote a letter announcing the new pricing model ($19/month for meeting organizers). The backlash was swift. Heiferman took the time to respond to many critics personally in forums and blog comment sections. The company also held an in-person customer Meetup to discuss the changes. Still, most of the site’s activity disappeared.

When asked if he would handle the whole transition differently if he had it to do over again, Heiferman answers, “This is going to sound terrible, but the thing I would have done differently is frankly, to have respectfully listened to everyone but, not taken the complaints too seriously.

“We have this history at Meetup, we make big bets. It’s woven into the DNA of this company that we take big bets. We do it because we have our eye on our mission, which is to see lots more Meetups happen. When things change, I think that it’s easy to get really wrapped up in the complaints.”

It’s woven into the DNA of this company that we take big bets.

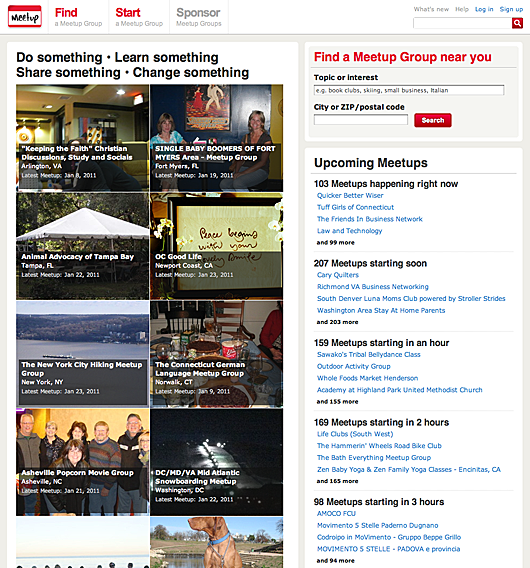

Looking back

Charging organizers eventually turned out to be a big win for Meetup. It’s now almost six years later and Heiferman reports, “We’re solidly profitable. We’re doing well. We’re always growing. 85% is us getting paid by the people who use Meetup. Yet 99% of the people who use Meetup today don’t pay us anything, and they get tons of value out of it. We think we found the right spot.”

Meetup has kept its price consistent over the years. “We just launched with a price and never changed it. You could say, ‘Gosh, you probably left a lot of money on the table by not having a small, medium, large.’ Or, ‘What is the price sensitivity? Could you charge more? Could you get higher volume by charging at different levels?’” says Heiferman. “But the DNA of this company is to kind of shun too much thinking, and focus all of our heart, soul, and energy on making the product better and better. It’s funny. An MBA would look at this place and say, ‘You have no idea where your pricing sensitivity really is.’”

Is there a victory lap mentality when he looks back at all those who critiqued the move? “Hell yeah!” says Heiferman. “Am I proud of the fact that we’re a sustainable, profitable business? Yeah. The big headline, by the way, in going from free to fee for us is: Yeah, we lost 95% of our activity but now we have much, much, more going on than we ever did before and half the Meetups are successful, as opposed to 1-2% being successful.”

Heiferman also feels charging has simplified everything the company does. “There’s so much good potential that can come out of just charging people for your good product,” he says. “And it’s a virus. It’s a disease. It’s contagious. It becomes person to person. It takes over. It’s a simplicity of organization. The most important thing is it lets you sleep well at night when you get to say that everything you do is for the benefit of the people, for the user. If you get to say that everything you do, every decision, and every operational thing you do is serving them, there’s a simplicity – and it’s just good for your conscience.”

Daryn

on 25 Jan 11Great post. It isn’t just making a decision for major change that is hard, but processing the response from your users – especially your biggest fans, who may prefer that nothing ever changed.

We (TeachStreet) made a similar free-to-paid shift last year. Here are some tips that Dave, our CEO, laid out from our learnings – including how we modified our original pivot plans based on feedback from our users:

http://techcrunch.com/2010/06/13/free-to-paid-tips/

Dave Schappell

on 25 Jan 11This is an awesome interview - specifically the point about charging for things acts as a filter - we saw the same thing with our TeachStreet class listings. From our experience (as one of the people who led Amazon Auctions!), we knew that this would happen, and planned for it - we didn’t want to turn pricing on too early, or we’d have a ghost town, but we always knew that the day would come. Those who pay actually get a better experience, because all of the free and untended listings are no longer cluttering up the space. It truly does work better for everyone (except spammers, etc.). I hope that we’re one day as successful as Meetup - the site was one of our inspirations (and was in our very first powerpoint pitch deck!).

Onward,

Dave (founder and CEO of TeachStreet)

Fred

on 25 Jan 11sooooooo … it looks like the guys at TeachStreet read SvN :D

Chris (from L.C.)

on 25 Jan 11As the organizer of local Houston Meetup chapter for a well-known open source blogging platform, Meetup has been extremely valuable at keeping us organized and on track. It’s been well-worth the measly $19, and in my opinion, worth far more.

I see many new platforms obfuscating and making their revenue models too complex. If you have to explain using more than 10 seconds, it’s likely that you need to simplify. Fortunately for Scott and Meetup, they were able to get to that point quickly. Many startups won’t, and will crash and burn.

Brad

on 25 Jan 11I’m interested to know, from people like Scott, that if they had to do it over again, do they think they would have been better off launching as a paid service right from day1? or was the free period a crucial factor in building enough recognition and momentum that you were still moving forward, even if you quickly lost 95% of that earlier momentum and had to build up again.

Ben Carlson

on 25 Jan 11I’ve been struggling with offering my latest project up for free, or pay-to-play… I’ve been reading 37s for lord knows how many years, and agree with them that you have to charge, then I started this project, and I was thinking “ad/affiliate supported, but free to the user!”

This post re-grounded me… I forget that I’m willing to pay for a good product, even if there’s a free competitor. Thanks for the reminder!

-Ben

Devlin Dunsmore

on 25 Jan 11Fantastic post! Sums up SO MANY great lessons. I’m working with 2 startups right now, one of which started 2 years ago and focused on “free” as a means to build community, the other launched 2 weeks ago with a 100% revenue driven business model.

Granted there are a lot of factors that differentiate these 2 companies (including the founding teams) but on the surface, the company offering users real value and charging for it is seeing more action in the first 2 weeks than my other startup that has been around 2 years!

Charging users isn’t the devil, you just need to charge the right price.

Amber Goodenough

on 25 Jan 11This post is so timely for me! I am launching a new app in the next month and have been going back and forth on how and what to charge for memberships, or if I should even charge. Interesting to hear that you can charge for memberships and yet 99% of the users will never pay a dime.

Thanks for the insight and sharing your experiences, it’s always helpful to hear from other companies that have struggled and succeeded.

Lara Feltin

on 25 Jan 11I remember watching Meetup in 2005 when they started charging. We followed their example for Biznik.com in 2006. I believe that one of our mistakes was that we referred to our one paid membership level (with a $10 monthly fee) as a “supporting membership”, yet we were (and are) a for-profit company. When you give your customers the impression that they’re supporting your business, you’re setting up misaligned expectations. In 2007 we added a second level at $24/month but we didn’t correct the mistake in the names until 2009 when the premium membership names were changed to “Pro” and “ProVIP”.

@Ben, there’s a lot to be said for perceived value and using fees as a filter. Just remember the 90-9-1 Principle of online communities. 1% of people create content, 9% edit or modify that content, and 90% view the content without contributing. (Our paying membership follows the same pattern.) Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1%25_rule_%28Internet_culture%29

Lara Feltin Cofounder & CEO Biznik.com

whatsthebeef

on 26 Jan 11There has been a lot of discussion about online profiteering and effective online business models with the concept of advert driven profits taking a bit of a knocking recently.

Which selection would be most profitable is obviously dependent on the type of product, demographic etc. However on a very high level, for products which aren’t so clear cut which is the most effective model, I can for see an oscillation between the quantity of ‘advertising for revenue’ and ‘charging for products’ companies. As the customer/user is engulfed by adverts the impact the adverts decrease as does the user experience the effectiveness of this model will decrease and users will start seeing the appeal in paying for products more, as I believe is happening now in some areas. As more companies are inclined to charge, adverts decrease and their impact increases, advertising space charges can increase and more companies may adopt them them.

This is obviously ignoring for now the effects of targeted advertising that may equate to brainwashing in the future and be quite effective indeed.

Andy Croll

on 26 Jan 11I guess this couldn’t go under the Profitable & Proud series… although it has the same ‘feel’.

Four rounds of funding with total value $18m. Including the bulk of that post ‘charging change’. No snark intended.

I’d be interested to hear their thoughts on whether the funding was a help or a hindrance. And whether there was a significant difference in the thought behind the early and ‘post-charging’ rounds. And whether the initial funding was the reason they didn’t start charging sooner?

Interesting article, it just opened more questions for me!

Nic

on 26 Jan 11I also read that sentence twice. I gather the 99% of users that don’t pay are folk going to meetups, not organsiers, and only organisers have to pay.

@Matt 85% of what? 85% of the growth? 85% of the fun? 85% of the staff get paid by people using Meetup?

Phil

on 26 Jan 11Awesome writeup, I remember using Meetup around that time, and initially had the same thought “Hey why pay for this, I could just organize it on a spreadsheet or something”, but Meetup did such a great job on SEO, it provided value by sending new users, so there was something worth paying for, and heck it would only cost each member $1 a meetup at most.

We use a freemium model for BudgetSimple, and while the “Plus” version isn’t acting in the same purpose of keeping out junk, it does serve as a way to add new complicated features. If enough people want a new feature, we stick it in the Plus version. That way the free one is always simple and if you want more features you go for Plus.

ML

on 26 Jan 11@Matt 85% of what? 85% of the growth? 85% of the fun? 85% of the staff get paid by people using Meetup?

I took this to mean 85% of revenue is from charging organizers (as opposed to advertising or other revenue streams).

Richard

on 26 Jan 11It’s price ELASTICITY of demand, not price sensitivity.

Ron Stauffer, Jr

on 27 Jan 11This is fascinating. I was shocked when the Meetup Group I went to was canceled after two years. I later found out it was because the organizer couldn’t make the meetings anymore, and that you had to pay to be an organizer, so she didn’t want to keep paying. If it didn’t cost anything, she probably wouldn’t have canceled the group.

The whole group fell apart, because nobody wanted to do all the work of being an organizer and paying $228/year for the privilege of doing so. I was completely surprised that you had to pay to be an organizer. It makes sense to an extent, but I don’t think anybody knows about it. I’m all for making profit, but I think they may be charging the wrong party.

The biggest mistake Meetup made (in my humble observation) was to make the switch so late in the game. Waiting until you have such a huge following and then sloughing 95% seems suicidal. And I’m really surprised that they didn’t anticipate such a backlash. There is infinite demand for that which is free. Users who pay nothing for your services generally perceive that it’s not worth paying for. So they will never convert to paying customers.

If I were running Meetup, I think I’d propose charging everybody $1-2/mo to be a part of a group and let organizers create Meetups for free, or at least give them a refund at some point. Doing so would spread the financial burden equally, and would incentivize people to organize groups. Spending $12-25/year to be a part of a good group with a solid organizer is more than reasonable.

When I signed up for my first Meetup group, there was a button to click on to donate to the organizer. I did so because I wanted to reward her hard effort in getting the group going. I had no idea it was because she was paying for the group.

Newton

on 27 Jan 11I think Today was another Bet-The Company Moment – they rolled out a complete redesign over night with out a beta and removing all the great features they once had!

After being on their boards and emailing them several bugs all AM – I see many organizers closing their meetups and moving to other platforms

This is a shame because it went from being a good looking, user friendly site to unusable overnight

Plus they don’t seem to want to listen to their paying organizers – saying it will not be changed back or modified – just deal lol

Lets see if this will make or break them like myspace I guess only time will tell Newton

Matthew "PappaSmurf" Honeycutt

on 28 Jan 11“The best investor is your customer.” Scott has already forgotten this!

Meetup.com just this morning took another big gamble by angering and disrespecting a huge portion of its 85% of income. The paying organizers, the 1% that keeps them in business. Not sure it Google bought them out or what, but Scott is in for a long week. Keep for fingers crossed but the organizers of the meetups, have now organized a dues strike! http://www.meetup.com/boards/thread/10359201

CarlB

on 29 Jan 11I had no idea meetup still existed. My local Ruby user group used it back when it first started, but it didn’t work out. Meetup sent so much spam, with no option to opt out or tone it down, that many group members, including me, completely blocked it with spam filters.

Lori Jill

on 29 Jan 11I have to agree this was a bad move on Meetups behalf. I am an organizer of 2 groups and I have only been doing it since last April. I was such a big fan that I was getting ready to start another one or two in neighboring cities. I’m now a very upset customer (yes, customer but Scott has forgotten that’s what we are when we hand him our money for a service). He was the one who decided to make this a paid service and therefore he owes his customers some level of support. We are getting non after he decided to dump this on us. I would have paid him twice the fees if he needed more revenue to keep things the way they were. I’d bet many organizers felt the same way but he didn’t even ask, he just changed everything on us in the night. Many of us woke up to Chaos. I want to know who is going to pay all my PayPal fees that I am now incurring as I refund my members money for Meetups I no longer have control over, nor opened up for them to pay. Yes, other companies are jumping on Meetups mistakes and I feel confident that they will bring more services to the table. Who wouldn’t, they have a golden ticket right now!

Anonymous Coward

on 30 Jan 11What exactly changed recently that has some people so upset? The way I read it they changed the design (a design is going to change over time). Did they change something else?

Carol Shepherd

on 30 Jan 11As a former UI beta tester: Meetup usability has gone from very good to abysmal—if you are talking about facilitating groups and group usability.

If you are looking to transform Meetup into a self-publishing events calendar funded by a corporate sponsorship model, this is the perfect way to do it. Clearly it is intentional.

Here is what I and other organizers think about Meetup’s way forward>

1) Meetup is stripping group branding and customization to switch user loyalty to the general Meetup brand.

Comments: “Does anyone truly think that Meetup sat around and thought “Wouldn’t it be great to remove people’s images that represent themselves and replace it with google maps? While we are at it let’s bury all their about pages, photos, videos, etc.”? This is intentional. They don’t want your branding.”

2) By shifting the focus away from groups to events, Meetup has transformed itself into a site facilitating self-organizers.

Comments: New “Meetups in the making” events have a very low threshold to get created (3). They want users to self-organize so organizers do not control events or groups anymore.”

3) (Fees-paying) Organizers are now glorified moderators of self-organized Meetups.

Comments: “If you disable self-organized Meetups your group page is static. Upon landing there it is a mere bulletin board of events with no group personality. The interactive group activity feed has been deliberately buried [below the fold]. It might as well not be there. If you accept self-organized Meetups you lose control of your group and the events and your role is now that of a mere moderator.”

4) These changes are to allow Meetup to accommodate corporate-sponsored events and promotional perks, which can be pushed to Meetup users directly, without the group-organization model.

Comments: “Way more money in this than in your organizer ‘dues’. Imagine restaurants, bars, hotels, entertainment venues and other places competing with you, on “your” group Meetup page, by listing their hosted events there next to yours—while Meetup collects revenue from them for access to “your” group.”

4) “Ownership” of the group function will migrate to Meetup. Being an “organizer” will become free, or they may pay you a nominal fee instead.

Comment: “They have reduced dues by 50%. They realize many organizers (who are paying for the privilege) will leave and take their groups with them. But other people will take over or recreate groups, partly for ‘perks.’ Assistant organizers were changed to regular organizers to facilitate this. They want the perks pushed.”

5) Meetup deliberately stripped group communications by removing organizer-to-member posts and moving member-to-member activity from the center “blog” of the page to below the events feed.

Comments: “They don’t want users going to a group to participate in group communications. That takes focus away from the events-only design. Meetup has the user home page where you see [a feed of recent user activity from your groups]. Is it any accident that within-group activity is now buried down beneath the fold? They know that burying it there is death for usability.”

Carol Shepherd, Attorney Arborlaw PLC

Meetup organizer for: Ann Arbor Nordic Skiiers, Ann Arbor Swing Dance Association Ann Arbor Adventurers Club

ideamonster

on 31 Jan 11Just an idea – if you want to expand to less wealthy countries you could decrease meetup planning payment for those geographic areas.

Anonymous Coward

on 31 Jan 11Just from a technical point of view the new coding is full of bugs, it has downgraded features and the new look and feel is amateurish. This change was hacked not created using modern software engineering methods. The work of script kiddies not professionals. No beta testing, no input from users etc.

Scott baby bet the farm let’s see if it works out for him.

Kat

on 31 Jan 11It’s not just a simple redesign or technical bugs. Meetup.com has eviscerated the core of how people actually used meetup, in order to create a closer relationship with Meetup Everywhere …. they thought they had a built-in international base of eyeballs for corporate sponsors. They encouraged f2f community building at the beginning and then failed to realize that the vehicle is not the community. If we leave meetup.com (which looks likelier and likelier as each day passes), our people (their eyeballs) go with us. It’s not meetup.com that is taking them out to dinner, theater, on hikes, on bike rides, and to play trivia. But hey, what can you expect from a bunch of 20 somethings playing at being executives with no real adult supervision.

Bob Carroll

on 31 Jan 11Sorry, the changes Meetup HQ made this time to the detriment of both organizers and users are far too radical to be without some financial motivation. Meetup has sold out its customers to turn its membership into pimp out tools for corporate interests.

Meetup spokespersons (when not in hiding) have stated that they are listening but it is abundantly obvious that they are not.

I’ve seen enough, I moving my groups to one of a few good alternative sites which, surprisingly enough, seem to be much more willing to make the user’s interests a high priority. Meetup has clearly betrayed its paying customers.

Yesterday I set up ex-meet-up.com to serve as a future group locator for the former Meetup groups like mine that are moving on to better pastures.

Bob Carroll – Las Vegas

This discussion is closed.