It took more than a year and three distinct attempts to get Google Docs in Basecamp ... and still, the damn thing almost didn’t get built. Why was it so hard?

We knew we needed it. Integration with Google Docs was a super-popular feature request, and usage in general is on the rise. Since Basecamp is a repository for everything project-related, it made sense to show the same love to Google Docs we show to any other type of file you can store in a Basecamp project.

Problem was, we don’t really use Google Docs ourselves. And we’re kind of notorious for scratching our own itch and not building shit we don’t need. It’s absolutely the exception that we would create a feature we didn’t plan on using. (For years, to-dos in Basecamp Classic didn’t have due dates, because we just work on things until they’re shippable. It wasn’t until enough customers hollered at us that we eventually added them.)

“We know tons of our customers use Google Docs; they have to,” says Jason Z. “Everybody’s using Google Docs. So we know it’s useful, we know people are asking for it all the time. There just comes a point where we have to figure it out.”

Shortly after launching the new Basecamp in March 2012, a small team explored what it would take to link to Google Docs from Basecamp. “We started with a little experiment to see whether the tools Google provides are enough to do basic integration,” said Jeremy, the programmer on that first spike. The goal was to be able to “pick a file from Google without having to commit to deep integration that changes the way Basecamp works.”

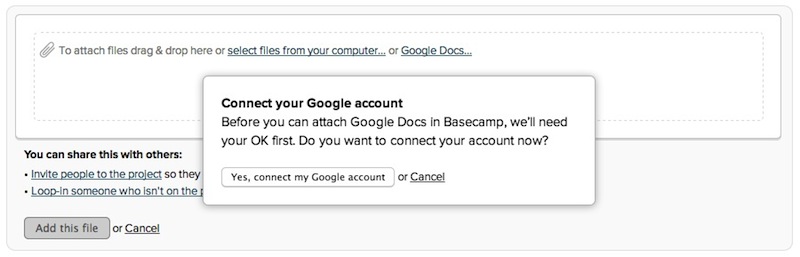

Google’s file picker made integrating with Google Docs easy, but rendered switching between accounts (if you’re signed in as one user and need to sign in as someone else) nigh on impossible. And we got hung up on what to do about permissions: Our choices seemed to be either allowing anyone who had the link to edit the document, or letting Google handle permissions and suffer the nasty flow and UI that resulted (more on that later).

With the account switching problem, our choices were to wait for Google to improve their tools, or scrap that and find some other way to integrate — i.e., roll up our sleeves and build our own picker. “That led to a waiting game,” Jeremy recalled: “if Google’s own tools got good enough that we could use them, then we’d have an easier time integrating.” So we punted.

Nearly a year later, a different group took a second look. While there still wasn’t a straightforward path for switching accounts, Javan experimented with a ton of different parameters and landed on treating authentication as a separate, first step to lead into the file picker, using Google’s JavaScript client.

Managing the two steps separately gave us the flexibility we needed to resolve the account switching issue, but the permissions demon was still rearing its ugly head. We punted again until we’d have more time to explore it.

Each time we felt like we were getting close, we’d reach the same stalemate. No one knew which of the two options for handling permissions was the lesser of two evils:

- Allow anyone with the link to view the document. This route would have meant sharing a Google Doc in Basecamp = changing its permissions so anyone with the link could view and change it. Other tools handle permissions this way; it makes things pretty easy and keeps the UI clean. But it creates a pretty gnarly security concern, in that there’s no way to revoke access later. People no longer employed at an organization might be removed from its Basecamp account, but still have access to proprietary information stored in Google Docs. Or users might share the link with outsiders who could then access and edit the document anonymously. No bueno.

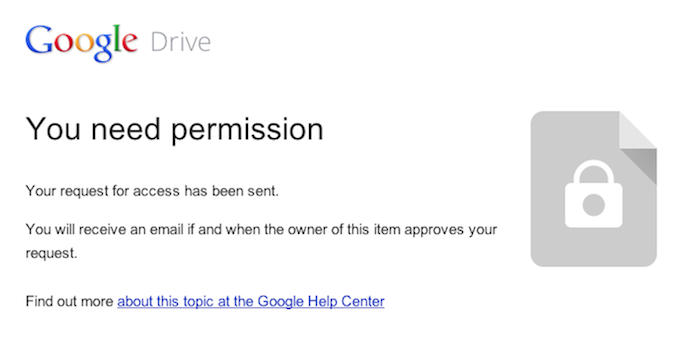

- Let Google be the gatekeeper. When permissions are set within the Google account and Basecamp doesn’t mess with them, we get to wash our hands of security concerns. Convenient for us! But it passes this potential morass of access seeking and granting onto our users: The viewer has to be signed into Google, and they need permission to view the document to see the preview in Basecamp. If they don’t have permission, they can request it through Basecamp. They’ll then be directed to a Google page, and from there, the request is emailed to the Google Doc’s owner. When the owner grants access to the document, Google sends an automated email to the viewer with a link to view it. “A lot of us were feeling like this leads to a pretty crappy experience,” Javan says, “because you click on the doc and then you hit this brick wall.”

“I was worried that people wouldn’t understand that, because I didn’t understand it,” recalls Ann from QA. “I did an experiment with the support team where I shared a Google Doc with them … I got all kinds of requests to view the document, because I hadn’t given them permission yet. I was afraid that oh my God, every customer was going to see that.” Adding a private file to a Basecamp project with 150 people on it might generate 150 email requests for access to the file. That was too big of a burden to pass along to customers.

The temptation was to punt a third time — only that was no longer an option. “We decided very clearly that if we don’t do it this time, if we don’t figure this out, we’re basically saying that Basecamp is not ever going to have this,” Jason Z. says. “Because why would we take a fourth attempt? That would be ridiculous.”

The pressure to “ship or get off the pot” led the team to explore other possibilities, like building a folder system that would copy Google Docs into a Basecamp project folder on Google Drive, or using Box.net’s Google Docs integration. We finally started to wonder whether the people who wanted Google Docs in Basecamp might already have the permissions thing dialed in. Jeremy chimed in at that point:

Companies switch to Google Apps from company Exchange email and central network fileservers. They “go Google.” Everyone at work is on Google, signed in, and has access to email, drive, calendar, contacts, etc. Google Apps recommends default sharing settings that are a lot like having a old-school central fileserver: newly created files are visible to others by default. There’s no sharing step or permissions-request dance: https://support.google.com/a/answer/60781. This is a golden path. It’s well-integrated and it’s the default when a company goes Google.

That perspective alleviated a lot of the trepidation we had about what users would see when they clicked on a Google Doc — the hope was that if people were already using Google Docs at work, they can probably already access all the links they need to be able to access by default. The access nightmare we envisioned wouldn’t occur if companies’ Google Apps admins were already setting up good defaults, the way Google recommends.

We still weren’t 100 percent convinced we had it right, but it felt good enough for v.1 — to be hands-off, and let the people who use it figure it out (with help, of course). “It’s funny how long the project went on, and in the end, it’s almost simpler than where we started,” Javan says. “But I guess that makes sense.”

“We made a bet on this permissions thing,” Jason Z. says. “We don’t use the feature, so we don’t know. We can’t anticipate what the pain points are going to be here.”

A month or so after shipping, it’s looking like we made the right bet. The majority of feedback has been of the thank-you-so-much-for-adding-this! variety. So far, 56 percent of users are logged into Google when trying to preview a document from within Basecamp, and of those, 91.5 percent already have access to the document they were trying to view. For how much concern there was over whether we were making the right call with permissions, it’s been super quiet. “We were really expecting more confusion, because we were confused,” Ann says. “The people who do use it know how to use it, and I guess we’ve fallen in with their expectations.”

“That’s a super important lesson just in product design in general,” Jason Z. concludes. “You can engineer all kinds of things, and they might be the wrong things if you don’t know. So it’s better to under-engineer and let the pain kind of bubble up organically, than to guess wrong.”

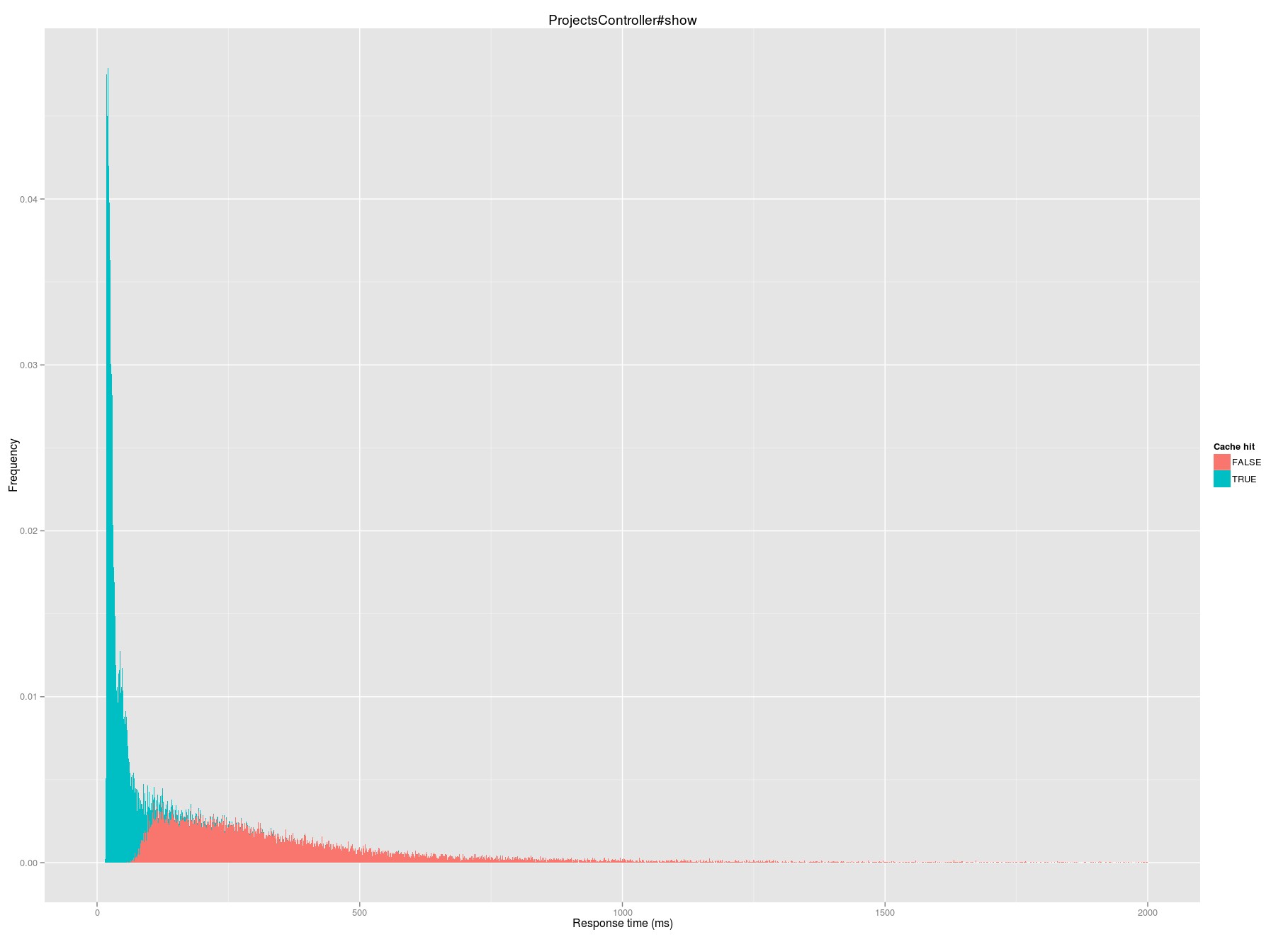

Median request time on a cache hit is 31 milliseconds; on a miss it jumps to 287 milliseconds.

Median request time on a cache hit is 31 milliseconds; on a miss it jumps to 287 milliseconds.