Mike Chang and Eric Grismer, besties since high school, had always kinda sorta kicked around the idea of starting a business.

After college, Chang left Southern California to work in Taiwan for a few years. The two friends toyed with the idea of sourcing something cheaply from Asia they could turn around and sell in the U.S., but they never landed on anything they felt passionately about.

Chang took off to earn an MBA from Oxford, and moved back in with his folks in Los Angeles after graduation. It was late 2008, and the job market was in the sewer. He didn’t have a job … and he wasn’t super convinced he wanted one, either.

“I definitely was interviewing and trying to get a ‘real’ job,” Chang says, “but I was kind of turned off by the whole thing.” He’d put on a tie, show up at networking events, shake hands, make contacts. “I felt like it was always the same boring conversations, the same small talk.” The whole situation was depressing.

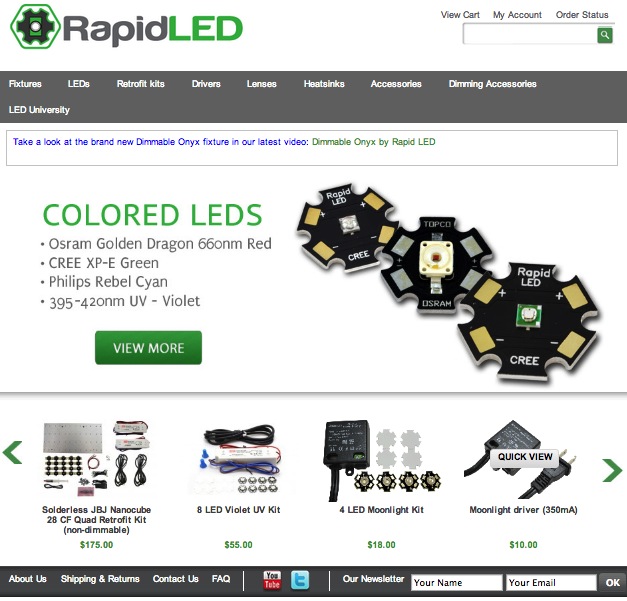

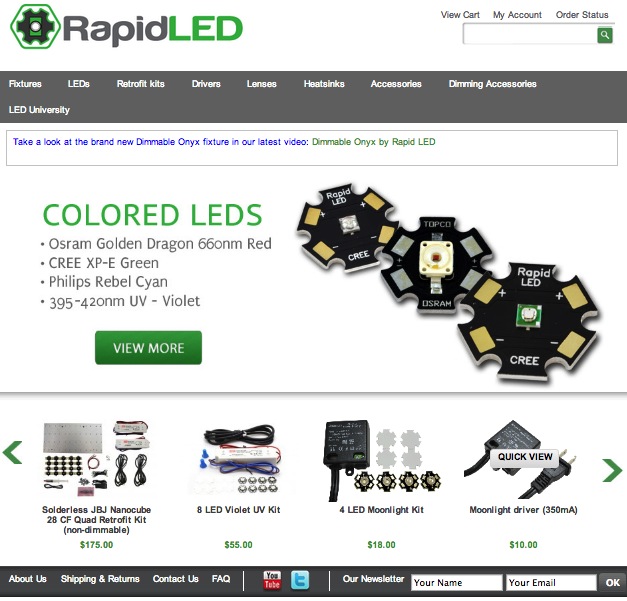

Grismer, living in Berkeley at the time, called up Chang to mention that people were starting to use LEDs to light aquariums — and was that something he could find cheaply in Asia? Grismer had been interested in fish tanks since they were kids, but Chang never got into it — it’s an expensive hobby. Still, his program at Oxford had stressed green companies, and he knew LED was the lighting technology of the future.

What the heck, they decided. Why not? The idea is kind of funny, almost. Lighting for fish tanks? Hard to get more niche than that.

“I thought it was a pretty low-risk proposition and that I was going to get a real job eventually anyway, so it didn’t hurt to start a small side business in the meantime,” Chang says. They did a little research, spoke to few contacts, found out they’d have no problem sourcing the products they needed. Chang moved to Berkeley to be closer to Grismer.

“We asked each other how much money we had,” Chang recalls. “I remember I had about $2,000 left, and Eric said he could come up with about $2,500.” That was it. They didn’t approach anyone for funding. It hardly even occurred to them.

“Honestly, I thought it was such a small niche industry that no one would be interested,” Chang says. “We didn’t think it was ever going to become anything big. We never took ourselves seriously back then, and we still don’t.”

Mike Chang and Eric Grismer in China, July 2009. “Obviously we weren’t taking ourselves too seriously at the time if we planned to leave the country only a couple of weeks after launching the site.”

Mike Chang and Eric Grismer in China, July 2009. “Obviously we weren’t taking ourselves too seriously at the time if we planned to leave the country only a couple of weeks after launching the site.”

Having less than five grand to start out with turned out to be less of a snag than the learning curve Chang and Grismer found themselves faced with: Neither was an engineer. “We had to learn it on the fly,” says Chang. “People spend years and get PhDs on light.” They tinkered with parts for months, trying to develop a ready-to-use product, but couldn’t get it right. Finally, they stumbled upon a long thread in a fish forum about assembling aquarium lighting with parts available online. That was their eureka moment.

“As soon as we saw that, we realized we had been trying to reinvent the wheel, and that all we had to do was simply sell people the individual parts and they would put it together themselves,” Chang says. Turns out fish tanks are a relatively DIY enterprise anyway — if you have one in your house, chances are you’ve already figured out how to run your own plumbing and manage other projects more complex than assembling your own light fixture. DIY kits were the way to go, they reasoned.

With that, they spent the entirety of their modest investment on their first purchase order in summer 2009 — “and to be honest,” Chang says, “if that didn’t work out we would have quit then and there.”

Quitting might have looked tempting. No one was earning a salary in those days, and Chang was sleeping on the floor in his friends’ studio apartment. “Since they were students and broke just like I was, I never felt out of place or that I really needed the money,” says Chang. It was cramped, but rent was free, and they all had fun together. He promised his roomies he’d name a product after them in return for their kindness.

“I really wouldn’t trade that for anything,” he says. “It was a good year.”

Chang took a temporary job with the U.S. Census Bureau, sold his possessions on eBay, and did whatever else he could to bridge the gap until Rapid LED started making enough money to pay him a small salary. Since the business had practically zero overhead (their storage space was a closet in the same cramped studio), they were able to pump their initial earnings right back into the business.

That worked, as did their extremely customer-focused business model. All Chang wanted to do in the early days, he says, was sit there and wait for emails to come in so he could answer each customer and take care of their needs individually. “People were just amazed at how fast we responded, and at the time we were willing to spend with them to help them pick out their product.”

“I was pleasantly surprised by how much your customers will advertise for you,” Chang says. “If you deliver them a good product with good service, it’s amazing how much people will appreciate it.” Without any money for advertising, word of mouth was all Rapid LED had to go on.

They were the first company to offer DIY lighting kits, but competitors — some of them Rapid LED’s first customers — soon followed suit. Their first-mover advantage helped them stay ahead of the pack, as did (perhaps counterintuitively) their lack of technical expertise. Since Grisman and Chang didn’t have the knowhow or equipment to test which cheaper LEDs might work, they just bought and sold the best name-brand bulbs they could.

“The quality of the light going into the fish tank really matters. People think 100 watts of light is 100 watts of light,” Chang says, but “color spectrum really matters, light intensity really matters, longevity really matters. Lighting is one of the cheaper components of a fish tank. People will have thousands of dollars of fish and coral. It’s important to get really good lighting in there because you’re keeping something much more expensive alive.”

Customers rewarded Rapid LED for its hands-on support and high-quality products by telling their friends, and the business grew organically from there. They eventually brought on a few part-time employees and one full-time customer service rep, another buddy from college. Their revenues grew from $380,000 in 2010 to $1.2 million in 2011 and $1.6 million in 2012. Projected revenue for this year is between $1.75-2 million.

Most recently, the company purchased a commercial condo in Burlingame, Calif., which they’ll move into soon. (They named the company under which their new workspace is held “SooKoo LLC,”  after the friends Chang crashed with that first year: Soohyun Cho and Peter Koo. Cho and Koo ended up marrying, and celebrated the birth of their daughter Evelyn in Dec. 2012.)

after the friends Chang crashed with that first year: Soohyun Cho and Peter Koo. Cho and Koo ended up marrying, and celebrated the birth of their daughter Evelyn in Dec. 2012.)

“Not bad for a $4,500 start,” says Chang, “but obviously we’re still looking ahead for more growth and opportunities.” Indoor and commercial lighting are more competitive markets, so the plan at Rapid LED is to look into various niche industries to see what else they can do. “Indoor growing is a much larger market than aquariums,” he says, “herbs, or whatever else you want to grow.”

Cough, cough.

“But we’re having fun and doing well now, so we don’t feel pressure to sell,” Chang says. “We’ve all been friends for so long and we started with nothing.”

“I think it’s OK to start small,” he muses. “Everyone wants to build a billion-dollar company, and they think they need to go out and find angel funding. Not everyone starts with that ability. ... Do what you can within your means, and just work hard. If I could go back and do it again, I totally would. It’s cliche, but money’s overrated.”

That attitude keeps Chang out of wearing a suit and glad-handing at networking events. “We’re in an industry where it’s pretty relaxed; it’s not fast-moving. It’s more genuine. I don’t feel like I ever come to work and have awkward conversations. Not that I’m not used to that, but it’s good not having to do it,” he says. “I’m working with my best friends every day.”

Visit Rapid LED.

“Bootstrapped, Profitable & Proud” is a Signal Vs. Noise series highlighting profitable companies with $1 million+ in revenues that didn’t take VC.

Andrea on horseback, Michael at Fulton Fit House, and Kristin in an extended side angle pose.

Andrea on horseback, Michael at Fulton Fit House, and Kristin in an extended side angle pose.

Mike Chang and Eric Grismer in China, July 2009. “Obviously we weren’t taking ourselves too seriously at the time if we planned to leave the country only a couple of weeks after launching the site.”

Mike Chang and Eric Grismer in China, July 2009. “Obviously we weren’t taking ourselves too seriously at the time if we planned to leave the country only a couple of weeks after launching the site.”

after the friends Chang crashed with that first year: Soohyun Cho and Peter Koo. Cho and Koo ended up marrying, and celebrated the birth of their daughter Evelyn in Dec. 2012.)

after the friends Chang crashed with that first year: Soohyun Cho and Peter Koo. Cho and Koo ended up marrying, and celebrated the birth of their daughter Evelyn in Dec. 2012.)