I actually think that there was always an unsustainable feel about what had happened on Wall Street over the last 10, 15 years, and it’s not that different from the unsustainable nature of what was happening during the dot-com boom, where people in Silicon Valley could make enormous sums of money, even though what they were peddling never really had any signs it would ever make a profit.

That doesn’t mean, though, that Silicon Valley is still not a huge, critical, important part of our economy, and Wall Street will remain a big, important part of our economy, just as it was in the ’70s and the ’80s. It just won’t be half of our economy. And that means that more talent, more resources will be going to other sectors of the economy. And I actually think that’s healthy. We don’t want every single college grad with mathematical aptitude to become a derivatives trader. We want some of them to go into engineering, and we want some of them to be going into computer design.

About Matt Linderman

Now: The creator of Vooza, "the Spinal Tap of startups." Previously: Employee #1 at 37signals and co-author of the books Rework and Getting Real.

How much is watching TV costing you?

People who spout off about how they don’t have a TV always remind me of The Onion’s “Area Man Constantly Mentioning He Doesn’t Own A Television.”

But the #1 reason people have for not doing what they want to do is time. The refrain: “There just aren’t enough hours in the day.” And yet these same people manage to veg out in front of the TV (the average person now watches 4.5 hours of TV a day).

“How Dumping TV Allowed Me to Quit My Job, Create an Online Business and Fund My Retirement Account” gives the actual financial costs of watching TV:

It’s amazing the amount you can accomplish when you find an extra 3,285 hours to work on something you enjoy doing rather than vegging in front of the TV. Those hours helped us create a small network of websites and blogs which allowed both of us to quit our jobs and work on them full time a couple of years ago…

To put it into perspective, if you watch an average of 31.5 hours of TV each week (which the average person in the US does) and you value your time at minimum wage of $5.85 an hour, you are spending nearly $800 a month ($798.53) to watch TV. That comes to nearly $10,000 ($9582.30) a year. I would imagine that most people reading this value their time well above minimum wage, so the cost is likely several times that number. When you look at it from that perspective, watching TV is an extremely expensive and financial draining habit to have.

Seeing the costs broken down like that really shines a light on the problem. Life’s about priorities. If there’s something you want to be doing, ask yourself how much your TV viewing is getting in the way.

Choose your tube

The article above also offers some good tips on how to get your TV watching down. Something that’s worked great for me: I moved recently and didn’t get cable at my new place. My viewing is now limited to things I choose to watch on Hulu, Netflix, and YouTube.

The choosing is the key there. It means I have to actively pick things to watch instead of just flipping through whatever’s on. As a result, I watch way less TV overall. No more SportsCenter highlights, no more local news, no more American Idol. Before, I’d get swallowed up in any/all of those and realize hours had just slipped away. That’s no longer an issue.

Finding more hours

While I’m on the subject, another great way to deposit some hours in your free time bank: Don’t commute. Obviously it’s not an option for everyone. But if there’s a way you can work from home, even if it’s just a day or two a week, think of the extra time you’ll have that you usually spend in traffic, on the train, etc.

An hour here, an hour there. It starts to add up. Then you can use that time to build something on the side. A few hours a week on a project will tell you if you’re onto something. You’ll know if you love doing it. You’ll know if others care at all. Then you can decide if it’s worth throwing more hours at or if it was just a fun thing to try. Either way, you didn’t have to quit your job or do anything too risky.

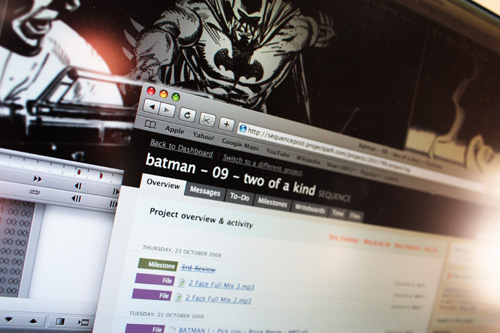

How Sequence brings "Batman: Black & White" to life using Basecamp

We usually publish product case studies exclusively over at the Product Blog but this one is so cool we wanted to share it here too…Sequence, an animation and design house with a strong focus on motion comics, has been working on a series of “Batman: Black & White” short form digital motion comics. The team there runs productions using Basecamp for project management and internal reviews of quicktimes/audio asset sharing/shot animation assignment. Sequence’s Ian Kirby tells us more below.

When your company consists of just a few people, a daily chat is all that’s needed to keep everyone up to speed. However, when a company grows to 10 or so people in a very short time, keeping everyone on the same page is easier said than done (especially when the workload is heavy). Enter Basecamp.

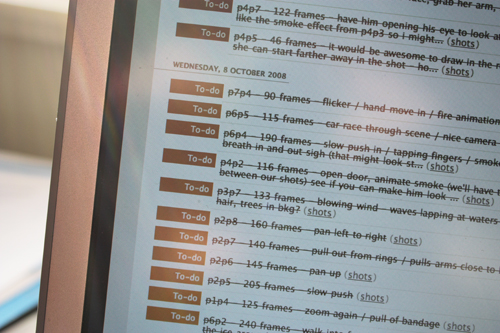

The Batman Black and White motion comics started with flat artwork scans – we literally received scanned comic books. That’s it. Our artists take these pages and break them apart, separating characters from backgrounds, redrawing scenery, extending frames to fit a 16×9 aspect ratio for HD delivery, etc.

Preproduction, flattened artwork is brought into Avid and timed with dialogue. We do a locked timing pass so that music can be scored and each shot (panel) can be given animation direction and duration – this is where we really rely on Basecamp.

Each shot’s page and panel number is entered in the Basecamp to-do list along with, again, a frame count and direction. Depending on workload of other projects, shots might be assigned to ‘Sequence’ or to specific animators. If a shot needs 3D, or has heavy facial animation, they’ll be assigned to the animator most fit for the job. We all have our strengths.

Continued…Ready, aim...fail: Why setting goals can backfire

“Although simple numerical goals can lead to bursts of intense effort in the short term, they can also subvert the longer-term interests of a person or a company – whether it’s a pharmaceutical firm that overlooks safety in the rush to get a drug approved, or a dieter who resumes smoking to help lose 20 pounds. In work requiring a certain amount of creativity and judgment, the greatest risk appears to lie in overly simplified goals. Reducing complex activities to a bundle of numbers can end up rewarding the wrong behavior.”

The big problem with plans and goals: They lock you in. You put on blinders. You stop improvising. You don’t change direction. That’s bad, especially if you’re a company that needs to improvise and change with the times.

The word entrepreneur and its baggage

The term entrepreneur feels outdated. It’s associated with people who work brutal hours, invest their life savings, and risk it all on a dream.

But these days, you can do a ton with just a little. You can build a business by working just a few hours a week. You can keep your day job and start something on the side. Software and technology that used to cost a ton is now free (or very cheap). You can easily work from home and/or with people thousands of miles away.

In this new landscape, people who would never think to call themselves “entrepreneurs” are out there starting businesses, selling products, and turning profits.

Take Markus Frind. He works a maximum of 20 hours a week yet runs one of the largest websites on the planet (PlentyOfFish.com, a dating site) and pays himself more than $5 million a year.

Jason Kottke and John Gruber are writers who work from home on their own terms. Their blogs have built huge audiences with revenues to match. And they’ve done it without asking anyone’s permission, finding a publisher, or signing a distribution deal. That would have been impossible 10 years ago.

Soniei, profiled here, is a painter from Nova Scotia who sells directly to customers through eBay, Etsy, and her web site. She makes a decent living, loves being able to work on whatever she feels like working on that day, and says she can’t imagine doing anything else.

Beth Terry sells and ships toys under the name Iron Chick’s Toys (see this PDF). A few years back, she would have had to rent out a warehouse and hire people to fulfill orders. Now she uses Amazon.com’s fulfillment service to do it for her. Instead of sending 50 boxes to individual buyers, she sends just one box of 70 items to Amazon. Instead of spending thousands on storage, she spends just $60 per month. Not bad when you consider she’s selling an average of $900 a day (with sales that increased at least 25 percent month over month during her first year).

These people are thriving without risking it all or leveraging their lives. They’re succeeding without MBAs, business plans, and all those other credentials you’re supposed to have before starting a business. You just don’t need that stuff to build something great anymore.

It’s time to get over the idea that risk and reward are so intertwined in business. And maybe we need to come up with a better term than entrepreneur to describe this new group of people out there building businesses. Any suggestions?

As a political pollster, I always observed that the poll that often got the most coverage was the one that was different from the others, regardless of whether it was right, or whether the pollster had any track record. This is true with opinions, too: those on the extreme right or left, or those that are the most titillating, seem to drive the most traffic through their sites. The center doesn’t seem to have either the edge or the passion to grab the same kind of traffic.

Mark Penn, former advisor to the Clintons and Tony Blair, in America’s Newest Profession: Bloggers for Hire

A graphic novel inspired by noir film directors

Finding fresh inspiration [SvN] advised looking to a different medium for inspiration, the way Tony Bennett imitated musicians rather than other singers.

Another example to add to the list: Hannah Berry’s debut graphic novel, Britten & Brülightl (she spent 2.5 years hand-painting each panel of the story). In this interview, Berry explains how she used cinematic influences to guide her work on the novel. [via Flavorpill]

Being a film geek, illustrational challenges were tackled with cinematic elements, often with a nod to directors I really rate (I’m thinking in particular of ‘neo-noir’ types like David Fincher, Christopher Nolan and the Coen brothers, and ‘old-school noir’ Carol Reed). It’s probably not ideal – I know I’m not using comics to their full potential while I’m echoing film, but it’s a good place to start.

A recurring problem while working on the book was finding ways of illustrating dialogue that are animating but unobtrusive. I love writing dialogue, and I tend to write staccato conversations that cross backwards and forwards a lot, which for the sake of the format I have to edit down pretty heavily. To save the scene from getting bogged down in words I had to introduce some level of movement, and as movement is obviously something that’s lacking from the comic world, I needed to compensate in other ways. A lot of the films of Jeunet and Caro (especially Delicatessen) use composition and angle to make static shots appear quite dynamic, and theirs sprang to mind as a good example to follow.

Turning to film influences to get ideas for a graphic novel is a great example of how a different medium can provide inspiration. Whatever you’re working on, using different influences than the rest of the pack is a great way to sound like an individual instead of just a member of the chorus.

Check out a couple of pages from the book after the jump.

Continued…J. Peterman: Selling stories, not just products

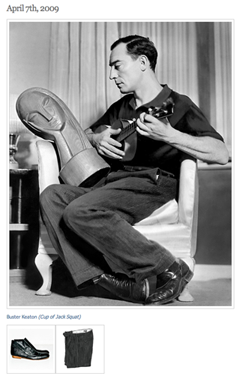

Nerd Boyfriend is surprisingly compelling. Pictures of vintage “nerds” along with links to buy modern-day versions of what they’re wearing. (Like Buster Keaton, right, wearing corduroys along with a link to get a similar pair at J. Peterman.) It feels like a peek at the future of clothes shopping — a way to nail the sensibilty of clothes through personality.

Nerd Boyfriend is surprisingly compelling. Pictures of vintage “nerds” along with links to buy modern-day versions of what they’re wearing. (Like Buster Keaton, right, wearing corduroys along with a link to get a similar pair at J. Peterman.) It feels like a peek at the future of clothes shopping — a way to nail the sensibilty of clothes through personality.

Speaking of The J. Peterman Company, it’s a great example of a company that has used storytelling to set apart its products (long before it was hip to do so too).

Sure, the descriptions are silly — to the point where it became a running gag on Seinfeld. But that’s part of the charm. Like the hand-drawn illustrations instead of actual photos. It’s setting its own tone that is a world away from department store genericness. Some examples below.

Italian Shirttail Dress (aka Ms. Indiana Jones):

Continued…

At the Colosseum in Rome, the toe of your sandal kicks over a chunk of marble, revealing a mint silver denarius from the reign of Emperor Hadrian.

Dinner at La Pergola is on you.

Then, there’s that innocent stroll into the jungle during your stay at an eco-resort in Belize.

Next thing you know, you’ve discovered the fabulous lost city of Xupu Ha…dozens of acres of temples and statuary and steep-sided sacrificial lakes, concealed by centuries of vines.

Your Mayan is rusty, but the natives seem to refer to you as “She Who Has Bows on Her Sleeves.”

Italian Shirttail Dress (No. 2318), found by serendipity in Florence. Upper-calf cut of soft, pre-washed linen, fashionable and favored by adventurers who want to keep cool. Rounded shirttail hem. Self belt. Point collar.

Bust darts, shaping seams, and those bow-tie roll-up sleeve tabs eliminate any possible confusion with Mr. Jones.

The difference between truly standing for something and a mission statement

Being an opinionated company is great. Great companies have a point of view, not just a product.

But there’s a world of difference between truly standing for something and having a mission statement that says you stand for something. You know, those “providing the best service” statements that are created just to be posted on a wall. The ones that sound phony and disconnected from reality. The ones that come off like a press release, not an actual directive.

For example, let’s say you’re standing in an Enterprise rental car office. The room’s cold. The carpet is dirty. There’s no one at the counter. And then you see a tattered piece of paper with some clip art at the top of it pinned to a bulletin board. And it’s a mission statement that says this:

Our mission is to fulfill the automotive and commercial truck rental, leasing, car sales and related needs of our customers and, in doing so, exceed their expectations for service, quality and value.

We will strive to earn our customers’ long-term loyalty by working to deliver more than promised, being honest and fair and “going the extra mile” to provide exceptional personalized service that creates a pleasing business experience.

We must motivate our employees to provide exceptional service to our customers by supporting their development, providing opportunities for personal growth and fairly compensating them for their successes and achievements.

And it drones on. And you’re sitting there reading this crap and wondering, “What kind of idiot do they take me for?” It’s just words on paper that are clearly disconnected from the reality of the experience.

It’s like when you’re on hold and a recorded voice comes on telling you how much the company values you as a customer. Really? Then maybe you should hire some more support people or offer email support so I don’t have to wait 30 minutes to get help. Or just say nothing. But don’t give me an automated voice that’s telling me how much you care about me. It’s a robot. I know the difference between genuine affection and a robot that’s programmed to say nice things.

Standing for something isn’t just about writing it down. It’s about believing it and living it.

Go Ahead, Steal Me

Author Jonathan Lethem sold movie rights to two of his books which never got made. Disappointed, he started the Promiscuous Materials Project where he publishes short stories online and invites filmmakers and playwrights to adapt them. He asks for only a $1 fee and that he get credit as author of the source material. It’s gotten results too; Filmmakers are now at work on adaptations of his stories. Smart move by Lethem to realize letting go of his copyrights is smarter than protecting them at all costs. If a movie or play based on his material takes off, so will his book sales.