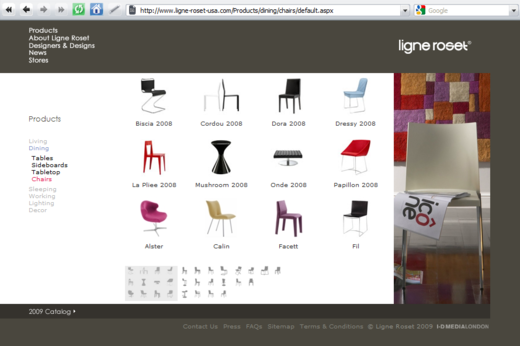

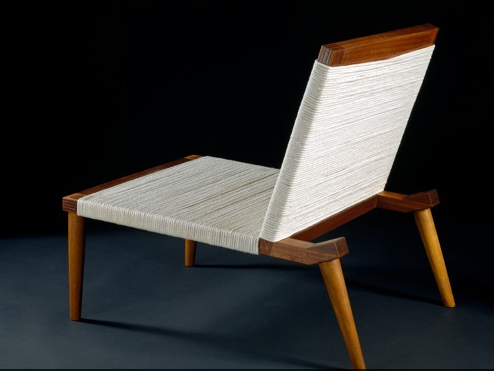

Sam Maloof is “America’s most widely admired contemporary furniture craftsman.” He’s 93 and still going strong. Here’s a slideshow of his work.

He doesn’t take measurements before he starts a project.

I do not feel that it is possible to make a working drawing with all the intricate and fine details that go into a chair or stool, particularly. Many times I do not know how a certain area is to be done until I start working with a chisel, rasp, or whatever tool is needed for that particular job.

For him, functionality trumps aesthetics.

Continued…My goal is to make furniture that people can be comfortable living with. If you’re not preoccupied with making an impact with your designs, chances are something that looks good today will look good tomorrow…

I try to make my things aesthetically pleasing; but, if it isn’t functional, people will ‘oo’ and ‘aah’ over it in an exhibit but they won’t buy it. … My feeling is a chair has to be functional and comfortable for tall and short alike.