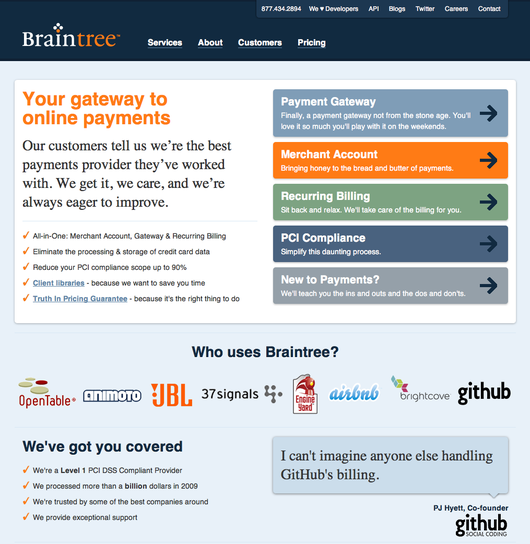

Braintree’s Bryan Johnson will answer your questions in the comments section.

In 2003, Bryan Johnson (right) was hired for a commission-only job selling credit card services to businesses. “I was broke,” says Johnson. “The job was brutal. Business owners were tired of the industry’s deception and trickery and didn’t hesitate when given an opportunity to vent.”

In 2003, Bryan Johnson (right) was hired for a commission-only job selling credit card services to businesses. “I was broke,” says Johnson. “The job was brutal. Business owners were tired of the industry’s deception and trickery and didn’t hesitate when given an opportunity to vent.”

Johnson quickly excelled, though. He became the top salesperson out of 400 nationwide and broke the existing sales record during his first year. His secret? “I simply figured out that businesses were looking for thee things: honesty, education and reliable service. I filled that gap and was received warmly. I also worked my tail end off.”

But by 2007, Johnson was sick of working for a big corporation. He says, “I concluded that I’d rather live poor and hungry than work in a large, bureaucratic and political environment where I personally couldn’t see how my efforts created value.”

He started figuring out what it would take to do his own thing. “I figured that I needed to make at least $2,100 a month to leave,” he explains. “My wife and I had learned to live quite frugally. I had started a few other businesses before, so this uncertainty and financial risk was something I was accustomed to. I had a single objective: Get back into the saddle. I was going to do whatever it took to get there.“

He took a few days off work and flew out to Utah, where his old customers resided. He asked them if they’d switch their processing to his new company, Braintree. Quite a few of them did, collectively generating $6,200 a month. Braintree was officially up and running.

Premium, not freemium

Early on, Johnson decided to stay away from the freemium model so popular among tech companies. “My experience in the payments industry told me it wasn’t for Braintree,” he explains. “We offer exceptional service during the sales and application process that continues after a merchant is set up with us. This level of service is too costly for a free account.”

So Braintree went the opposite route and charged a premium. It started with a $200 monthly minimum, which it’s since lowered to $75. “At $200, our minimum was 4 to 8 times higher than our competitors,” says Johnson. “Applying a floor helps the right kinds of customers self-select our services. After all, we’re as interested in having the right customers as they are in having the right provider.”

Who are the customers Braintree decided to write off? “It was a fool’s errand to try selling medicine to those who hadn’t yet experienced pain. Payment processing is complex. It’s difficult for inexperienced merchants to recognize value. We’d spend countless hours trying to explain ‘pain’ and our cure but some just didn’t care because they hadn’t felt it yet. With our limited resources, we had to figure out a way to work only with those who valued the medicine we were offering.

“We did take some grief for our higher minimums, but when we did, we’d politely explain that there were other, less expensive options in the industry, which may have been a better fit. I think staying firm often created an inverse effect, causing people to value us more than they did initially.”

Revenue growth

The formula is working so far. In 2010, Braintree generated $4.5MM in revenue, grew from 15 to 24 employees (now over 30), and doubled its customer base, according to Johnson. It powers payments for companies like LivingSocial, Github, OpenTable, and Animoto. And 99% of its customers come through word-of-mouth. “We’re on track to do $8 or $9 million in revenue during 2011,” Johnson says. “We also expect to rank among the top 50 on this year’s Inc. 500 list.“

Johnson is quick to note the difference between Braintree and other emerging payment companies. He says, “Four of these companies have raised around $40 million each and have roughly 3-6 times the personnel we do.”

Johnson feels that necessitates a different approach. “For many, raising a lot of money is accompanied by baked-in assumptions for how a business should be built,” he says. “The playbook typically calls for a large executive team and a few layers of management, which is very expensive. I think VC-funded companies are more inclined to throw money and people at opportunities and problems. This approach works for some, but there are other ways to build a successful business. Growing on our own dollar has granted us the freedom to do what we want, when we want, and how we want.”

It also forces Braintree to embrace constraints. “Without outside capital, we have to make do with less,” says Johnson. “Constraints are a beautiful thing because they force creativity and precision. We don’t have the resources to throw after hit-or-miss hires or strategies. Bootstrapping a business requires a different mentality. It’s taught us to be frugal, hire slowly, and exercise caution as we grew the business. While companies that take funding can do those things, people have a tendency to behave differently when it’s not their money on the line.”

“People have a tendency to behave differently when it’s not their money on the line.”

More than revenue matters

Braintree avoids chasing revenue simply for revenue’s sake, according to Johnson. He explains, “We believe that success is also measured by what our customers say about us, how people feel about working at Braintree, and how our contributions are making the industry a better place.”

Focusing too much on revenue can be dangerous, he believes. “That pursuit can take on a life of its own and — if left unwatched — can undermine the very things which made you successful in the first place. I think there is a great lesson in The Little Shop of Horrors,” he explains. “After conceding just a single drop of blood, Seymour’s peculiar plant begins a radical transformation from cute to terrifying. In the end, the beast’s insatiable thirst costs Seymour everything, drawing his brutal demise. In a similar way, chasing revenue at the expense of other values is a slippery slope fraught with danger.”

The Braintree office.

The Braintree office.

An insane industry?

Braintree is also trying to improve what Johnson sees as “an unscrupulous and broken industry” that he says lacks sanity, fairness, and transparency. Credit Card Data Portability is one especially sticky area. “Just as you couldn’t transfer your phone number before 1996’s Telecommunications Act, payment providers had been holding customers’ stored credit card data hostage,” he says. “To address this significant problem, we created a Credit Card Data Portability Initiative and wrote an open letter to the CEOs of two big providers, inviting industry cooperation. Many industry insiders initially dismissed the effort, but, in the last 90 days alone, we’ve worked with every major provider to facilitate a data transfer to us.

“The issue is important to us because first, it’s the right thing to do. Second, we are the newcomer and the little guy – relatively speaking – and are therefore at an unfair advantage when existing merchants working with large, incumbent competitors want to switch to us. The size and scale of our competition has, in the past, allowed them to throw their weight around and hold data hostage, simply to avoid competing on merit alone.”

An eclectic office

Braintree has an eclectic office in Chicago that consists of two large, open rooms, and pixelated old-school Mario decals on the walls. There are no offices, no managers, and no dividers. “It does occasionally get chaotic, but it’s a trade-off we make for collaboration and enjoyment,” says Johnson. “We all make an effort to spend time together outside of work. We eat lunches together, have events at each other’s houses, and organize outings for everything from cooking classes to concerts. We also organize and pay for after-work activities, such as Whirley Ball and Bulls’ games. We try to do one per month.

Establishing crystal clear expectations: We try to bare it all because we’ll be waking up together for some time. For example, in our job postings we have a section titled, “What you would have done last month had you been with us” (which can include as many as 30 bullet points). We also have a “DO NOT APPLY if…” section, which we believe speaks louder to those we’re targeting than those we’re trying to deter.

Requiring a “connection” to ensure they “get us”: We look for people who jump out of their seats to say, “This is what I’m looking for!” We expect this to happen because we send enough smoke signals in our job posts to connect with people on meaningful levels. We want passionate people who care deeply about their work environment and value the same things we do. Lukewarm applications don’t survive.

Predicting future behavior with past experience: Trusting good intentions or best guesses is worse than flipping a coin. Our belief is that past performance is the best predictor of future success. We want all the context and details of an applicant’s prior work experience.

“For us, ‘culture’ is the totality of social behavior, beliefs, thoughts, work, and organization. It’s not created from a company retreat and it doesn’t take shape from a vision statement. Instead, we treat it as a living organism – the sum of all inputs.”

Hiring challenges

It hasn’t been all smooth sailing though. “Hiring has been our most difficult challenge,” says Johnson. “We’re extremely picky about who we hire, and we’re growing so fast that we’ve been treading water to keep up. We used to hire when it hurt, but have since adjusted to stay ahead of the curve wherever possible.

“We’re not only fanatical about hiring the right people, but about determining if they’re the right fit once they join. Fits and misfits are readily identifiable. A bad hire can’t be swept under the rug or ignored because they can’t be sent to a different department or overlooked.”

Braintree’s advice

These days, there’s lots of talk of “following your passion.” But can you really be passionate about credit card processing? “I’m not particularly passionate about payments, but I am passionate about trying to build a good company,” says Johnson. “I tell entrepreneurs to ask themselves ‘What do you think about when you are not required to think about something else?’”

Johnson also advises starters to be wary of trends. “It’s easy to get caught up in the latest fads, what’s considered ‘sexy,’ and those getting all the attention today. Chasing these things can—at times—be right on, but they can also be a fool’s errand. Often, the best alternative is simply finding and solving an old, boring problem.”

Visit Braintree.

This is part of our “Bootstrapped, Profitable, & Proud” series which profiles companies that have over one million dollars in revenues, didn’t take VC, and are profitable.

David Andersen

on 08 Mar 11“These days, there’s lots of talk of “following your passion.” But can you really be passionate about credit card processing? “I’m not particularly passionate about payments, but I am passionate about trying to build a good company,” says Johnson.”

Thanks for saying that out loud.

Rishi

on 08 Mar 11I met Bryan at a conference a few years back when BrainTree was just getting started. He asked me if I would switch from PayPal to BT. I told him we are pretty small and can’t afford the time and cash to do it. He then proceeded to ask me what he could help out with, and I said we could use some introductions to investors. He then spent the rest of the conference introducing me to investors (even ones that he never met before). Congrats Bryan and BrainTree!

Tony Ford

on 08 Mar 11ArtFire.com switched to Braintree last year for our subscription processing. We get calls and have offers to pay less to other companies and have not even thought of moving.

The service, attention to our customer status, and support at Braintree are fantastic. Our developers love their API and I love that I can email on a Saturday night with an issue and have a qualified tech respond in minutes.

Braintree even proactively notifies me of any issues that might have affected me, even the ones I never would have known about. That raises the bar in their industry beyond what most payment companies can reach.

Like Braintree, Artfire is bootstrapped, profitable and proud of building something focused on lean and sustainable business rather than VC in and cashing out. This article reinforces that moving to partner with Braintree was the right decision for us.

Iain Dooley

on 08 Mar 11Urr, that’s annoying. Well, the above quote was what I was referring to in my original question …

From that it sounds as though you’d already built Braintree while working at your old sales job! Is that the case? Or were you doing “pre-sales” of a product that didn’t exist yet? I’d love to hear more about your experiences prior to the ”$6,200/month” and immediately after that.

Cheers, Iain

Sawyer Bateman

on 08 Mar 11Great story! At a company I worked for years ago we handled dozens of merchant accounts/gateways for web clients, so I know the pain of dealing with these incumbents! I love that you guys are being straightforward and fair – first and foremost.

Do you have any plans to support micro-transaction sized payments (such as for online games) in the future?

Marios Lublinski

on 08 Mar 11Great story Bryan, as we all know working hard and carrying about customers will get you far. I am using Paypal now but soon will switch to Braintree.

Bryan Johnson

on 08 Mar 11@ Iain – I founded Braintree after the sales job was over and didn’t speak with my former customers until the non-compete agreement with my old company had expired. When we first started, we were focused on the service around merchant accounts.

Stinky

on 08 Mar 11I thought it was bad form to “steal” your former employer’s customers?

condor

on 08 Mar 11All the articles in the series have been great, but I’ll say this one is the best!

Bryan Johnson

on 08 Mar 11@ Sawyer – there is a dedicated cemetery in the payments industry devoted to companies that have pursued micro-payments. The economics make it very difficult because the bank fees are relatively high and unfriendly to small amounts.

Scott

on 08 Mar 11“I’m not particularly passionate about payments, but I am passionate about trying to build a good company,” says Johnson.”

Scott

on 08 Mar 11^^^^ Amen to that!

Sean

on 08 Mar 11How did Braintree create such a great credit card processing gateway so quickly? Didn’t it cost a ton of money to build that system? How does a company of ~20 people maintain and support such a system while also focusing so intently on customer service and sales? It seems like there’s a lot of technology involved, but this article did not cover that.

Matt

on 08 Mar 11@Stinky He waited until after the non-compete. Also, I don’t think it’s a black-and-white thing. If you’re working for some monolithic company that is offering its customers mediocre product and/or bad service, I wouldn’t hesitate to pilfer their clients if I had something better. If it was a mom-and-pop shop that he was taking customers from, I’d be more troubled.

Richard

on 08 Mar 11Hmmm… I don’t think I’d want to work in that office. Shoulder-to-shoulder workers? That was a joke from the 90s body shops.

Bryan Johnson

on 08 Mar 11@ Sean – We’ve run very lean. We have no managers and no executive team, just 32 very capable doers. We generated enough revenue from selling merchant account services to fund the gateway development. Our first customers were brick and mortar merchants who didn’t need any technology.

Mike

on 08 Mar 11We just switched to you guys a week or so ago after using PayPal Pro, Merchant One, and Authorize.Net over the years.

I love you guys!

Dan Manges

on 08 Mar 11@ Richard – This is Dan from Braintree. We actually choose to work this way. We’re a highly collaborative team, and although there are many ways to collaborate, we do it by working in a single open team room. We pair program for all of our development, which is why people are so close. We connect two monitors, keyboards, and mice to a single Mac Pro that the pair works on. The duplicate peripherals allow us to work comfortably while sharing a computer. The layout inspires casual conversation that leads to a great team dynamic.

Andrew

on 08 Mar 11@Bryan Johnson – Good thing your team is physically lean. Buy some more desks. I work for a company with half your turn-over (and half the staff) and we can afford desks and more office space.

Andrew

on 08 Mar 11Just saw Dan Manges comment. Fair enough if all the staff are happy with that arrangement!

Mat

on 08 Mar 11I’d love to learn more about how Braintree got started. Bryan, were you involved with development or was that done by someone else?

Bryan Johnson

on 08 Mar 11@ Mat – I am not a developer but couldn’t be happier with our CTO Dan Manges and our awesome development team.

pbreit

on 08 Mar 11I suspect they will get steamrolled by Square.

Bryan Johnson

on 08 Mar 11@ pbreit – we actually don’t compete against Square.

Kevin Bombino

on 08 Mar 11When I first started my company in 2007, Bryan took the time to explain to me on the phone about how most providers use “nonqualified rates” to scam extra money (sometimes as much as 2% per transaction) out of merchants who don’t know any better.

I’m really happy he did—we’ve saved a ton.

Furthermore, as a company who produces shopping cart software, we know first hand how often different payment gateways go down (customers typically blame us first, so we’ve built a system to let them know when the problem is actually with their gateway). We’ve never seen Braintree go down.

John

on 08 Mar 11Its business. Besides, if they were happy at Brian’s former employer, they wouldn’t have left.

per wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_technology_officer): Chief Technology Officer (abbreviated as CTO), is an executive-level position in a company.

So you do have an executive team? I am confused.

Kay Patel

on 08 Mar 11I agree with the sentiment that companies that raise money get to pick strategies and can write off bad apples. But some companies that raise capital don’t that. Look at box.net for example, they have raised around $75 million to date and without that boost i don’t think they would have been able to get that kind of attention from users and the press.

Raising money has a lot to do with the reasons. I would raise money if i am trying to perfect a technology ( if i am not savvy enough to develop it fully) and further to develop infrastructure or do marketing.

In Mr. Johnsons case, its quite clear that he didn’t need to raise money. A couple of reasons:

1. He already had experience about what he was doing from the ground up. So he knew about the technological, legal, marketing challenges and could take care of it himself.

2. He didn’t need that much money to get started. Some industries such as healthcare will need you to get your technology certified before you can even begin to market.

If the above-mentioned reasons weren’t existent, they would probably have to raise money.

Do you agree Mr. Johnson?

Dave Naffziger

on 09 Mar 11Great post, thanks a ton for sharing your story.

We’ve grown to the point where we now feel many of the pains associated with a poorly designed backend (auth.net) and likely expensive merchant account, and are just about to actively pursue alternatives.

Your post was hands down (and likely unintentionally) the best sales pitch I’ve heard in this industry.

Tim Jahn

on 09 Mar 11I love this Bootstrapped series, glad to see more stories.

Bryan and company are a great bunch. I had the opportunity to interview Bryan a few months ago about his management style.

Bryan is a great example of somebody who hustled, worked hard, and built a real business from the ground up. There’s a reason his customer base consists of the names it does. Keep up the hard work Bryan! And Matt, Jason and team, keep up the bootstrapped stories.

Dan Manges

on 09 Mar 11@ John – This is Dan from Braintree. What Bryan meant is that we built Braintree up to this point without a traditional executive team (COO, CFO, VPs, etc.). This approach allowed us to keep costs down during the early years. I’m much more of a doer than a manager and would be described equally well without the title.

Bryan Johnson

on 09 Mar 11@ Kay – that’s correct. We didn’t need much money to get started and built the business with cash flow.

James

on 09 Mar 11At one of my previous jobs back in 2009, which was a subscription start-up, we started out using Auth NET but found their API to not be so great especially for subscriptions and I reached out to Jenna and told them that we needed to be setup ASAP with a new processor. Within a few days we were up and processing; not only did they go out of their way to help us get setup, we were able to get very competitive rates.

The good service didn’t stop after we were signed on, their IT team was very helpful and responsive to our needs.

Unfortunately that company is no longer in business but I have no doubt that we would still be using BrainTree today.

Tony Alexander

on 09 Mar 11My company (TravelersJoy.com) is in the process of switching to BrainTree this week. The referral came via word-of-mouth. It’s nice to read a bit about the company that will process our payments, especially when their values coincide so closely with ours. Having bootstrapped Traveler’s Joy with my partners, I can relate to everything in this post. Great job Bryan!

Erik

on 09 Mar 11I’d love to use Braintree but my business is located outside the US (in the EU) and we cannot guarantee the requirement of 3 million in volume in 12-18 months (hard to guarantee for a startup). I’m left with dealing with EU providers with far less elegant APIs.

Les

on 09 Mar 11@Bryan, I really wished someone in the UK would step up to the plate and make a great system, and educate like you do. We’re stuck with some pretty hideous implementations (Sagepay, Paypal, Worldpay etc).

Have you guys got plans to expand into the UK (I see you only support high volume international origin)? Or can you recommend anyone this side of the pond?

Ram Kasi

on 09 Mar 11Very inspiring!! all the best Bryan and Brain tree team.

David O.

on 09 Mar 11Wow, I think this is one of the best, if not the best of the B.P.P. series. It was very educational and insightful.

Bryan Johnson

on 09 Mar 11@ Les – we currently don’t have any plans to expand into the UK as we have our hands full here in the U.S. I wish that I could recommend someone to you but we’re just not that familiar with the providers there.

Jon Mills

on 09 Mar 11Good on you Bryan that is what I like to see and hear. Success stories of people who have got off their ass and have established a quality service or product. Success to you and yours!

Nathan

on 09 Mar 11Your work environment is interesting – working in one big room, shoulder to shoulder, even using the same computers! I know 37 also advocates good collaboration between workers but this seems completely opposed to their premise that to get more done you need to have long periods of solitude.

Scott

on 09 Mar 11Bryan,

What books do you recommend?

John

on 09 Mar 11@Dan,

Thanks, I was a little confused. I looked over your offerings last night and forwarded it to my partners. I really like your transparency for this industry.

Athanasios Papagelis

on 09 Mar 11This post was inspiring through several angles.

CC processing is one of the major hurdles of modern web services and being able to tackle them as transparently as possible give us one less problems.

Still, located in Europe I can not share the joy. Everything seems to go global except payments :) Do you know any similar service for Europe (or even better do you plan to offer Braintree here as well?)

Tim

on 10 Mar 11Ability to use BT outside the US (e.g. in AU) would be handy

Good article. There is real value in follow up comments from the business owners.

+1 the closeness in the office, what if someone is a loud cougher, or constant sneezer, or is sick (some people at least in Aus, won’t stay home if they’re sick which annoys me to buggery).

Tim

Stuart

on 10 Mar 11I had a look at BrainTree for AU usage too but looked like it was overly complicated to get the required accounts to make it work.

One of the things I liked about them was the openness & “developer” feel of it all (rather than the corporate “we’re going to take all your money” feel that you get from PayPal).

Stu

Paul Montwill

on 10 Mar 11Every bootstrapped company you write about emphasizes the fact that the profit never comes first.

Dany Pink who spoke on TED confirms with researches that creative people are not driven by money. Financial incentives cause even the opposite result from expected. http://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_on_motivation.html

Also, managers who are focused on building value are perceived as true leaders and not just guys looking for a paycheck.

Digital Age is fantastic for small companies with creative and innovative people on board that solves problems.

Good luck, Bryan.

Paul Montwill

on 10 Mar 11Bryan, how long time did it take you to build Braintree before pitching to the first clients? Did you do that in evenings while working 9-5?

Bryan Johnson

on 10 Mar 11@ Paul – about 4 months. Yes, I did everything on nights and weekends until I pulled the trigger and took a few days off work to meet with my former customers to get things started.

Bryan Sebastian

on 10 Mar 11Bryan, glad you spell your first name correctly :)

I would guess that the business you are in requires a significant amount of legal work. This is one area I have never been able to figure out how to reduce costs easily. Legal bills always seem to be large. Are there any tips or advice that you have for reducing legal overhead? Or this one area you never want to look to do cheaply?

Tadas

on 10 Mar 11Bryan’s picture in the article is really weird. At first I thought it was two pics, but then the bottom one didn’t make sense…

Bryan Johnson

on 11 Mar 11@ Bryan – I suppose, fortunately or unfortunately, I’ve worked with enough attorneys over the years that I can now generally discern the efficient from inefficient and the good from the bad. It just comes with time and is costly to figure out. My test is 1) how fast they can get to the heart of the issue 2) how long it takes them to complete the work and 3) how well and they can explain complex topics. Then you can evaluate their billable rate in context of that knowledge. I realize this advice is of limited value because judging on those criteria requires comparison data.

For Braintree, we use a 20 year industry veteran who has seen it all and excels at the items listed above. He’s impressively efficient and good. I worked with two other attorneys with industry experience before I settled on him.

At any rate, I feel your pain!

Walt

on 11 Mar 11Does Braintree and 37signals have any kind of business relationship?

TJ

on 11 Mar 11In the picture their office looks VERY crowded and uncomfortable…

Dan Manges

on 12 Mar 11@TJ – This is Dan from Braintree. We actually choose to work this way. We’re a highly collaborative team, and although there are many ways to collaborate, we do it by working in a single open team room. We pair program for all of our development, which is why people are so close. We connect two monitors, keyboards, and mice to a single Mac Pro that the pair works on. The duplicate peripherals allow us to work comfortably while sharing a computer. The layout inspires casual conversation that leads to a great team dynamic.

insurance policy software

on 13 Mar 11I agree that people have the tendency to do that but what are the alternatives?

DHH

on 13 Mar 11Walt, we are very happy customers of Braintree.

Kristopher Murata

on 13 Mar 11As a programmer, I’m still curious on how much time and effort took BrainTree first version to be released.

I know that just one or two programmers would do the job fairly fast with a guy (Bryan) that knows the business logic from inside out.

Did BrainTree development was finished at the point he talks to the first costumers or it was built on the first months after that (funded with $6,200/month)?

And, really nice job with BrainTree, I’m a happy costumer too.. :)

Bryan Johnson

on 14 Mar 11@ Kristopher – that’s great to hear! Thank you for choosing us. We didn’t start building our products until after we started the business and had cash flow from selling merchant account services. Our very first customers referenced in the article (the $6,200 in monthly revenue) were brick and mortar businesses that used their existing credit card terminals. Payments, security, compliance and reliability are very complex. It took a considerable amount of effort.

gigi

on 14 Mar 11Online payments are still cumbersome, When we will have a better paypal, something that allows you to set your bank account, integrate their api and that’s it?

Now you need to setup a merchant account, a payment gateway, send a lot of docs, be pci compliant and lots of boring stuff and pay lots of big fees.

I hope that soon real competition will hit this market so that will be easier and cheaper for online business to accept payments.

This discussion is closed.