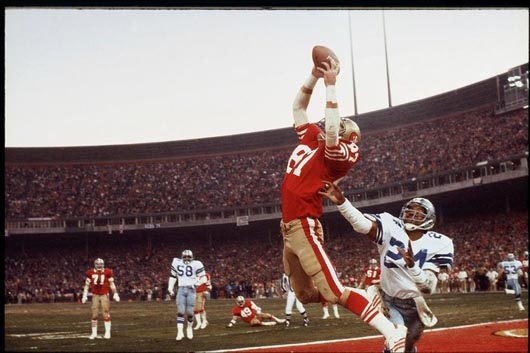

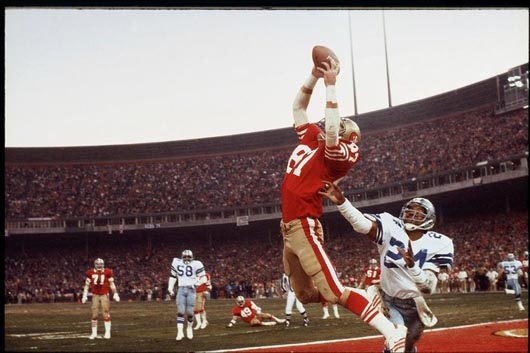

Digital Journalist has a great collection of photos from Sports Illustrated photographer Walter Iooss along with explanations of how he got the shots. Neat backstory to this photo of “The Catch” (Joe Montana to Dwight Clark TD pass in 1982 Championship Game), the most famous picture he’s ever taken.

Walter Iooss Jr. had set up in the end zone and snapped a soaring Dwight Clark in what has become one of the magazine’s enduring images (as the abundant yellow stickers on the slide attest). Iooss’s picture, though, was the result of more than positioning. He’d been shooting the beginning of this play with a telephoto lens, but as he saw the action coming his way, he quickly switched to a camera around his neck with a 50-millimeter lens, better suited to close-up action. He framed the moment perfectly.

In the Digital Journalist piece, Iooss explains why the Clark shot is one he never wanted to happen.

What’s ironic about this picture, which came to be known as The Catch, is that I never wanted it to happen. I had been covering the Dallas Cowboys the entire NFL season. I was given total access: the locker room, the trainer’s room, the off-limits spots where no photographer had been before. I’d seen the things the Cowboys did so they could play in pain. I’d become friends with one player who, the first time I was in the locker room, came up to me and said, “I want you to take a picture of me getting a needle in my shoulder.” I looked around, thinking maybe I was being put on, and said, “You’re kidding, right? Why would you want me to do that?” He said, “Because I want to give it to my son to make sure he never plays football again.” On the day of this game the same player said, “I don’t know what to do. My knee is in such pain, my shoulder is in pain, but I can’t take two shots. It’s too much. I don’t know which one to take.” With 58 seconds left in the NFC Championship Game, Joe Montana rolled out to my left and launched a pass. Something to my right came into my peripheral vision, and I reached for my camera with the 50mm lens, trying to focus. I just started hitting the motor drive and shot. Dwight Clark caught the ball probably 20 feet away from me. The 49ers scored the touchdown that sent them to the Super Bowl and the Cowboys’ season was over. I was heartbroken. I had spent a whole season with the team and had gotten close with the players. I went in the locker room after the game and the mood was as if somebody had lost their family in a car crash. In a single moment my whole story went down the tubes. But the shot of Clark catching the touchdown pass ran on the cover of SI and became the most famous picture I’ve ever taken.

Related: Sports Illustrated has a new book called Slide Show:

The thing about slides, beyond the obvious that you could touch them and hold them up to the light, was that you could scribble notes on them. You might use the slide mount to jot down a quick description of what’s happening in the photo. You could give the mount a return to stamp, if you were messengering the slide across town in those days before e-mail…These artifacts of a rapidly receding era of magazine publishing brim with a found beauty; a humble cardboard square somehow fuses a photographic moment with its slowly accumulating embellishments of history.

See slides from the book.

If you go to a cocktail party where everyone is a stranger, the conversation is dull and stiff. You make small talk about the weather, sports, TV shows, etc. You shy away from serious conversations and controversial opinions.

A small, intimate dinner party among old friends is a different story, though. There are genuinely interesting conversations and heated debates. At the end of the night, you feel like you actually got something out of it.

Hire a ton of people rapidly and a “strangers at a cocktail party” problem is exactly what you end up with. There are always new faces around so everyone is unfailingly polite. Everyone tries to avoid any conflict or drama. No one says, “This idea sucks.” People appease instead of challenge.

And that appeasement is what gets companies into trouble. You need to be able to tell people when they’re full of crap. If that doesn’t happen, you start churning out something that doesn’t offend anyone but also doesn’t make anyone fall in love.

You need an environment where everyone feels safe enough to be honest when things get tough. You need to know how far you can push someone. You need to know what someone really means when they say something.

If you have to hire, hire slowly. It’s the only way to avoid winding up at a cocktail party of strangers.

Are you giving employees time to play? Often, that’s when breakthrough ideas happen.

It’s something Jim Coudal has mentioned before — how he actually encourages employees to goof around. I asked him to expand on that and here’s what he wrote:

Most of the smart, creative, successful people I know spend a good deal of time looking for inspiration, tracking down ideas and doing research.

We do all those things too, we just don’t have a problem with calling it what it is, “goofing around.”

Play is essential, it’s through play that you find connections between things that might not be at all obvious through logic or practicality.

If you don’t have any accidents how are you ever going to have happy ones?

3M gives all employees 15-20 percent free time to work on their own projects. If it’s a success, the project can be spun off into a new business and the employee who originated it is given an equity share. Most of the inventions that 3M depends upon today came from this free time.

In 1968, 3M employee [Art] Fry was singing in the church choir and got annoyed that his bookmark kept falling out of his hymnal. “It was during the sermon,” Fry remembers, “that I first thought, What I really need is a little bookmark that will stick to the paper but will not tear the paper when I remove it.” Fry wondered whether it would be possible to create a repositionable bookmark that would stick only gently to a page. In the months after his church choir daydreaming, he spent his side-project time researching what would ultimately become the adhesive behind the hugely popular yellow Post-it Note. It was an unexpected, even random, invention that saw the light of day thanks to 3M’s flexible employee policy.

And you’ve probably heard about how Google offers engineers “20-percent time” so they’re free to work on things they’re passionate about. One interesting side effect of that is a more long-term view. People who are given free time often see further down the road since they’re not forced to focus on immediate problems.

IBM also gives lab researchers time to experiment and play. In fact, that’s how IBM invented the application of laser for eye surgery. A group of IBM scientists were experimenting with laser for improving IBM products. One scientist wanted to see what the effect of laser would be on a cut on his finger. Intrigued by the results, the scientists experimented on cows’ eyes and eventually human eyes. IBM eventually licensed out the technology, making millions in profit.

If you want breakthroughs, then give people some freedom.

Busting your ass planning something important? Feel like you can’t proceed until you have a bulletproof plan in place? Replace “plan” with “guess” and take it easy. That’s all plans really are anyway: guesses.

So next time you’re working on a business plan, call it a business guess. And that financial plan? It’s a financial guess. Strategic planning? Call it with it really is: a strategic guess. 5 year plan? You mean 5 year guess.

There’s nothing wrong with guessing, dreaming, or predicting, but it’s not planning. Planning’s too definite a term for most things. We often use planning when we really mean guessing. And what we call it has a lot to do with how we think about it, do about it, and devote to it. I think companies often over think, over do, and over devote to planning.

So next time call a plan a guess and just get to work.

Good lesson learned while working on the new book: Sometimes writer’s block isn’t really writer’s block, it’s just typer’s block.

See, you’ll be talking about an idea and nail it. But then when you sit down and try to type it out, it just doesn’t come out right. You dance around the idea. Words get in the way of what you’re trying to say.

A solution that’s worked for us: Record the conversation where you get it out right. When you speak an idea, it engages a different part of your brain than when you write it. You often say it clearer when you’re just riffing aloud. And you get to more gut-level stuff too. You bypass that “should I say this?” filter. You get it straight from your gut/brain instead of your fingers.

When you’re done recording, transcribe the good parts of what you said and use that as the foundation. Usually, it’ll come out a lot more plain-spoken and conversational. That’s a good thing too.

It might seem like a waste of time to do that talking/recording/transcribing process, but it’s not when you compare it to rewriting the same few paragraphs 5+ times.