Great speech on the need for a rockstar environment, not just rockstars. (See also Average environments beget average work and B- environment merits B- effort).

About David

Creator of Ruby on Rails, partner at 37signals, best-selling author, public speaker, race-car driver, hobbyist photographer, and family man.

Cabin fever

Hell might be other people, but isolation sure ain’t heaven. Even the most introverted are still part of Homeous Socialitus Erectus, which is why prisoners fear The Hole more than living with other inmates. We’re simply not designed for a life of total solitude.

The occasional drawback of working remotely is that it can feel like you’re surrounded by plenty of people. You have your coworkers on instant messenger or in Campfire, you receive a constant deluge of emails, and you enjoy letting the trolls rile you up on Reddit. But as good as all that is, it’s not a complete substitute for real, live human interaction.

Fortunately, one of the key insights we’ve gained through many years of remote work is that human interaction does not have to come from either coworkers or others in your industry. Sometimes, even more satisfying interaction comes from spending time with your spouse, your children, your family, your friends, your neighbors: people who can all be thousands of miles away from your office, but right next to you.

But even if you don’t have friends or family nearby, you can still make it work; you’ll just have to exert a little more effort. For example, find a co-working facility and share desks with others in your situation. Such facilities can now be found in most larger cities, and even some smaller ones.

Another idea is to occasionally wander out into the real world. Every city, no matter how small, offers social activities to keep you sane and human, whether it’s playing chess in the park, finding a pickup basketball game, or volunteering at a school or library on your lunch break.

Cabin fever is real, and remote workers are more susceptible to it than those forced into an office. Fortunately, it’s an easy problem to address. Remote work doesn’t mean being chained to your home-office desk.

This essay comes from the Beware The Dragons chapter in our new book REMOTE: Office Not Required. The book is being released October 29, 2013.

Rally cry for sinking companies: “All hands on deck”

HP has joined Best Buy and Yahoo! in an attempt to turn back the clock on remote working. Like the other two wounded, flailing giants, HP undoubtedly yearn for the late 90s, when they all were flying high. But reenacting the work principles of decades past is not likely to make mana rain from the sky again.

Neither is the hilarious corporate doublespeak that’s being enlisted to make the case. Here’s a choice bit on just how important employees are to the Vapid Corporate Slogan of The Day.. uhm, I mean HP Way Now:

Belief in the power of our people is a core principle of the HP Way Now. Employees are at the center of what we do, we achieve competitive advantages through our people. HP has amazing employees who are driving great change.

So we have great people, but we can’t trust them to get anything done unless we see butts in seats from 9-5? Who cares whether all these great people have designed a lifestyle around not having to commute long hours or live in a given city. That’s all acceptable collateral damage in the “all hands on deck” playbook for sinking companies.

Here’s a few thoughts: Perhaps HP isn’t sinking because Jane works from home, avoids the commute, and has more time to spend on hobbies and family? Perhaps HP is sinking because of strategic and managerial mismanagement? Perhaps morale won’t actually improve until the beatings stop?

It’s sad when you see once-great companies reduced to this smoldering mess of mistrust and cargo culting. But hey, at least we know now the pitch of the whistle that says its time to abandon ship. It’s “all hands on deck”.

Rethinking Agile in an office-less world

Much of agile software development lore exalts the virtue of in-person collaboration. From literal stand-up meetings to at-the-same-desk pair programming. It’s an optimization for the assumption that we’re all going to be in the same place at the same time. Under that assumption, it’s a great set of tactics.

But assumptions change. “Everyone in the same office” is less true now than it ever was. People are waking up to the benefits of remote working. From quality of life to quality of talent. It’s a new world, and thus a new set of assumptions.

The interesting, and tricky, part of choosing a work pattern is comparing these different worlds. What’s the value of a group of people who a) can only be picked from amongst those within a 30-mile radius of a specific office, b) who have to deal with the indignity of a hour-long daily commute, c) but who’s Agile with that capital A?

Versus a team composed of a) the best talent you could find, regardless of where they live, and b) who has the freedom to work their own schedule, c) but can’t do the literal daily stand-up meeting or pair in front of the same physical computer?

Obviously we’ve made our pick, and the latter setup won by a landslide. But it also made discussions about methodology more complicated.

When you’re talking to someone who thinks that the world is already defined by that first “everyone in the same office” assumption, they’ll naturally champion the hacks that makes that setup more workable. Without necessarily rethinking the overall value of the advice outside that assumption-laden context. Local maxima and all that.

It’s time for a reset. We need the same care and diligence that was put into documenting the agile practices of an office-centric world applied to an office-less world. There’s a new global maxima to be found. Let’s chart its path.

Worse is human

Before getting my driver’s license, I remember thinking manual gearboxes were an anachronism. Why on earth would someone want to row their own gears when automatic boxes could do it for you? Because it’s worse, and worse is charming.

This affection for worse repeats all over. People buy and adore expensive Swiss mechanical watches, even though a cheap Swatch will keep time better and requires no maintenance. Range-finder cameras take fiddling to adjust focus that auto-focus cameras have long since obsoleted. Vinyl records and tube amps still have lots of hardcore fans.

We come up with all sorts of justifications for this affection for worse. Manual gearboxes give you more control. Mechanical watches are about the craftsmanship. Range-finders have great image quality in a small package. Vinyl on tube sounds warmer. It’s mostly bullshit. Endearing bullshit, but bullshit nonetheless.

My pocket psychology take is that we love anachronisms because they’re imperfect. Like humans are imperfect. We form relationships with people who are flawed all the time. Flaws, imperfection, and worse are all part of the human condition. Tools that embody them resonate.

It’s hard to engineer this, though, but it’s worth cherishing when you have it. Don’t be so eager to iron out all the flaws. Maybe those flaws are exactly why people love your product.

Ambition can be poison

In the right dose, ambition works wonders. It inspires you to achieve more, to stretch yourself beyond the comfort zone, and provides the motivation to keep going when the going gets tough. Rightfully so, ambition is universally revered.

But ambition also has a dark, addictive side that’s rarely talked about.

I just finished 2nd in the ultra-competitive LMP2 category of the greatest motor race in the world: 24 hours of Le Mans. That’s a monumental achievement by almost any standards, yet also one of the least enjoyable experiences I’ve had driving a race car — all because of ambition.

Armed with the fastest and most reliable car, the best-prepared team, and two of the fastest team mates in the business, it simply wasn’t possible to enter the race with anything less than the top step of the podium in mind. Add to that leading much of the race, and a storming comeback to first position after my mistake, it compounded to an all-out focus on the win and nothing but.

That’s exactly the danger of what too much ambition can do: Narrow the range of acceptable outcomes to the ridiculous, and then make anything less seem like utter failure. It’s irrational, but so are most forms of psychological addiction. You can’t break the spell merely by throwing logic at it.

There’s not a graceful way to process this “loss”. Society generally only accepts the notion of “overly ambitious” when there’s a demonstrably large gap between perceived ability and desired outcome. In those cases, though, it’s much easier to shake off reaching for the stars and failing. That’s expected.

But when the ambition is cranked up to the max due to prior accomplishments and success, it can easily provide only pressure and anxiety. When that’s the case, winning isn’t even nearly as sweet as the loss is bitter. When you expect to win, it’s merely a checked box if you do — after the initial rush of glory dies down.

Over-dosing on ambition isn’t just an occupational hazard of sports. It goes for all walks of life. I’ve met many extremely accomplished people who’ve had the grave misfortune of reaching one too many of their goals, only to be saddled with an impossibly high baseline for success. It’s devoured their intrinsic motivation, leaving nothing but an increasingly impossible search for another fix of blow-it-out-the-park success. When that doesn’t happen, the withdrawal is a bitch.

This experience has been a painful realization of everything that Alfie Kohn wrote about in Punished by Rewards and a reminder of the wisdom of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow. Happiness doesn’t lie in the fulfillment of the expected. Neither in all the trinkets and trophies of the world. It’s in enjoying the immersion of the process, not the final outcome.

Google uses Big Data to prove hiring puzzles useless and GPAs meaningless

The New York Times has a fascinating interview about using Big Data to guide hiring and management techniques with Google’s VP of people operations, Lazlo Bock. Two things in particular stood out.

First, “On the hiring side, we found that brainteasers are a complete waste of time”. I couldn’t agree more.

Second, “One of the things we’ve seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.’s are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless”. This ties in well with rejecting the top-tier school pedigree nonsense and downplaying the benefit of formal education altogether. On the last point, Lazlo notes: “What’s interesting is the proportion of people without any college education at Google has increased over time as well”.

But beyond that, the interview is full of good tips on management as well. Especially around figuring out who’s a good manager and how they can improve. If that’s a subject you’re interested in, checkout our newly launched Know Your Company.

Apple: The organizational Rorschach

As we watched Apple unveil iOS7, the 37signals Campfire room quickly turned to awe of what they had achieved. A redesign so shocking and deep bestowed upon a product so popular left many mouths agape. Whether you happened to like the final product wasn’t as relevant as marveling at the vision, drive, and sheer determination to pull it off.

Apple has a way of making people feel like that.

But what followed next is at least as interesting: We all sought to explain just how they did it. Is it all Ive’s eye? Is it that they explore more ideas than anyone else? Is it never accepting “good enough”? Forgoing customer input and trusting their own instinct? Hundreds of triple-A designers and developers?

There were lots of suggestions. But stepping back a meter or two, it was clear that we all simply reached for our own grandest ambitions and rebranded them Apple’s secret sauce. Theorizing why Apple is able to do what it does is an organizational Rorschach.

That doesn’t make it a useless exercise. Au contraire. It just makes it more about you than them. It lets you tease out your goals and aspirations for your own work and process. It’s a kick in the ass to marvel at greatness and think of reasons “why are we not as awesome as that?”.

An organization as rich and storied as Apple has a thousand reasons for why it got to where it is. Pinning it on any one answer is futile, but it’s sure to spark a healthy debate. Indulge.

Beyond the default Rails environments

Rails ships with a default configuration for the three most common environments that all applications need: test, development, and production. That’s a great start, and for smaller apps, probably enough too. But for Basecamp, we have another three:

- Beta: For testing feature branches on real production data. We often run feature branches on one of our five beta servers for weeks at the time to evaluate them while placing the finishing touches. By running the beta environment against the production database, we get to use the feature as part of our own daily use of Basecamp. That’s the only reliable way to determine if something is genuinely useful in the long term, not just cool in the short term.

- Staging: This environment runs virtually identical to production, but on a backup of the production database. This is where we test features that require database migrations and time those migrations against real data sizes, so we know how to roll them out once ready to go.

- Rollout: When a feature is ready to go live, we first launch it to 10% of all Basecamp accounts in the rollout environment. This will catch any issues with production data from other accounts than our own without subjecting the whole customer base to a bug.

These environments all get a file in config/environments/ and they’re all based off the production defaults.

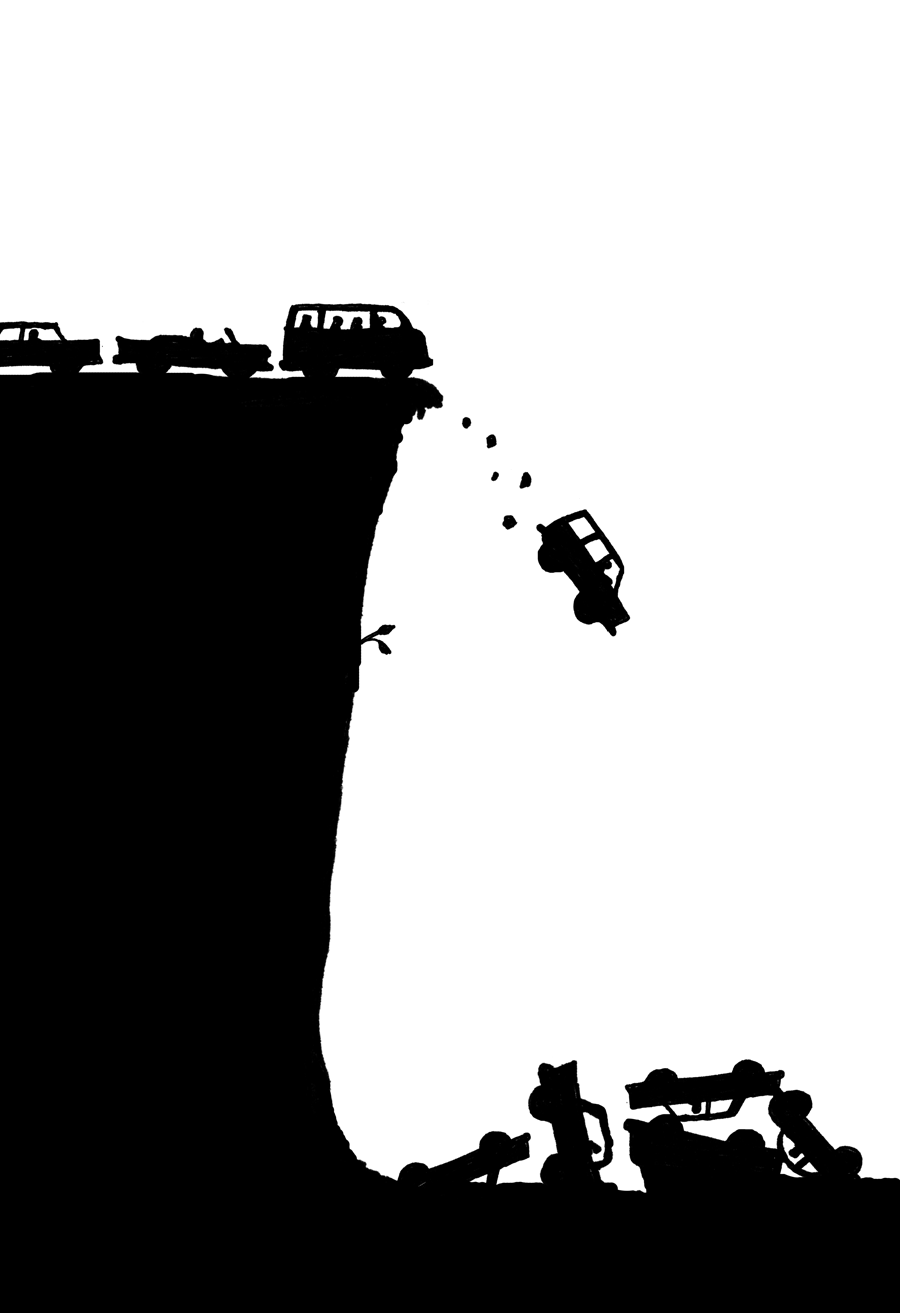

Illustrations for REMOTE: Office Not Required are being done by the fantastic Mike Rohde again. This one is for the essay “Stop Commuting Your Life Away”. The book is due out in October of this year.