Would you hire the last Delta representative you spoke with if you owned a customer service company?

First question in the Delta Airlines customer service follow-up survey. Love it.

You’re reading Signal v. Noise, a publication about the web by Basecamp since 1999. Happy !

Would you hire the last Delta representative you spoke with if you owned a customer service company?

For years I’ve chatted with smart, ambitious people and friends who want to start new projects or businesses. Often their visions are big. So they dream up equally big things their startups need: money, connections, resources. And that’s where they get stuck. They don’t have any of those things.

In 1978, an artist named Patricia came home to her husband and announced she quit her job at a newspaper. She just couldn’t stand it anymore. Occasionally, she’d have some of her art posted on the front page, which was great. But most of the time, the job was corporate tediousness.

Patricia’s husband Mel understood. He was a writer at the same newspaper. Sometimes he’d get an interesting assignment, but often he was stuck writing obituaries.

There was just one problem. He was sitting at home waiting to tell her the exact same thing. He had quit that day too.

Patricia and Mel were now both unemployed with little savings. To make ends meet, they took up freelance magazine assignments. But the income wasn’t consistent, and they could barely make rent.

They couldn’t stand working for someone else. But they couldn’t make enough money freelancing.

So, they decided to start a clothing store. But all they had in capital was next month’s rent, $1500. Could they start a store with this? Not likely. They sought out a bank loan. They were turned down. So how do they get past this?

The Oakland A’s have one of the lowest budgets of any baseball team in the United States. The owner’s cheap. Their stadium sucks. Fan attendance is terrible. If you’re going to see a game near Oakland, folks just go watch the Giants in San Francisco.

To make matters worse, back around 2002, the big teams with huge budgets kept scooping up their best players. The A’s couldn’t compete with the New York Yankees or Boston Red Sox who had a 100 million dollars to spend on players vs. the A’s 40 million.

To everyone’s surprise though, the A’s started winning games. A lot of them. The 2002 Oakland A’s won just as many games as the Yankees did that season. And the A’s put up streaks like 16-1 in June 2002, and ended the season with 20 wins in a row, one of the longest winning streaks in baseball history.

The A’s success was made famous in Michael Lewis’ book, Moneyball, and the Hollywood movie with the same name starring Brad Pitt. Moneyball publicized the strategy the A’s general manager, Billy Beane, used to win games.

He used statistical analysis, or Sabermetrics as it’s known in baseball, to find players that were overlooked by other teams. Players that might not look like typical all stars but somehow got on base a lot. He looked for old players past their prime. He even learned from statistics to avoid high school players traditional scouts valued. Sabermetrics showed that high school players’ performances weren’t a good predictor of Major League success.

Using these new analytics, they found cheap players who, in aggregate, replaced the numbers they lost when their stars joined other teams.

But something happened after the book came out in 2004. The A’s started losing again. Why? The competition started copying them. Other teams were now hiring their own statisticians, even stealing members of Billy’s management staff. The Red Sox hired the inventor of Sabermetrics, Bill James, and with their own Sabermetrics-created team and huge budget, the Red Sox won the 2004 World Series.

In response, Billy Beane started backing off of some of the things he’d learned from Sabermetrics. Since other teams were now avoiding high school players, those players became undervalued. In 2006, Billy spent his first two draft picks on high school kids. And that season he started winning again, taking the division and the first series of the playoffs.

And just like any ultra-competitive market, things changed again. The A’s found themselves losing their advantage and having to innovate.

In 2012 and 2013, Billy was on top once again, and the A’s won their division and made it to the playoffs. This time Billy was using less Sabermetrics and more an approach of: find cheap resources, configure them in different ways, and see what works.

Ted Baker, a professor at Rutgers Business School, argues in his paper, Winning an unfair game, The Oakland A’s weren’t successful because of statistical analysis. They were successful because of bricolage.

Bricolage is the construction of something new from a diverse range of available things – often cheap because people take them for granted or consider them garbage.

Billy Beane was assembling teams from garbage. No one wanted Scott Hatteberg after he was cut from the Rockies in 2002. He was a catcher who couldn’t throw because of an injury. Garbage. But Billy put him at first base where he didn’t have to throw and they could still take advantage of his great hitting.

Sean Doolittle is another example of a player who played first base but now wasn’t any good as a hitter because of an injury. So Beane gave him a shot on the mound in 2012 to see if he could go back to being a pitcher (which he played in high school and some of college). He turned out to be their best relief pitcher.

Sabermetrics helped Billy in 2002 and 2003, but when everyone started using it, what was once undervalued went up in price. So he looked for other ways to assemble cheap resources, often thrown away by other teams as garbage, until he found a new, valuable combination. That was always his game.

Patricia and Mel were stuck. They couldn’t afford to manufacture new clothes. So they bought surplus shirts for almost nothing. The seller was just happy to get them out of his warehouse.

The old shirts smelled terrible. But they didn’t have enough money to launder them. So they used their home washing machine one load at a time.

They didn’t have the money to rent a store, so they first started selling their shirts from a flea market. When that did ok, they found a store to rent for $250 a month – dirt cheap even in 1980’s prices. Why was it so cheap? Again, it was garbage no one wanted. The store had to stay unlocked at night so that students of the martial arts school upstairs had an entrance open for evening classes. No legitimate retailer would rent a store they couldn’t lock.

They wanted to create a catalog. But they couldn’t afford the glossy, thick, bound ones their competition had. So, Mel wrote his own. They couldn’t afford photos. So, Patricia drew pictures of their clothes. They stapled, addressed, and mailed them all themselves.

They couldn’t even afford shelves for their store, so they used wooden fruit crates Mel found in the garbage outside a market.

On and on, Mel and Patricia made do with what they had on hand, often, literally, garbage.

When Patricia and Mel were deciding on a name for their company, they thought about the surplus clothing they were buying. Most of it from unstable tropical countries. Aha. The perfect name of their business would be: Banana Republic.

Patricia and Mel Ziegler founded Banana Republic which they sold to The Gap in 1983, and continued to run for 5 years after the acquisition. During Patricia and Mel’s tenure, Banana Republic became one of the most successful apparel retailers in the world, with more revenue per square foot of retail space than any other retailer in the United States – double the national average.

Of course they had more resources and capital than they knew what to do with after the Gap acquisition, but the only way they got there, the only way they got to that point and out-competed everyone else, was doing the same thing Billy Beane’s been doing. They went with what they had on hand or could find in the trash. They refused to reach for things they couldn’t acquire. They didn’t sit around wishing the universe would change to meet their dreams.

As you can read in the wonderful story Patricia and Mel Zielgler wrote about their founding of Banana Republic in Wild Company, Mel and Patricia probably lucked out finding those jobs at that newspaper prior to Banana Republic. That’s afterall where they learned journalism’s classic proverb: “Go with what you’ve got.”

P.S. You should follow me on Twitter: here for more articles.

Here are a few of the websites and commissioned challenges that helped these Basecampers score their job here. Note: our company was called 37signals before we became Basecamp in 2014.

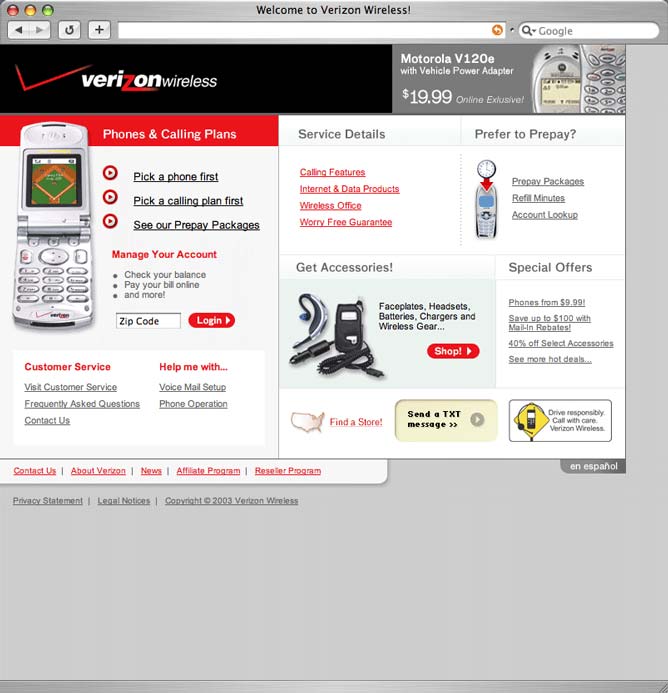

Ryan Singer (Designer, Product Manager) was one of a few designer candidates that Jason picked in 2003 for a chance to join 37signals to work on client projects. The design challenge? Redesign the Verizon Wireless homepage. Ryan showed a great sense of clarity despite little to no direction, and he’s been at Basecamp ever since.

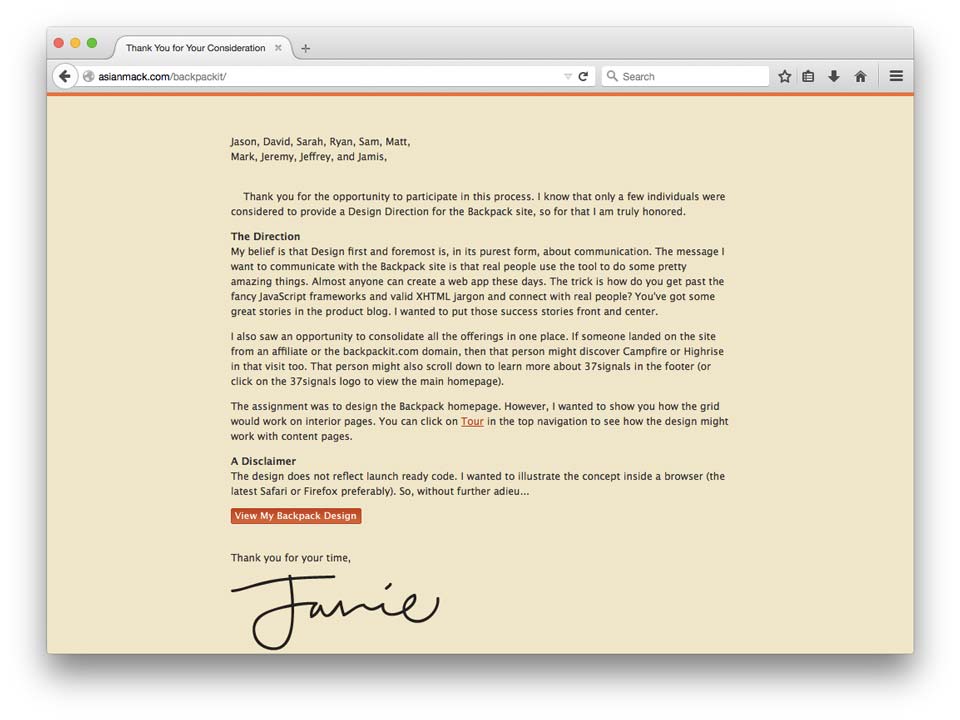

Jamie Dihiansan (Designer) met Jason early on in his career. 37signals wanted Jamie to apply for a new design position, but he wasn’t ready for it. Years later, timing finally worked out and Jamie applied for a new design position with a carefully crafted letter and a Backpack redesign.

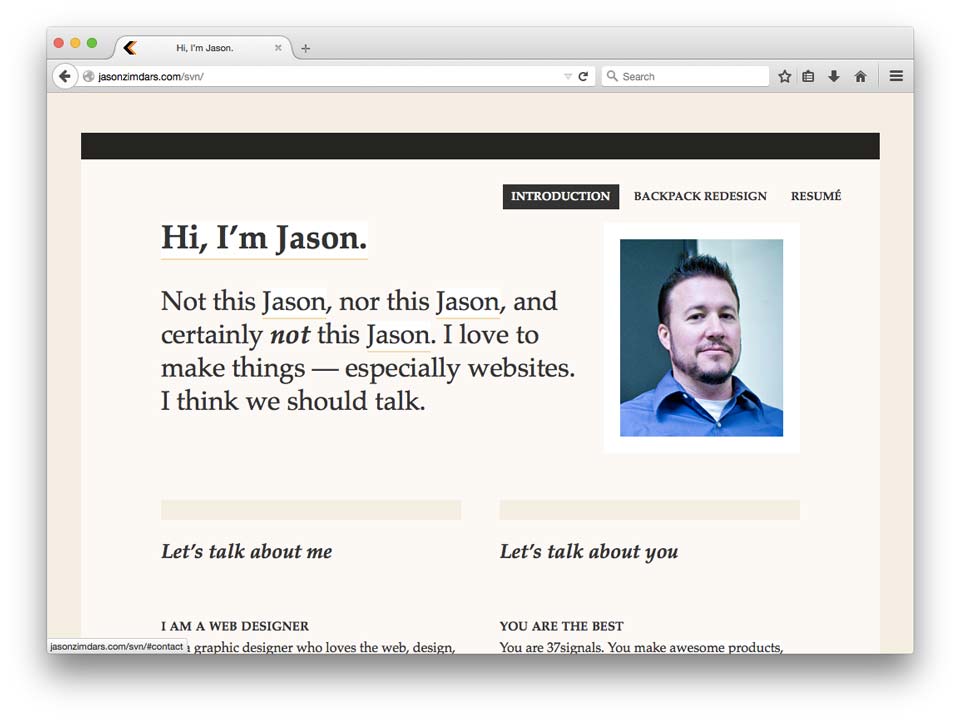

Jason Zimdars (Designer) was quick to respond to this job posting. Turns out, JZ didn’t get the job, Jamie (above) did. Despite that, JZ still had great work and kept in touch. When 37signals had room for a new designer role, we asked him to apply and he came back with the new gold standard in applying to a job.

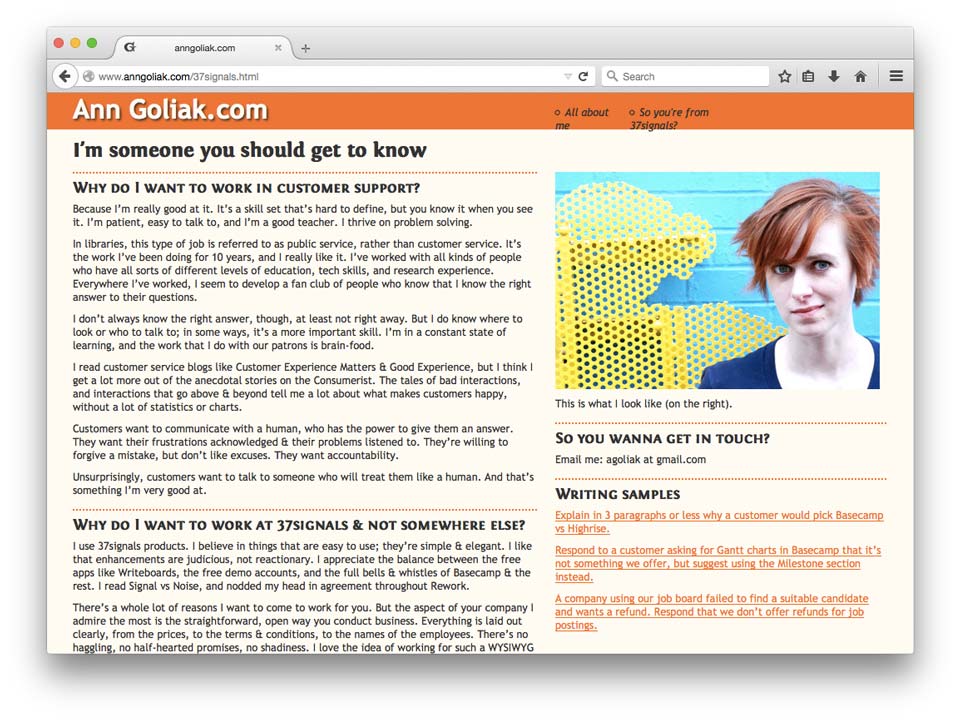

Ann Goliak (Support, QA) was a librarian when she first came across a Support position on our blog. Two hours later, she shot us an email and quickly forgot about it—she didn’t think she’d hear back. A month later, she heard back from us and whipped up a meaty page on why she’s a great fit.

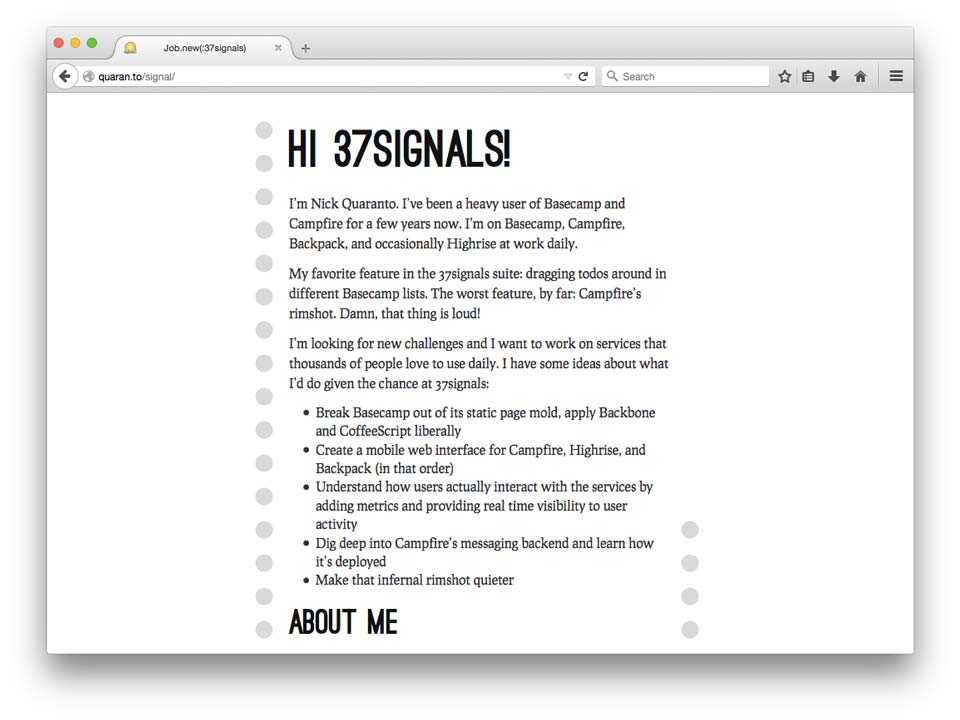

Nick Quaranto (Programmer) wanted to move back home. Working remotely seemed like the best way to do that. Nick applied to 37signals out of the blue, thinking it was a longshot. But a descriptive site showcasing his passion convinced us otherwise.

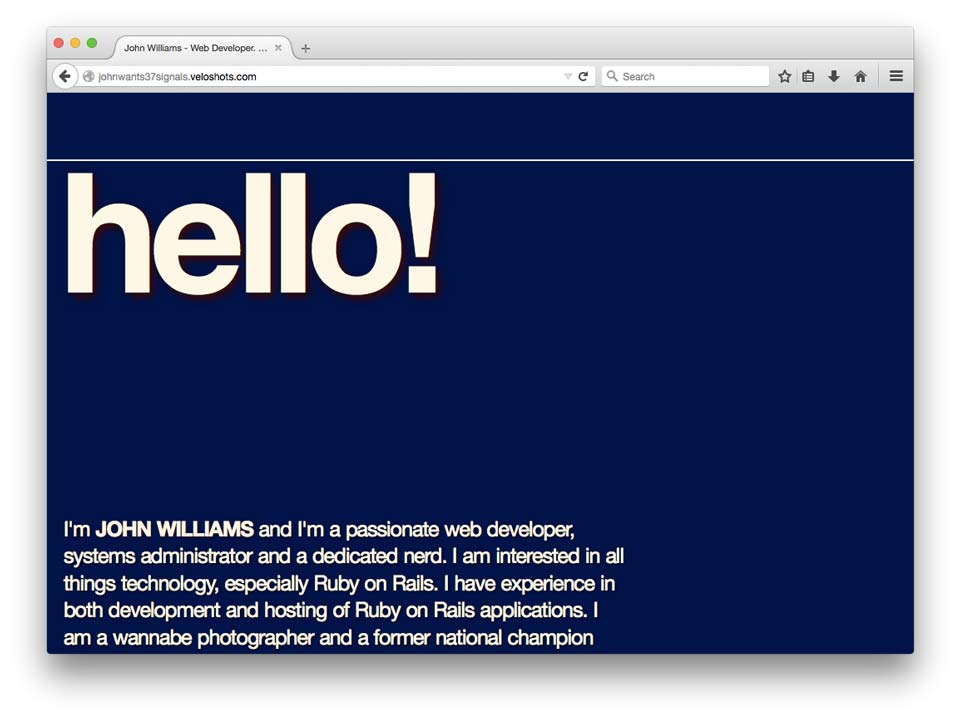

John Williams (Ops) was tipped by his brother that there was an ops opening on the 37signals Job Board. John rose to the top with a personal site that gave him an extra edge over all of the other candidates.

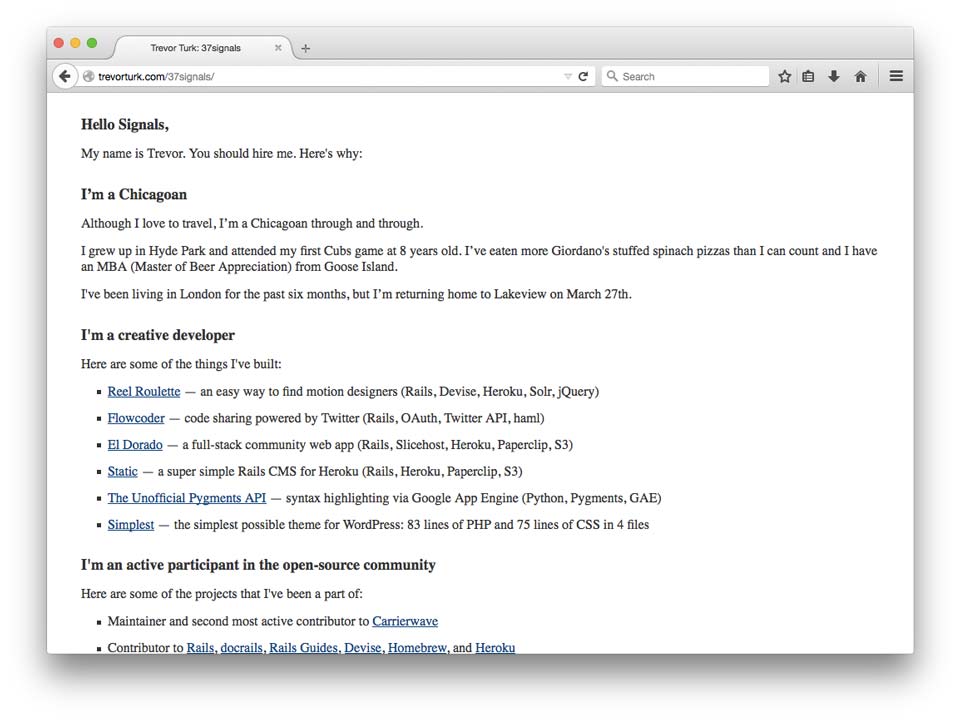

Trevor Turk (Programmer) was working as a contractor during a short stint in London when he came across a programmer job posting on our blog. He worked up a straight-to-the-point page to toss his hat in the ring. Turns out, it was everything he needed to do to join the team.

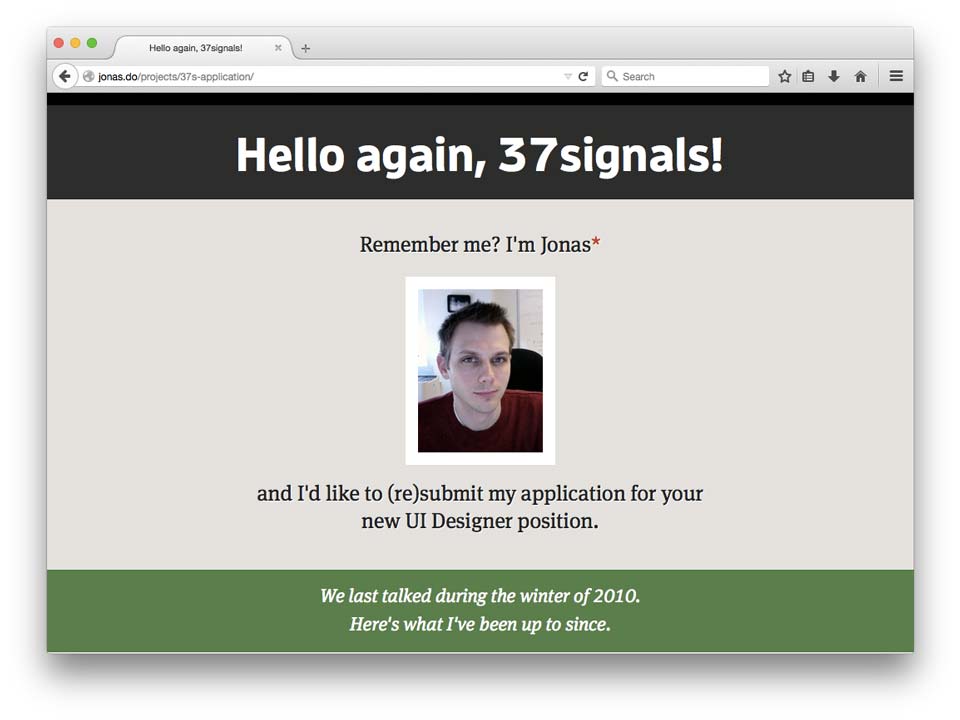

Jonas Downey (Designer) reached out to Jason after he tweeted about a new design role within 37signals. Jonas interviewed, but ultimately didn’t get the job. A half-year later, another design role opened up. Jonas applied again, knocked his design challenge out of the park, and he’s been a happy Basecamper since.

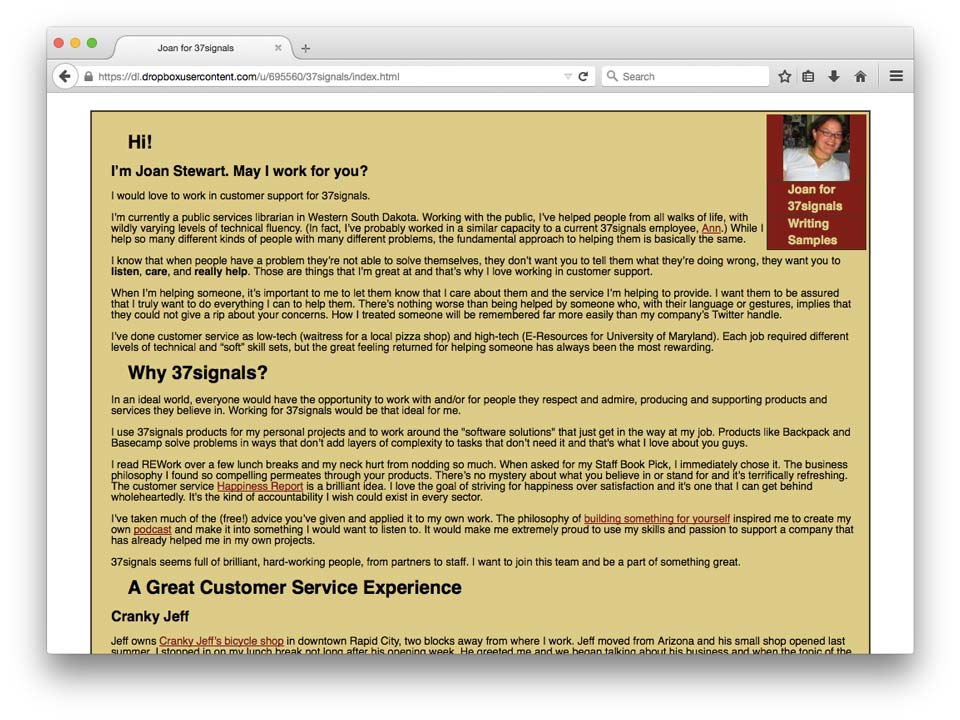

Joan Stewart (Support) was a librarian, a Backpack user, and a regular Signal v. Noise reader. Knowing that Ann was a librarian, Joan thought “if she could work at 37signals, so could I.” She took the time to whip up her own page, and now Joan is a happy Basecamper, too.

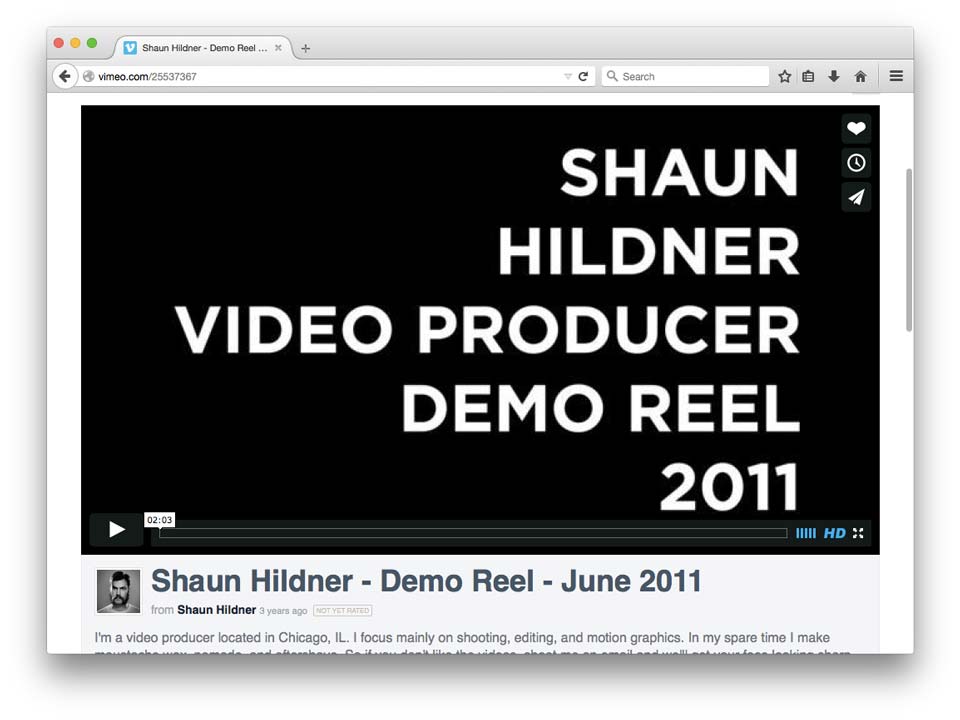

Shaun Hildner (Video Producer) was quick to shoot an email to Jason after seeing him tweet that 37signals was looking for a video producer. His reel got him an interview, and his test got him the job.

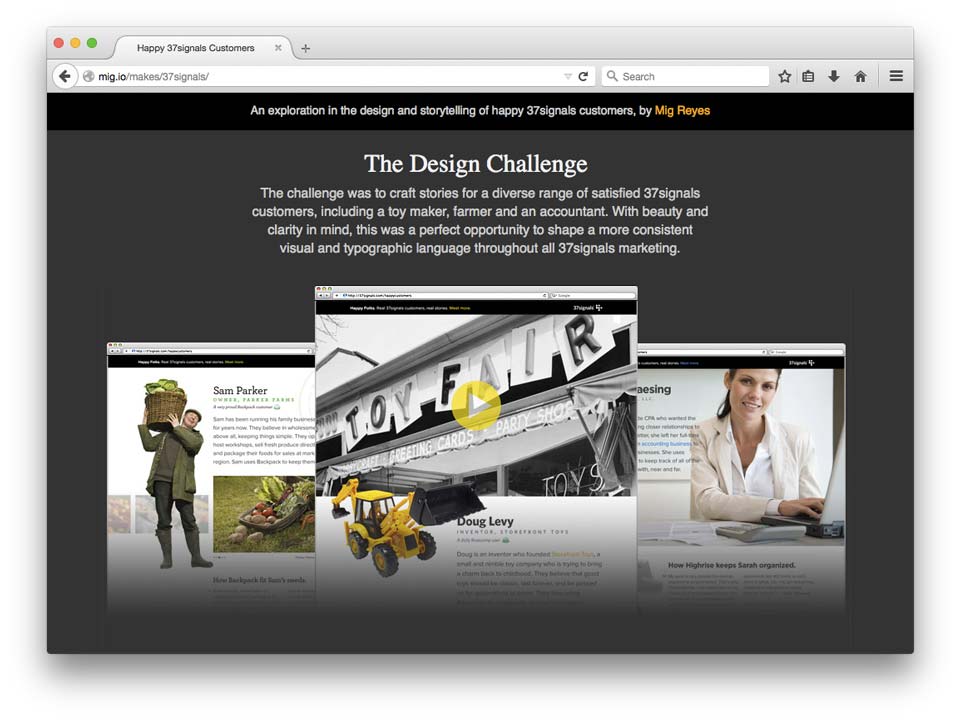

Mig Reyes—that’s me!—(Designer) dropped an email to Jason looking for a written recommendation when he was applying for a totally different job in Chicago. Jason offered, “would you be up for working with us at 37signals instead?” A few meetings with the team in Chicago and a design test to boot, Mig became the next Basecamper.

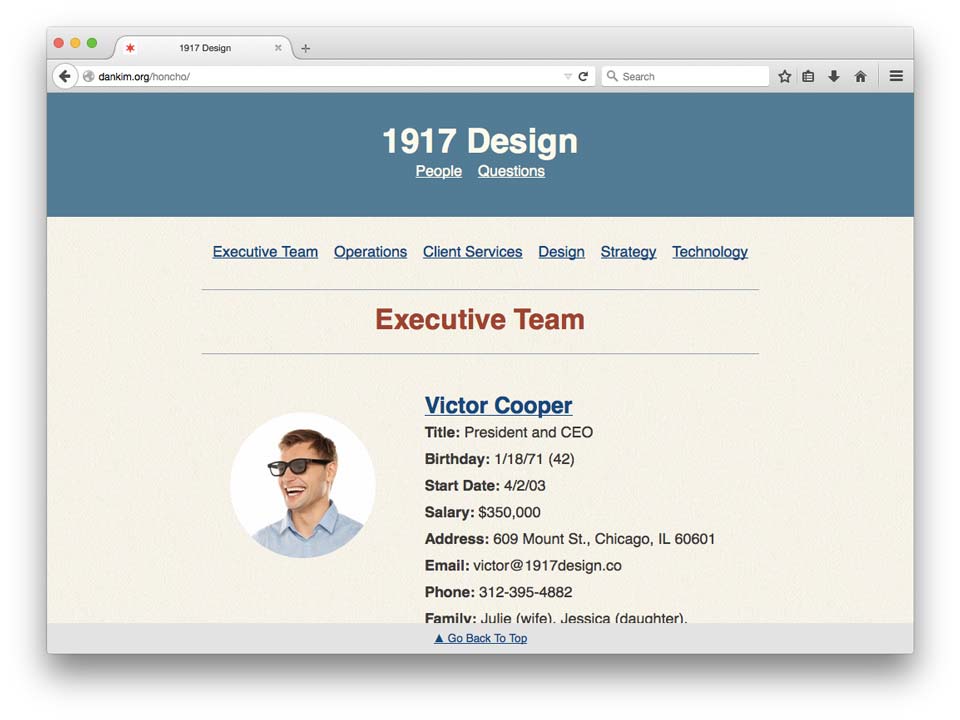

Dan Kim (Programmer) was just about finished taking an advanced HTML and CSS class at The Starter League. He emailed Jason if there were any opportunities, but there weren’t at the time. When we started to work on Know Your Company, Jason reached out. Then after a couple of lunches and a test project, Dan became a Basecamper.

Jim Mackenzie (Support, Programmer) noticed he hadn’t seen recent Signal v. Noise posts after updating his RSS reader. Out of curiosity, he visited our blog in his browser and stumbled upon this job post and sent us a strong pitch and some work on why we should hire a stranger from the UK.

Conor Muirhead (Designer) had a coworker mention that Basecamp was hiring a product designer. Considering a job switch himself, Conor pulled the trigger on firing off this email to Jason. Conor’s effort put him into consideration for the job, and he followed it all the way through with his fully thought out design challenge.

James Glazebrook (Support) was tipped by Natalie, already one of Basecamp’s very own Support team members, that we were hiring someone to cover European hours. James had read REWORK before, so he knew we valued applicants going above and beyond. The result? 37 reasons why we should hire him.

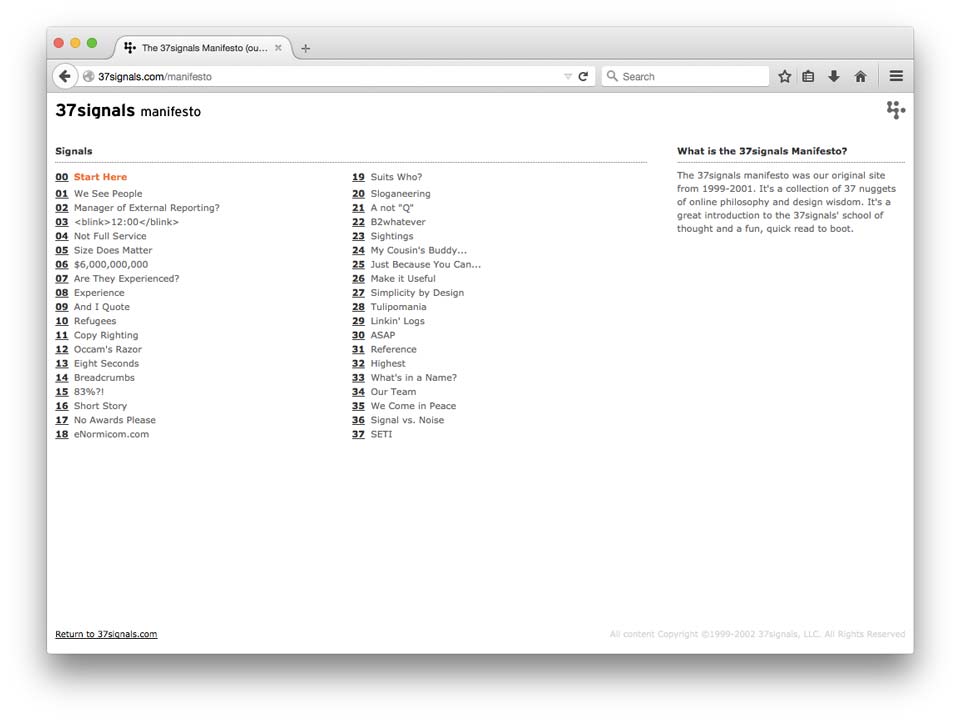

And of course, the original 37signals Manifesto that helped land us plenty of our former clients when we were a web consulting agency.

By the way, we’re hiring a programmer to lead Android and a designer to do brand and marketing. If you’d like to join the team, reach out to us!

Some people are destined for mediocrity.

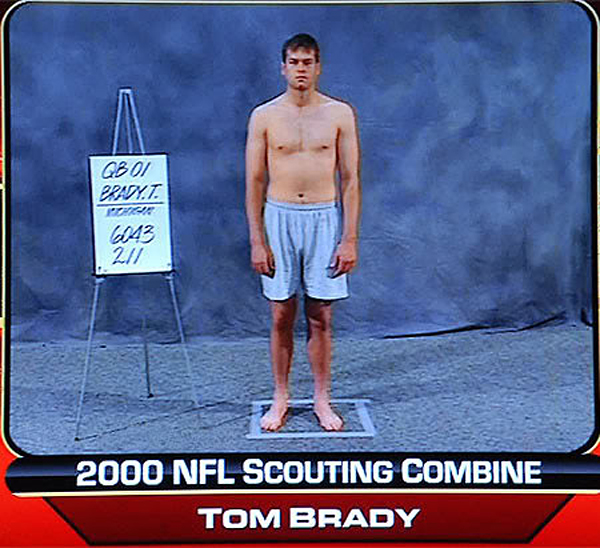

Take this guy for example: A college kid, who, despite a semi-decent college showing as an American football quarterback, was drafted 199th by a professional team. You don’t have to be a football or sports fan to realize how terrible that is.

And he wasn’t drafted for anything near a starting position. He was drafted as a fourth-string quarterback. You’ll hardly find any active fourth-string quarterbacks. In the rare occasion the third-string gets hurt during a game, you’ll sometimes see a random player, like a wide receiver who played quarterback in high school, come in. That tells you how valuable a fourth-string quarterback is: about the same as a high school kid who doesn’t even play the position anymore. Fourth-string quarterbacks are often just practice squad dummies – fresh meat for the real players to pound on, maybe they get a few throws in during the last seconds of a pre-season game.

And sure enough, our bottom-rung quarterback, during his rookie season, got to pass 3 times. 1 completion. For a total of 6 yards.

But then things turned around. He moved up to second-string the following season, and the starting quarterback was injured, which gave him a chance to start.

That season, this mediocre quarterback, Tom Brady, won the Super Bowl for the New England Patriots. And not just a win, but he was their MVP. He went on to win the Super Bowl again 2 years later. In his career, he’s made the playoffs a dozen times, been to the Super Bowl five, and won three of them. He might even be on the way again this year.

Tom Brady is one of the best quarterbacks of all time. And everyone almost missed him.

A combine is an intimidating looking machine for harvesting grain. The name is derived from what it does: combines the steps for harvesting – reaping, threshing, and winnowing. Those things are also often metaphors for how we do hiring. Reap the best candidates. Harvest the top prospects. Winnow the resumes.

Professional league sports teams have no shortage of young athletes who want to play for them, so they’ve created their own combines.

For example, the NFL invites about 300 college kids in February for a weeklong trial. They are put through the things you probably assume they are put through: running, jumping, lifting heavy things. They even go through interviews, intelligence tests, and have half-naked photos taken of them for later scrutiny.

That’s why Tom Brady was picked 199th as a fourth stringer. He was terrible at the combine. The 40 yard dash is one of the combine’s tests. Tom Brady ran it in 5.28 seconds – the worst score in the history of the combine. And those photos they take? Here’s Tom in 2000:

Doesn’t scream world class athlete. But fortune would lead to Tom getting a starting job where he could show off his true performance.

Here’s the funny thing, though, Tom Brady isn’t the exception at the combine, he’s the rule. In 2008, Dr. Frank Kuzmits and Dr. Arthur J. Adams from the College of Business at the University of Louisville began publishing their research of the NFL combine. Those physical tests don’t actually predict how athletes perform. Bottom scoring combine players find themselves at the top of the professional world all the time. And top scoring combine players, contain a ton of washouts – top draft picks who you’ve never even heard of because they lasted just a single season.

And it’s not just the physical tests that don’t work. The intelligence tests fail too. Kuzmits and Adams also studied the Wonderlic, which is a rudimentary test of intelligence given to all NFL quarterbacks. NFL quarterbacks have a lot to process. They need to be sharp.

Except, again, no correlation was found for the scores on those tests and the performance of quarterbacks in the NFL. Dan Marino has one of the lowest Wonderlic scores of all time, but Dan Marino is also one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time.

Hockey and basketball scouts have the same problem.

These combines don’t work.

But this isn’t just a problem for professional sports. There’s plenty of other studies showing how tests we’ve created to find top candidates in fields like academic recruiting and finding good teachers fail at predicting anything.

The only way we can judge someone is by observing their actual performance.

Highrise is the small business CRM tool that recently spun out from Basecamp. One catch: As the new CEO of Highrise, I needed to find a brand new team. No one from Basecamp was coming over in the move.

I reached out to some folks I knew, dropped hints we were looking for people in blog posts and Tweets, and the process began. But instead of relying on tests, and multiple rounds of grueling interviews over weeks and months, I just followed my gut and kept what I was looking for simple (inspired by Joel Spolsky):

And after about the first 10 minutes of a phone call, I had a pretty good idea if you fit. But I didn’t belabor the decision. I know I don’t have a test that could accurately predict whether you were any of these things. So I didn’t spend time trying. We immediately went into short term contracts to observe real performance. And away we went.

We saw if we worked well together and if we got a bunch of stuff done. And we did. A lot, very quickly. And with that real world evidence, I had the data I needed to bring together the official new team behind Highrise!

Please, let me introduce you to:

You’ll hear from Chris if you need help with Highrise. He’s head of our customer support. Chris got my attention when out of nowhere he started doing customer support for a software project of mine when I hadn’t even hired him to do so. Then he sent me a job application, when I wasn’t even looking yet, using my very own software to create the application. Chris knows how to communicate and how to help. He’s been an incredible asset to Highrise.

Michael is the new CTO of Highrise. I met Michael in 2011 when we were in Y Combinator together. He was the engineer behind creating an awesome photo application called Snapjoy. Great guy and wickedly smart. We hit it off immediately. Snapjoy was quickly acquired by Dropbox, and you’ll see his handiwork all over what Dropbox has done with Carousel and photo storage.

Wren is our lead designer. After a small test project for one week, I knew I wanted to work with her full time. She’s quickly improved and refreshed many areas of Highrise, including a beautiful redesign of the homepage. You should catch one of the talks she’s giving at a design conference soon.

Zack is the first software engineer and resource I brought in to help me at Highrise. We had a ton to learn and juggle instantaneously, but if you’ve noticed the extremely fast pace of improvement we were able to make as soon as we started, it was because I had Zack.

I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have found such a talented group of people. But it was also because I didn’t rely on a combine of tests and artificial situations to judge these folks. We got nice, insightful people together to work on actual problems. Our performance in the real world did the rest.

Stay tuned, we’ll be using SvN to share a lot more of the interesting things we discover while we build Highrise. Please feel free to say Hi to all of us on Twitter too; we’d love to meet you. And if you want to follow the fast pace of things we’re getting done at Highrise, you should check out our product updates: here.

Almost ten years to the day, we launched a free service called Ta-da List: A simple way to manage and share to-do lists online. It’s funny to read the announcement now. You need a MINIMUM of Internet Explorer 6 to run it! Ha.

Well, we retired Ta-da List in May, 2012, as it had run its course, and we weren’t looking to update it to keep pace with progress. But what we didn’t do, was to kick off everyone who was happy to use what they had. Ta-da List is part of our legacy, and the courteous thing to do is to respect your legacy.

If you have a Leica M3 – a camera produced between 1954 and 1967 – they’ll still fix it for you in Germany. Half a century after they stopped selling it! That’s legacy, and an inspiration.

In 2014, there were just under 5,000 people still happily using Ta-da List to track their todos. That makes me smile. No, it’s not the best to-do tracker in the world. There’s no mobile app. It’s antique software. But it’s our legacy, and it feels good to be there and be dependable for the users who are happy with what they got.

When we Became Basecamp that was a theme we talked about a lot. The internal phrase is that we want to produce software that’s around #UntilTheEndOfTheInternet. So much software and so many services these days are unreasonably flaky and undependable. Not in the sense that they crash (well, that too), but that they simply disappear from one day to the next because of whimsy, acquisition, or worse.

I don’t want to be a digital landlord that evicts people who placed their trust and their data with us, just because “our priorities have changed”. At the same time, we also don’t want to continue selling or offering antiques to new customers. This is the compromise: No new users, but the ones we got we’ll take care of forever.

So cheers to Ta-da List and the 5,000 people still using it. We’re glad you’re still here, reminding us of who we are and where we came from.

By 1933, at 22, a Taiwanese-born entrepreneur had built a successful clothing business importing socks from Japan. Six years later, he moved to Japan, and his company was booming. During World War 2, he expanded his business empire to include selling slide projectors to the Japanese government for all the training they were doing during the war. And he kept expanding into other products – like charcoal mining and air-raid shelters.

The war was good to him, financially, for a time. Eventually, he found an accounting problem with one of his companies. The government was giving him raw material to manufacture engine parts, but inventory was missing – probably being sold by an employee on the black market.

He went to the Japanese military police to get help investigating. But they arrested him, and put him in a military prison where he was starved and tortured. Released 45 days later, the torture and starvation had taken its toll. When he finally recuperated, Japan had lost the war. The economy was in shambles. His factories and businesses were destroyed. He had little left.

But he started again. This time buying real estate people were now selling off at huge discounts. In just a few years, he was sitting on a million dollar real estate empire. His experience with starvation and inadequate food in prison inspired him to start a food business. He began paying young kids to collect sea water, which he’d evaporate, then sell the remaining salt.

But then, the occupying American force arrested him for tax evasion on the $50 a month he was paying the young kids – an amount he claimed was meant for their college scholarship (a non-taxable expense). He countersued, but the lawsuit dragged out, leaving him stuck in prison again, this time for years.

He was eventually released with a clean record, all charges dropped. But the government had already confiscated and sold off everything he owned – all the real estate, the salt company, the charcoal mine, his home. He was flat broke.

So he started again. He helped start a new bank, which got off to a good start. Except the company executed a number of bad loans. And the bank was forced to file bankruptcy. Depositors went after what little he had begun to accumulate.

So he started again. He still had a strong urge to create a food company. He turned his tool shed into a makeshift laboratory, and worked for a year trying to invent a new food product. Experiment after experiment failed.

But in 1958, at the age of 48, this entrepreneur finally hit on an idea that eventually became a company worth 700 billion dollars on the Tokyo stock exchange.

Momofuku Ando invented instant ramen noodles. Ando’s story is an inspiring tale of perseverance. And yet, I know most people reading this discount the tale: Ando possesses a willpower most of us will never have. We might be a little inspired by Ando, but we can’t possibly imitate his perseverance.

But, I don’t think that’s true. Ando’s story goes much deeper than that.

Why do kids drop out of college? A lot of reasons. Academic, monetary, even legal. It turns out though, there’s something much more fundamental.

Vincent Tinto is a professor at Syracuse University. He’s well known for his theories on students’ persistence through higher education. His research produced what’s known as the “Model of Institutional Departure”. He’s figured out why kids don’t succeed in college and dropout.

Tinto’s model informs us that, above all else, college is a transition from one community to another. Our success at college depends on how well we integrate ourselves into that new community.

What happens if we go home every weekend, to visit high school friends and sweethearts, instead of making friends in our new community? We don’t integrate. We don’t get help from new friends going through the same thing or academic advice from new mentors. Instead, we tend to drop out.

Tinto’s model has proven incredibly useful in improving how we educate, not just undergraduates, but even remote learning programs, and classes for adults continuing their education. And it extends far past education in describing how people persist.

The model wasn’t even unique. It was in large part derived from a model about suicide created by Emil Durkheim in 1897, who found that suicide rates were dependent on the group and society people found themselves in: if people fully integrated into their groups and communities, suicide rates decreased.

If people weren’t alone, they persevered.

While Momofuku Ando was in military prison camp the first time, a fellow prisoner, who Ando befriended, was released. Ando asked him to contact another friend – a lieutenant in the Japanese Army – who eventually arranged for Ando’s release. If it wasn’t for those two friends, Ando would have likely died in prison.

Then he started his real-estate empire. But that wasn’t even his idea. Another friend, Fusanosuke Kuhara, an entrepreneur who helped create what would become the company Hitachi, mentored Ando. His advice when Japan’s economy was ruined after the war? “Buy all the cheap real-estate.”

And when all of that fell apart, and Ando found himself completely broke but still able to start a bank, it was because he still knew enough people who gave him deposits to begin that bank.

And with instant ramen, he is indebted to the understanding of his wife who let him continue to work and chase his dream. It was her idea to create a laboratory out of their tool shed. And it was studying her cooking that actually gave him the idea how to create instant ramen.

Ando’s persistence didn’t come from suffering all by himself. It came from the people he surrounded himself with.

As I look back on the things I’ve accomplished in my life, I can point to obstacles and paths where I might have given up or not started at all. Then, I see the people who gave me a little nudge or lift to get to a better place.

When I wanted to start my first company Inkling in 2005, I applied to Y Combinator, an early stage investment program. Trouble was: the person I was originally going to apply with backed out at the last minute. And Y Combinator often requires its companies to have more than one co-founder.

This would have been an easy place to have just given up. But I had a lot of loose ties to other people who I started reaching out to. I thought of a friend, Adam Siegel, who I hadn’t spoken with in awhile, but who had mentioned a year previously over lunch that he was looking to create a new business. He might be game. And one lunch later, he was on board with my new business idea. We applied to Y Combinator together, got in, and away we went.

Years later I was trying to figure out my next project. I remember a lunch with another friend, Andrew Wicklander. We get lunch every 12 months or so. After a chat about how much we missed Basecamp’s Writeboard, I had the motivation to commit to something that became a pretty successful software project called Draft. And only successful because a lot of other loose connections and friends helped me spread the word.

With Draft, I had emailed a friend I’d stay in touch with every so often: Would he help mentor me a bit with Draft? And he did. And all that turned into him, Jason Fried, asking me to take over a software project he had started – Highrise.

I’ve gotten a lot of help from friends and loose connections I’ve cultivated over the years. And what I’ve found is that it doesn’t take becoming some schmoozing, glad handing, awkward-networking-event-attending extraordinaire. I’m one of the most introverted people I know. If there’s a conference, I’m in the back row so I can be the first to leave. If there’s a party, I’m probably not at it, or was there early and left before you even showed up.

But it isn’t hard to track the people you meet in something like Highrise or a notebook or even index cards. And keep those loose connections alive with an occasional email, coffee or lunch. Just think of all the people you haven’t heard from in a month. What’s stopping you from a just sending a quick: “How’s it going?”

And finally, don’t be afraid to be honest with all those connections and actually ask for help. Too many of us, especially those running businesses, suffer in isolation. While we create and run businesses, we tend to hide the pre-success from friends and people who could help. Why? Because pre-success can feel a lot like failure. It’s often not fun finding and keeping those first customers.

We’re told to fake it till we make it. Nonsense. I can’t believe how many people tell me how well their company is doing, and three months later it’s out of business. If only they had shared their challenges, maybe I or someone in their network could have helped.

On January 5, 2007, Momofuku Ando died from heart failure at the age of 96. Again, we have a chance to see how good Ando was with surrounding himself with people.

6500 people attended his funeral. It was held at a baseball stadium. It was invite only.

It all started with an Ewok.

That’s my two-year-old daughter on Halloween. To complete the effect, I decided to dress up like Princess Leia in Return of the Jedi (her jaunty Endor speeder outfit, not the metal bikini) and went on the hunt for a sweater that would resemble her camouflage poncho but be something I’d wear again. Browsing the Nordstrom website, I discovered the Bobeau Asymmetrical Fleece Wrap Cardigan in “Heather Pinewood” and remembered I had seen it recommended on a fashion blog I follow. I ordered the sweater; it fit great and at least two people recognized me as Leia. A success!

Then something happened. I started wearing this sweater almost every day. It was the perfect layering piece for my work-at-home wardrobe while also looking refined enough to wear for errands around town, and I didn’t want to take it off.

Before long, I began noticing this sweater everywhere in my orbit. I ran into a friend at my local coffee shop and she was wearing it. I tweeted about my love for the cardigan and heard back from friends saying they had it too. I wore it over my workout clothes to my exercise studio and an instructor said not only has she seen other clients sporting it, but that she owns it in gray and brought it to a weekend getaway — only to find her friend wearing it, too, in a dusty pink. My husband spotted a woman in the cardigan at our local public library. I ordered the sweater in a second color for myself and bought two more to give to family members as Christmas presents.

As of this writing, the Bobeau Asymmetrical Fleece Wrap Cardigan has 4.5 stars from 2,385 reviews on Nordstrom’s website. Apparently I’m not the only satisfied customer, especially when you consider that the other items in the “People Who Purchased This Also Purchased” section only have a few hundred reviews. And when I sorted women’s sweaters to look at just “Featured” products, I found that most of the items on that page have zero reviews. Somehow the Bobeau Asymmetrical Fleece Wrap Cardigan, which is essentially a fancy Slanket with an awkward name, had gotten incredibly popular. And I wanted to know why.

Nordstrom’s public relations department was unsurprisingly loath to disclose details about the sweater, like how its sales compare with other women’s apparel items or whether it did any special marketing for the cardigan. Trend Request, the Los Angeles-based company that owns the Bobeau brand, was similarly reticent, although it did credit Nordstrom for popularizing the “one button,” as it referred to the cardigan. (The sweater is also sold at Dillard’s, but only in three colors online, compared with 30 plus on Nordstrom, and has no reviews on the Dillard website.)

“We can’t share specific numbers about what makes this a best-seller, but we can say that it’s very popular with customers, especially during the holiday season,” wrote a Nordstrom spokeswoman, whose colleague had told me earlier that she owns two of the sweaters herself and put another three on her wish list.

I wondered if Nordstrom had heavily promoted the Bobeau sweater among fashion bloggers, who in recent years have proved remarkably powerful in driving sales toward retailers. After all, I’d first heard about the cardigan on Extra Petite, a blog that has published Nordstrom-sponsored posts and uses affiliate links. But Jean, the writer behind Extra Petite, mentions on her site that she learned of the sweater from her friend Kat at Feather Factor, another lifestyle and fashion blog. And Kat, when I asked her about the cardigan, said she found it “randomly at Nordstrom one day wandering around,” then alerted her readers when it went on sale.

It turns out my other Bobeau-owning friends also came across the cardigan by seeing friends and co-workers wear it, or by browsing at Nordstrom like Kat. Not only that, but they were all as oddly enchanted with the sweater as I was. One friend, who owns it in four colors, wrote me five emails in rapid succession because she kept remembering more things she wanted to say, like how she also bought a black Bobeau maxi skirt because she was so impressed with the brand. Another friend, the one from the coffee shop, said she was “excited with glee” to get my email and needed time to compose her response so she could tell me her “exact feelings and love for this piece of clothing.”

There is something about this sweater that inspires women not just to buy it, but to practically stockpile it, recommend it to friends and talk about it with an almost religious fervor. What’s interesting about the Bobeau one-button is that it’s neither an example of a generalized trend like peplums nor an example of a luxury fashion item achieving “It” status like Valentino Rockstud shoes. This is a sweater that currently retails for about 40 bucks. I think about how wishy washy I am about purchases, constantly filling up virtual carts and abandoning them, and marvel at how easily this cardigan tips shoppers from “Hmm, that’s nice” to “I’ll take four and tell my mom about it.”

“So — I bought the grey version, wore it to work, and got tons of compliments,” wrote the sister of my coffee shop friend. “I immediately told my two office mates to order one each….They in turn ordered theirs, and then turned around and ordered more, after realizing the awesomeness of the Bobeau. I was also convinced to order another one, in pink….Our office laughter from Bobeau Fridays spilled out to the (small) department of women, and it caught on. After tallying it up, I think we had 12 other women order one each, some ordering two.”

Any business that aspires to make money from a product or a service — including, say, makers of project management software — dreams about this kind of natural and positive word of mouth. And as a consumer, I have no problem with this either. I seek out opinions from friends, and in turn I routinely recommend all sorts of stuff to friends, whether it’s a restaurant or a lip gloss or a thought-provoking magazine article.

And yet my devotion to the Bobeau one-button made me feel weird. With the advent of social media and targeted advertising, I’ve learned to be suspicious of word of mouth. Is it a genuinely organic process, or is it just shrewd brand management in an exceptionally cunning disguise? These days, brands want to be our friends. Brands want so desperately to be approachable and human that you get sanctimonious tweets from companies commemorating September 11 and equally sanctimonious tweets from other companies announcing that they won’t be tweeting on September 11. People throw around terms like “brand evangelist” and they are being perfectly earnest and we go along with it.

I worry sometimes that my tastes and preferences aren’t as considered as I’d like to believe. Why did I buy a Sophie the Giraffe teething toy for my daughter? Why did I binge watch True Detective? Why have I turned into a brand evangelist for the Bobeau Asymmetrical Fleece Wrap Cardigan? It’s vaguely depressing to think it was because I was in the thrall of a brand.

None of my other Bobeau-wearing friends seem to be having this consumerist crisis over whether Nordstrom subliminally — or overtly — influenced them to buy the sweater. They just really like the one-button for all sorts of reasons, many of which are echoed in the online reviews. It’s machine washable and comes in more than 30 colors. It has a pert little button. It’s cozy but not frumpy, ideal for wearing on plane rides or keeping at the office. Its drape flatters a variety of body shapes and it comes in Petite and Plus sizes. “Makes you realize how many articles of clothing DON’T fit that bill!” one friend wrote.

My coffee shop friend, who bought her first Bobeau while pregnant and now has two sweaters and two small children, said: “I feel like pregnancy and motherhood make you give up so much when it comes to fashion choices….Everything you own ends up getting stained or ruined so you can’t have anything really expensive or hard to take care of. But this is one amazing item that allows you to keep your fashion style without having to give up any of the other practical considerations.”

Maybe Bobeau and Nordstrom pulled off that rare feat of making and marketing a product that has mass appeal, and I should acknowledge that instead of acting like I was in a brand-induced fugue state when I bought my sweaters. It does feel oddly freeing, I’ve realized, to like something that thousands of other women of different sizes and shapes and lifestyles have also embraced. In an era of ever-increasing online tracking and data collection, it’s liberating to wrap myself in something whose ubiquity provides a kind of anonymity. The sweater is my invisibility cloak; marketers can’t discern anything unique about me because everyone has it. I could be a bosomy frequent flier or a lean Pilates instructor or that lady in your office who’s always cold. Or maybe I’m just a mom who started with a Princess Leia costume and ended up with a closet full of sweaters.

In 1949, Earl Bakken and his brother-in-law Palmer Hermundslie started a medical device repair shop in Palmer's garage. It was a terrible place to work – freezing in the winter, stifling in the summer.

We used a garden hose to spray water on the roof in a not especially successful attempt to cool the place down a few degrees. At least once during those early days, the garage was infested with flying ants.

Unlike your typical "successful" startup garage stories, they were in that garage for the next 12 years. In their first month of operation, they earned a whopping $8 of revenue. Even in 1949 money, that wasn't good. And, for the next several years, they just kept losing money.

In 1957, a chance encounter with Walt Lillehei, a heart surgeon desperately looking for a way to keep his patients alive during blackouts, led Earl to invent the world's first battery operated pacemaker. Earl and Palmer's company, Medtronic, would become one of the leading biomedical companies of our time. They invented the pacemaker industry. And for the next 30 years, dominated the market.

But by 1986, their company had fallen from a 70% market share to 29%. Despite spending many millions on R&D, the company couldn't compete anymore. The company was stuck again.

Could someone save it?

Mars, similar to Earth, rotates around its own axis every 24 hours and 39 minutes. And when a solar-powered rover lands on Mars, most of its activity occurs during Martian daytime. So engineers on Earth studying Mars rover data, adopt the ~25 hour Martian cycle. Laura K. Barger, Ph.D., an instructor at the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School, wanted to know what kind of effect that has. Does 39 minutes really make that big of a difference?

What she found from her studies was that NASA engineers who could correctly sync their own wake/sleep schedules with the 25 hour day did fine. But they had to make a concerted effort to adapt using countermeasures – take the right naps, alter their caffeine intake, use light exposure, etc.

But those people who couldn't adapt, or didn't bother to try, suffered significant performance problems from fatigue. She also found that on the first Mars rover mission, The Sojourner, engineers were so exhausted after a month that they formed what NASA managers called a "rebellion" and refused to work on Martian time any longer.

We spend billions of dollars on space exploration and engineering, lives are at stake, and simply getting our circadian rhythm synced correctly with our tasks and with our team could make or break an entire operation.

It underscores the importance of what appears trivial: achieving the right rhythm.

In 1987, Mike Stevens was assigned to be vice president of Medtronic's product development. When he looked at what was happening at Medtronic, he noticed that there were actually quite a few good ideas in the pipeline. But when they were just about ready to launch, a competitor would spring up with a similar product. Medtronic would delay the launch, debate, discuss, and try to figure out a superior version to launch instead. The company was in a cycle that led to a decade of no new products.

Steven's solution was incredibly simple. He put the whole company on something he referred to as a "train schedule". He and his executives set dates far into the future for when new products would be invented and launched.

I chose that phrase "would be invented" carefully. Because these weren't product ideas they already had and now just needed development. They didn't even know yet what they would develop and launch – just that they would launch something, anything, on schedule.

The effect was tremendous. The company could still debate and plan, but employees knew decisions needed to be made by a certain date or else they'd miss the train.

Medtronic's market share climbed back steadily from Steven's promotion date, and in 1996, they were back above 50%.

Years ago, I was sick of not having a bigger audience around my writing and software products. My Twitter account was stuck at 200 followers. And I didn't know yet what to improve, how to differentiate myself, or how to market my products better. So, I committed to writing and publishing at least one blog post every 7 days. That's it.

The first post, crickets. The next post, more of the same. And the next and the next. Very few people read what I was writing. But the rhythm got me through the points where many would have given up. And to the points where I started getting better.

And years later, I had gotten so much better that hundreds and then thousands of people began reading my blog posts at Ninjas and Robots. The new audience helped me launch a product, Draft. But of course, I had a familiar feeling of being stuck with Draft, writing software amongst a sea of other writing software.

I had no idea how I was going to compete, what I was going to build, how I was going to market the thing. But I did the same thing I did with writing, I committed to a cycle of launching as many new features and improvements as I could every few weeks. That's it. But the momentum fortunately caused a lot of excitement.

@natekontny dude, how do you release such big features so fast? I've never seen anything like it from another startup. It's just you right?!

— Sean Everett (@SeanMEverett) May 16, 2013Some folks even compared it to Christmas :)

@gooddraft It feels like Christmas receiving an email with the latest news about Draftin.

— Amanda L. Goodman (@godaisies) September 17, 2013No matter what my revenue looked like, or how terrible my user growth might be, I knew I had to release something. The rhythm trumped everything and kept propelling me forward.

Back in February of 2014, 37signals announced they were renaming themselves Basecamp to focus on their project management software. They would look at selling off their other products, especially their second most popular product, Highrise, a small business CRM tool.

You can imagine what that kind of announcement did to customer growth of Highrise. Even worse, as soon as the announcement was made, more than a few competitors took the approach of putting up mini-sites that read: "Goodbye Highrise. Highrise is shuttering; here's how you migrate your data to us." Highrise wasn't going away, but that didn't stop them.

So when Basecamp decided to spin-off Highrise as a subsidiary, I faced quite a bit of negative momentum as Highrise's CEO. But this looks like a challenge previous versions of me has faced before on a smaller scale.

On day one, I established a train schedule – we'd make major announcements on a regular basis. If something isn't ready, it misses the train. But an announcement is going out; something better be on it.

I didn't start with a big team. It was just me and one more developer, Zack Gilbert, but we were going to ship whatever we could ship in one month, and make a big deal out of it.

It wasn't an announcement filled with very big ideas or changes. We only had 30 days to begin learning a large code base, and had plenty of other tasks and support requests to handle. But we had a schedule to keep.

And our first announcement went out. Then another one month after that. And then another. Now with a bigger team, and even more experience with the product and advice from our users, the announcements are getting more interesting.

The result? Highrise HQ LLC has only technically been in business a little over 3 months. But our rate of customer growth has increased by 39%! And we're seeing growth numbers that look a lot more like what the numbers were before Basecamp made their announcement.

It's far too soon to proclaim Mission Accomplished, we have many mountains to climb still and plenty of low points along the way I'm sure, but it's apparent what kind of effect a rhythm can have on creating a product, syncing a team, and communicating with customers. And things are starting to look a bit familiar :)

Loving the new features on @highrise this morning. Feels like an early Christmas present.

— Robert Walker (@robjwalker1) December 3, 2014The wonders of version-less software as a service are extolled from all corners of the internet: Nothing to install! Updates come to you automatically! Everything just gets better all the time. And that’s all true, but it’s not the whole truth.

The flip-side of this automatic wonder is that you’re forcing constant change on everyone. The only way to prevent that from being unbearably grating is to make it incremental, and exclusively additive.

There’s no room to change your mind about the fundamentals once a sizable customer base has been trained to expect the familiar. Anyone who’s ever tried to remove a feature from internet software will likely be so scarred from the experience that they never attempt it again.

This is where it’s so easy to cry boohoo as a developer: “Oh, those damn users just can’t see or accept the brilliance of newness! If only they would be patient, relearn everything for me and my creations, we’d all be better off!”

The fact is they probably wouldn’t. Most software just isn’t important enough to warrant a steady stream of newness friction. Makers eat and sleep their software all day long, so most changes seem small and inconsequential. But users have other worries and changes to face in their daily lives; learning your latest remix is often not a welcome one. They invested attention to learn the damn thing once, then went on with their merry life. And what’s so wrong with that?

Nothing, I say. We have a very large group of customers who still enjoy Basecamp Classic. It’s been 2.5 years since we released the new version, but the Classic version continues to do the job for them. It just hasn’t been a convenient time for those customers to disrupt their work to upgrade Basecamp, or maybe they just don’t like change. It really doesn’t matter.

That doesn’t mean they’re not happy customers. Just the other day one wrote to say how much they loved Basecamp, yet felt obliged to apologize for not yet upgrading to the latest version. There’s nothing to feel bad about! Except that the software business makes us feel like there is.

Installed software didn’t have this kind of tension because of versions. If you were using Photoshop 3, you weren’t forced to upgrade to Photoshop 4 until you were ready. (Though other network effects, like sharing files sometimes forced the issue, but that’s a separate story). Something important was lost when we moved away from those clear versions.

Users lost the ability to control the disruption of relearning and adjusting to changes; developers lost the will to commit to revolutionary change.

Yes, splitting versions, like we did with Basecamp Classic, isn’t without complication. But from someone who’s been through the experience, the complication is not only overstated, but the benefits have also been under explored.

Maybe it’s time to ask yourself: What could we do if we weren’t afraid of revisiting the fundamentals of our software? What if we just did a new version and kept supporting the old one too? 2.5 years after we committed to this strategy, we remain happy with this rarely chosen path.