David Omoyele of Ink Audio read REWORK and had a beef with a passage in the book that suggests big companies don’t teach. He sent an email pointing out three examples to prove his point: 1) Apple offers free workshops at its retail stores. 2) Microsoft teaches via online lessons. 3) Gibson, one of the largest guitar sellers, offers “tone tips” like this one on how types of finishes affect the guitar’s tone.

More examples come to mind too: Nikon offers digital tutorials on its cameras. Dove conducts free Self-Esteem Workshop for Girls 8-12 years old designed to “promote new ways of thinking about beauty, body image and self-esteem.

So David’s got a point that big companies can and do teach.

Still, what percentage of these big co. budgets are going toward teaching vs. traditional marketing/advertising that hypes features? Big companies may be dipping their toes in these teaching waters but small businesses have a unique chance to dive in all the way and deliver more direct, personal lessons. And that can be a great way to turn customers into superfans. It remains one of those areas where small definitely has an advantage.

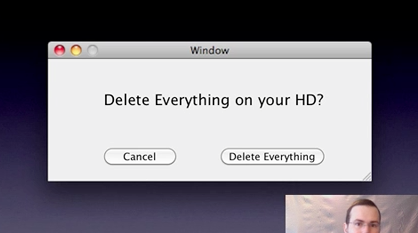

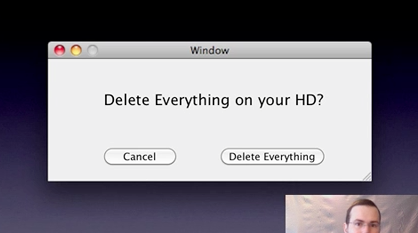

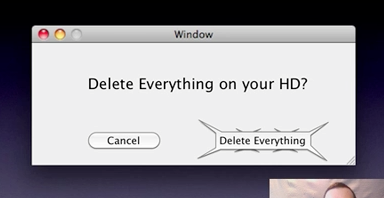

The Science of Aesthetics by Keith Lang (video) is a talk Lang gave at UXAustralia in 2009. In it, he talks about how some shapes are naturally friendly looking, like the rounded rectangle, while other shapes are harsher and more unfriendly. Here’s a cool example of how a UI could take advantage of this by using an aggressive, spiky shape:

Interesting idea. People would definitely think twice before clicking a button that looks like it’s going to carve up fingertips.

I recently spent a couple weeks in Japan, which is an amazing place for designers. There were thoughtful details everywhere I went. One example is the custom alarm clock in my Tokyo hotel (the Courtyard Marriott in Ginza).

This alarm is beautifully simple. There are only three buttons: decrement alarm time, increment alarm time, and on/off. The bottom row of buttons control the lighting of the room. (The white cable is from my iPhone charger, not part of the alarm).

I really like how the alarm time isn’t hidden behind a mode. The alarm time appears beside the current time in orange LED whenever the alarm is on. It doesn’t replace the current time, so you don’t have to track which mode is active. The two times look different from each other. The orange letters also give confirmation that the alarm is in fact set (which can be a concern when you rely on an unfamiliar device to wake you up).

When the increment/decrement buttons are held, the current time disappears to focus on the alarm time.

One of my favorite details is something you can’t see in these photos. The alarm is a solid brick of metal. It’s black and heavy, with no branding or seams visible anywhere. Solid, unobtrusive, and perfectly optimized—that’s a good design.

I don’t commute. I work from home. And I love it. I think of it as getting an extra hour a day. Add that up over the years and it’s a huge chunk of my life that’s given back to me. Not to mention the emotional toll that’s saved from not doing a rush hour commute, especially one on public transportation. (I still have flashbacks to the #66 Chicago Avenue bus I used to take to our office, including the one time – at 10am – a guy started snorting coke off his bus pass while sitting next to me.)

The toll that commuting can have on you is discussed in this article at BusinessWeek. It mentions “the commuting paradox” and why the trade-off of a long distance commute is rarely worth it.

Most people travel long distances with the idea that they’ll accept the burden for something better, be it a house, salary, or school. They presume the trade-off is worth the agony. But studies show that commuters are on average much less satisfied with their lives than noncommuters. A commuter who travels one hour, one way, would have to make 40% more than his current salary to be as fully satisfied with his life as a noncommuter, say economists Bruno S. Frey and Alois Stutzer of the University of Zurich’s Institute for Empirical Research in Economics. People usually overestimate the value of the things they’ll obtain by commuting – more money, more material goods, more prestige – and underestimate the benefit of what they are losing: social connections, hobbies, and health. “Commuting is a stress that doesn’t pay off,” says Stutzer…Commuting is also associated with raised blood pressure, musculoskeletal disorders, increased hostility, lateness, absenteeism, and adverse effects on cognitive performance.

Seems like yet another reason to consider remote workers. Who wouldn’t want a team that’s filled with folks who are less stressed and more satisfied with their lives?

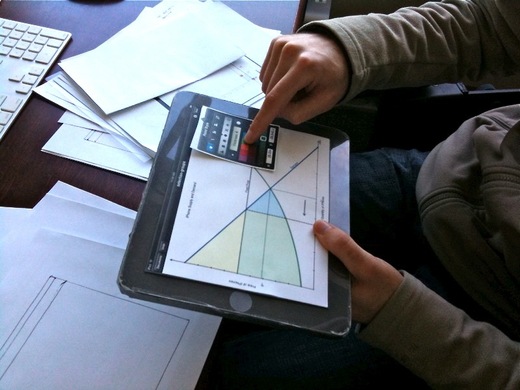

Re: the discussion of if/when to sell a company...

Incessantly maximizing profits and/or selling out doesn’t have to be the ultimate end goal. Sure, you want to get to a point where you’re profitable and comfortable. But then things get a bit more nuanced. Then it depends on what your priorities are.

What if you could make money, maybe not crazy numbers but still a healthy profit, selling a product that people really love? How much of a turn-on would that be to you (even if it means less profits than you’d make churning out a mediocre product)? How much would you be willing to shave off your bottom line to feel like you’re making something that genuinely makes a difference in people’s lives? How much is it worth to you to get emails from customers that tell you how much they love what you make?

Ego and pride can matter too. Can you put a price on the thrill you get from becoming a master at something and seeing the results in your efforts? What’s it worth to you to be able to proudly show your child what you work on every day? How much would someone have to pay you to walk away from that?

And what if you feel like you keep getting better at what you do every day? Even masters will tell you, you never have it all figured out. You’re always learning more. Refining. Getting better. And that can be intoxicating. When you feel like you keep building a better version of what you sell, it’s tough to walk away.

There are all different kinds of currency in life. Numbers in a bank account are just one of them.

On April 19 two new people will be joining 37signals.

Scott Upton: Designer

Scott Upton will be (re)joining us as a UI designer. Long time 37signals followers may recognize Scott’s name. Scott worked with 37signals for a few years back when we were a web design firm (before we launched Basecamp). He’s one of the best web UI designers in the business. Great writer too. We’re lucky to be able to welcome him back to 37signals. To top it all off, he’s a genuinely great person. He’s also quite a mountain climber and backcountry adventurer. Check out some of his adventures and photos at http://couloir.org.

Scott completes our design and development team. We don’t have plans to expand this group any time in the foreseeable future. We’re really happy with our crew. They’re great people. We’re proud to have them all.

Kiran Max Weber: Support

Kiran Max Weber will be joining us to head up the support/service group. Kiran’s a really sharp (and nice) guy with the background experience we need to build and maintain a world-class support team. He was a lead Mac Genius at the Fifth Avenue Apple Store in NYC. He helped supervise their 100-person Mac Genius team and acted as the point of contact for customer service escalations and front line support. He also has a design background and speaks English (thankfully), German, and basic French. He’ll be working closely with Sarah and Michael to make customers happy, maintain high support standards, handle escalations, keep tabs on major issues, review and improve our customer interactions, and answer customer questions.

While our design and development group is complete, our service and support group will be expanding over time. This is the one part of our business that needs to scale with our customer base. Kiran’s going to help us 1. make the right choices along the way and 2. be the best in the business.

Welcome

I hope you’ll join us in welcoming Scott and Kiran.