Inspiration and wealth will come to you if your goal is to help another person solve a problem.

Bootstrapped, Profitable, & Proud: Braintree

Braintree’s Bryan Johnson will answer your questions in the comments section.

In 2003, Bryan Johnson (right) was hired for a commission-only job selling credit card services to businesses. “I was broke,” says Johnson. “The job was brutal. Business owners were tired of the industry’s deception and trickery and didn’t hesitate when given an opportunity to vent.”

In 2003, Bryan Johnson (right) was hired for a commission-only job selling credit card services to businesses. “I was broke,” says Johnson. “The job was brutal. Business owners were tired of the industry’s deception and trickery and didn’t hesitate when given an opportunity to vent.”

Johnson quickly excelled, though. He became the top salesperson out of 400 nationwide and broke the existing sales record during his first year. His secret? “I simply figured out that businesses were looking for thee things: honesty, education and reliable service. I filled that gap and was received warmly. I also worked my tail end off.”

But by 2007, Johnson was sick of working for a big corporation. He says, “I concluded that I’d rather live poor and hungry than work in a large, bureaucratic and political environment where I personally couldn’t see how my efforts created value.”

He started figuring out what it would take to do his own thing. “I figured that I needed to make at least $2,100 a month to leave,” he explains. “My wife and I had learned to live quite frugally. I had started a few other businesses before, so this uncertainty and financial risk was something I was accustomed to. I had a single objective: Get back into the saddle. I was going to do whatever it took to get there.“

He took a few days off work and flew out to Utah, where his old customers resided. He asked them if they’d switch their processing to his new company, Braintree. Quite a few of them did, collectively generating $6,200 a month. Braintree was officially up and running.

Premium, not freemium

Early on, Johnson decided to stay away from the freemium model so popular among tech companies. “My experience in the payments industry told me it wasn’t for Braintree,” he explains. “We offer exceptional service during the sales and application process that continues after a merchant is set up with us. This level of service is too costly for a free account.”

So Braintree went the opposite route and charged a premium. It started with a $200 monthly minimum, which it’s since lowered to $75. “At $200, our minimum was 4 to 8 times higher than our competitors,” says Johnson. “Applying a floor helps the right kinds of customers self-select our services. After all, we’re as interested in having the right customers as they are in having the right provider.”

Who are the customers Braintree decided to write off? “It was a fool’s errand to try selling medicine to those who hadn’t yet experienced pain. Payment processing is complex. It’s difficult for inexperienced merchants to recognize value. We’d spend countless hours trying to explain ‘pain’ and our cure but some just didn’t care because they hadn’t felt it yet. With our limited resources, we had to figure out a way to work only with those who valued the medicine we were offering.

“We did take some grief for our higher minimums, but when we did, we’d politely explain that there were other, less expensive options in the industry, which may have been a better fit. I think staying firm often created an inverse effect, causing people to value us more than they did initially.”

Revenue growth

The formula is working so far. In 2010, Braintree generated $4.5MM in revenue, grew from 15 to 24 employees (now over 30), and doubled its customer base, according to Johnson. It powers payments for companies like LivingSocial, Github, OpenTable, and Animoto. And 99% of its customers come through word-of-mouth. “We’re on track to do $8 or $9 million in revenue during 2011,” Johnson says. “We also expect to rank among the top 50 on this year’s Inc. 500 list.“

Johnson is quick to note the difference between Braintree and other emerging payment companies. He says, “Four of these companies have raised around $40 million each and have roughly 3-6 times the personnel we do.”

Johnson feels that necessitates a different approach. “For many, raising a lot of money is accompanied by baked-in assumptions for how a business should be built,” he says. “The playbook typically calls for a large executive team and a few layers of management, which is very expensive. I think VC-funded companies are more inclined to throw money and people at opportunities and problems. This approach works for some, but there are other ways to build a successful business. Growing on our own dollar has granted us the freedom to do what we want, when we want, and how we want.”

It also forces Braintree to embrace constraints. “Without outside capital, we have to make do with less,” says Johnson. “Constraints are a beautiful thing because they force creativity and precision. We don’t have the resources to throw after hit-or-miss hires or strategies. Bootstrapping a business requires a different mentality. It’s taught us to be frugal, hire slowly, and exercise caution as we grew the business. While companies that take funding can do those things, people have a tendency to behave differently when it’s not their money on the line.”

“People have a tendency to behave differently when it’s not their money on the line.”Continued…

37signals company-wide meetup in Chicago is underway.

How an Illinois rest stop inspired a web page

Last summer I was driving back to Chicago from Wisconsin. On the Illinois side there are a couple of rest stops over the tollway. It’s a great place to get some gas, grab some caffeine, and stretch your legs a little before the final 50 miles home.

The rest stop usually has a booth where you can buy a iPass so you don’t need to stop and pay tolls all the time. During the day the booth is manned by someone to help answer any questions you have.

It appears that a lot of the same questions are asked over and over. Enough, in fact, that the dude who answers them is sick of giving the same answer. That answer is “Yes”.

So he jumped on a computer somewhere and put together what I can only describe as one of the smartest formats for an FAQ I’ve ever seen. A single answer on top, and all the questions below. The answer is always YES!! YES, YES. YES!! Then he taped it to the outside of the booth. You can’t miss it.

I thought this was brilliant. I just love it. Yeah, it’s full of passive aggression and spelling errors and formatting problems, but the idea in itself is so refreshing. It’s folk information art.

Inspired by this, we whipped up our own version of a YES! page for Highrise. It was a fun exercise in messaging and design.

Continued…What to look for in a UI designer

There’s a thread on Quora about how to define a designer’s ideal range of knowledge.

Here are the dimensions we look at:

- Writing: Can they think and communicate clearly? Writing skills are critical to UI.

- Interface design: Can they organize elements in 2D space so that the arrangement is meaningful, clear, and instantly understandable? Can they organize elements in time (navigation, flows, steps) in a way that minimizes uncertainty and feels efficient?

- Product: Can they appreciate the problems and desires our customers have and turn that understanding into business value? In other words, do they know what matters and what doesn’t matter to customers and stakeholders?

- Development: Are they able to code their designs in HTML/CSS? Can they go further and integrate their designs into the application source code? Can they talk shop with programmers?

- Character: Are they a nice person with a good motivation?

Of course it isn’t necessary for everyone to kill on every point (except #5). But I think you can tell a lot about a company’s design culture by looking across these dimensions.

Exit Interview: Farhad Mohit of Shopzilla

Exit Interview is a new Signal vs. Noise series that talks to founders to see what happens after companies get acquired.

“We’re betting that Shopzilla will become the way that people shop online,” said Kenneth W. Lowe, president and CEO for EW Scripps in June of 2005, after the company bought Shopzilla for $562 million in cash. Shopzilla co-founder Farhad Mohit echoed, “With Scripps and its lifestyle brands, media assets and financial resources backing our team and vision for building the ultimate shopping service, we are assured of the chance to continue building Shopzilla into a site that consumers worldwide will choose every time they want to shop online.”

“We’re betting that Shopzilla will become the way that people shop online,” said Kenneth W. Lowe, president and CEO for EW Scripps in June of 2005, after the company bought Shopzilla for $562 million in cash. Shopzilla co-founder Farhad Mohit echoed, “With Scripps and its lifestyle brands, media assets and financial resources backing our team and vision for building the ultimate shopping service, we are assured of the chance to continue building Shopzilla into a site that consumers worldwide will choose every time they want to shop online.”

But it didn’t take long for the partnership to sour. Mohit now says, “It became obvious to me that Scripps was more interested in milking the search engine marketing arbitrage cash-cow that we had created, than in going after true customer loyalty by offering a universal shopping cart enabled service that could take on Amazon.”

Mohit was also disappointed that Scripps didn’t offer more incentives to the Shopzilla team. He says, “In order to execute on the big vision, I told corporate that they would have to put aside a good sized employee pool tied to Shopzilla’s performance (not Scripps performance overall which we could not really affect) and to give a healthy percentage of the upside to our employees, financially incentivising everyone to bust ass to take us from a $500 million company to a $5 billion one.

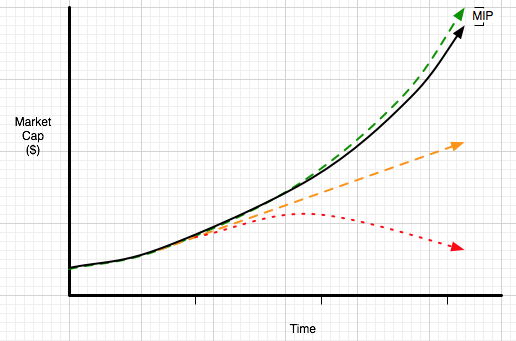

“I remember telling them that even if they give $1 billion to the employees, if they ended up with a $5 billion company it would be worth it. I illustrated this with a simple graph that showed three possible trajectories that corporate could bet on happening, depending upon how well they kept their best and brightest engaged.

"They declined to offer a significant ‘MIP’ — Management incentive Plan — and they ended up right in between the orange and red lines."

Parting ways

By Febuary of 2007, Mohit had seen enough and left. "When I saw that our vision was not going to be executed and that our corporate parent was more interested in managing costs, there was not much reason to stay any longer." Mohit, Henry Asseily (CTO and co-founder), and John Phelps (CEO at the time and employee #8) all quit at the same time.

"Innovation essentially came to a standstill after the sale and has continued to be frozen for years," according to Mohit. "In nominal terms, they are just as well off. But in relative terms, given all the innovation that has taken place in the commerce landscape, and the advent of social, mobile, local, and online-to-offline commerce, I feel that Shopzilla totally missed the opportunity to build a monster franchise."

Continued…A Letterpressed Thank You

I recently designed some 37signals Thank You cards. They were printed by Rohner Letterpress in Chicago. Here’s what they look like:

It was a really fun to see a working letterpress. I have done offset printing before, but this was my first time seeing a letterpress in action. I made a fun little video of the press — heavily inspired by Steve Delahoyde’s awesome Field Notes videos. Original music by Sudara.

Update: Here’s a link to download the song Sudara made.

We sent out a batch for those kind enough to participate in our Holiday Toy Drive.

How to get good at making money

This month’s Inc. cover story: Jason Fried on how to get good at making money.

I got FileMaker Pro (I paid for it with the stash I’d saved up selling stuff to my friends) and started messing around. After a few months, I had solved the problems I had with organizing my music. I knew what music I had, where it was, whom I had loaned it to, how much I paid for it. The solution was elegant and easy to use. I called it Audiofile…Before making it available to other AOL users, I added a limit in the program—people could file 25 CDs for free; after that, it would cost $20 to unlock Audiofile and remove the limit.

I remember my first customer. One day my parents gave me an envelope. It came from Germany and had those airmail stripes at the top. I opened it up, found a screenshot of Audiofile printed on a piece of paper—and a crisp $20 bill. More envelopes rolled in. Over the next few years, Audiofile probably generated $50,000—not bad for a kid in college in the early ‘90s.

The lesson: People are happy to pay for things that work well. Never be afraid to put a price on something. If you pour your heart into something and make it great, sell it. For real money. Even if there are free options, even if the market is flooded with free. People will pay for things they love.

Read the rest.

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works. Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it. Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

Douglas Adams, “The Salmon of Doubt”