While talking to Grant Petersen from Rivendell, he mentioned his love of decades old Chouinard climbing catalogs.

I grew up reading catalogs. The Herter’s catalogue* was the most opinionated one out there, but it was also the most entertaining. Sometimes I’ll read an online comment that, “Rivendell (or Grant) is so opinionated” and it’s supposed to be a criticism. It’s not a criticism. If you want to criticize me, there are way better ways to do it. Tell me I don’t have my facts right, or I don’t give credit where it is due, or my grammar is bad, or my jokes are stupid. That will do the job of hurting my feelings, but being accused of being opinionated is a compliment.

The best catalogues ever were the 1972 and 1973 Chouinard Equipment/Great Pacific Iron Works climbing catalogs. There will never be catalogues like those again. Everybody who writes copy or catalogs or online stuff or reads at all should read those.

Strong praise. Turns out the 1972 Chouinard Catalog is online. Copies of the original catalog fetch $200+ on eBay. But to understand its impact, you first need to know the context around it.

The Chouinard backstory

The backstory to the company is a “scratch your own itch” tale. It starts with pitons, the metal spikes climbers drive into cracks. They used to be made of soft iron. Climbers placed them once and left them in the rock.

But in 1957, a young climber named Yvon Chouinard decided to make his own reusable hardware. He went to a junkyard and bought a used coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil, some tongs and hammers, and started teaching himself how to blacksmith. He made his first chrome-molybdenum steel pitons and word spread. Soon, he was in business and selling them for $1.50 each to other climbers. By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the U.S.

But there was a problem. The company’s gear was damaging the rock. The same routes were being used over and over and the same fragile cracks had to endure repeated hammering of pitons. The disfiguring was severe. So Chouinard and his business partner Tom Frost decided to phase out of the piton business, despite the fact that it comprised 70% of the company’s business. Chouinard introduced an alternative: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks. They were introduced in that 1972 catalog, the company’s first. The bold move worked. Within a few months, the piton business atrophied and chocks sold faster than they could be made.

Looking at the catalog

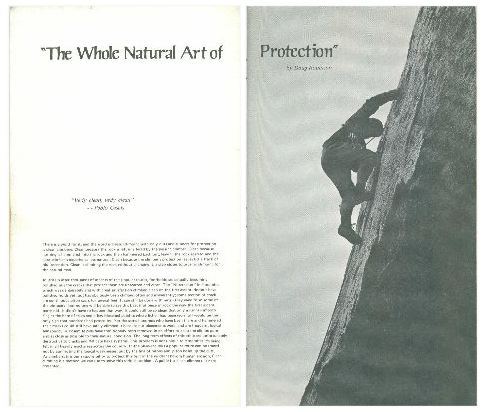

So what kind of catalog do you put out when you’re reversing your entire business? Chouinard went with a mix of product descriptions, climbing advice, inspirational quotes, and essays that served as a “clean climbing” manifesto. It opens with a statement on the deterioration of both the physical aspect of the mountains and the moral integrity of climbers.

No longer can we assume the earth’s resources are limitless; that there are ranges of unclimbed peaks extending endlessly beyond the horizon. Mountains are finite, and despite their massive appearance, they are fragile…

We believe the only way to ensure the climbing experience for ourselves and future generations is to preserve (1) the vertical wilderness, and (2) the adventure inherent in the experience. Really, the only insurance to guarantee this adventure and the safest insurance to maintain it is exercise of moral restraint and individual responsibility.

Thus, it is the style of the climb, not attainment of the summit, which is the measure of personal success. Traditionally stated, each of us must consider whether the end is more important than the means. Given the vital importance of style we suggest that the keynote is simplicity. The fewer gadgets between the climber and the climb, the greater is the chance to attain the desired communication with oneself—and nature.

The equipment offered in this catalog attempts to support this ethic.

A guide for clean climbers.

A few pages later, there is a guide for clean climbers.

Continued…There is a word for it, and the word is clean. Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing. Clean because the rock is left unaltered by the passing climber. Clean because nothing is hammered into the rock and then hammered back out, leaving the rock scarred and next climber’s experience less natural. Clean is climbing the rock without changing it; a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man.