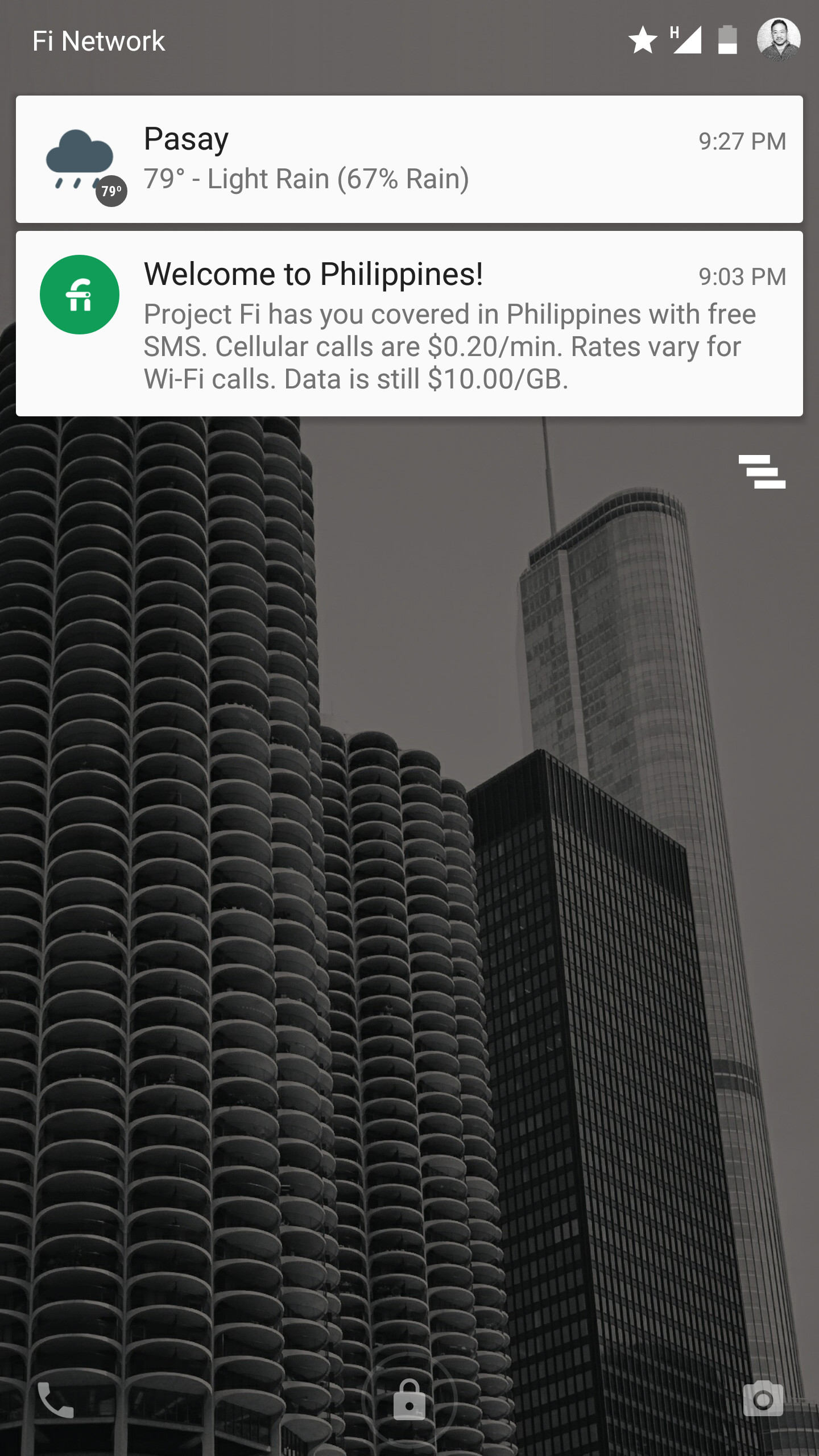

A few months ago I was invited to join Project Fi, Google’s wireless carrier experiment. International Data (certain countries) is included with your plan. There are no extra fees for SMS or data usage.

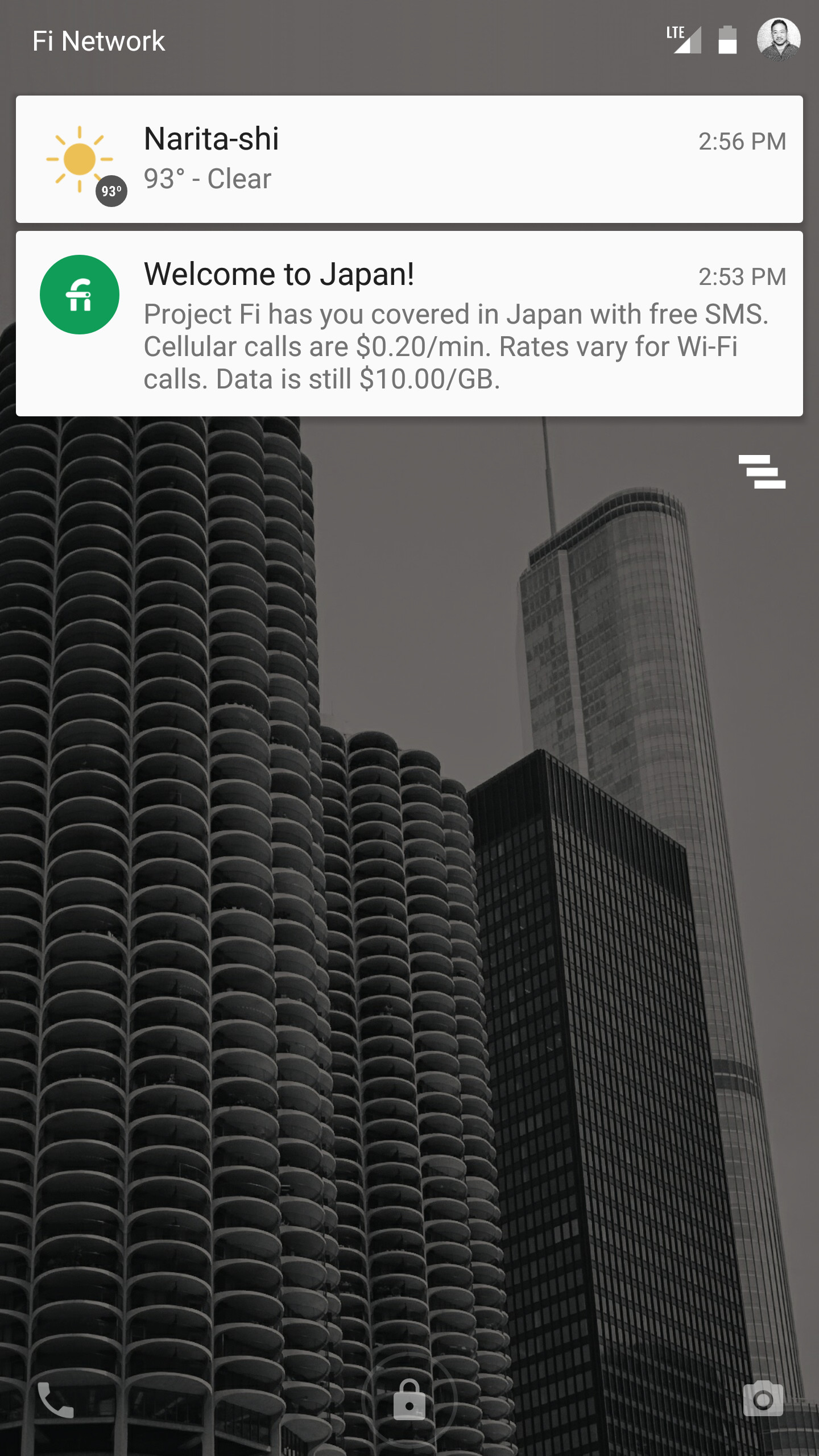

Project Fi reminds you of this benefit with a nice notification once you turn off Airplane Mode after landing.

Here’s what I got when I landed at Ninoy Aquino International Airport in the Philippines.

The Welcome to [Country]! is a nice way to start off the notification. Here’s what I got when I landed at Narita International Airport in Japan.

The folks at Project Fi know I’ll be taking my phone out of Airplane Mode. They know I’m in a different country. A notification is small thing, but context and timing is everything.

Something's coming 2

Something's coming

It Soothes, It Heals, It Tingles

Alfred Woelbing made the first batch of Carmex at his kitchen stovetop in 1937. He was looking for a cold sore treatment and came up with a hit lip balm instead. Nearly 80 years later, Carma Labs is still family-owned and run by Alfred’s grandson, Paul, a former art teacher. In this episode of The Distance, find out what goes into the Carmex formula—both for making lip balm and for building a company that takes care of its customers and employees over the long term.

We are making a push to build up our audience this summer, and we’d love your help in spreading the word out about The Distance. If you’re enjoying our stories, please tell your friends about our show and encourage them to subscribe via iTunes or whichever podcatcher app they use. Thanks!

"Is it too early for me to start a pay-per-click campaign?"

My SaaS product is done. We have a customer who we reached out to locally. I’ve got a freelance writer (via Reddit!) who is working on creating an email course to educate and inform potential customers. Until that is done there is nowhere for me to collect email addresses and start warming them up. However, I do have pricing and plans and the sign up is fully implemented. Is it worth creating a couple ads to start generating some traffic yet? Or is it going to be a complete waste of time until I have that ecourse and am able to collect email addresses? If I do create ads now is it critical to also have a landing page for each?

For over 12 years, I’ve run paid ad campaigns on popular channels like Google and Facebook, but also less known advertising channels like Reddit and Plenty of Fish. I’ve used those ads to get people to buy software, play online games, even buy flip flops my Mom handmakes. I’ve learned a ton about optimizing click through rates, landing pages, ad budgets, etc.

And those lessons have been super valuable. When we redid the Highrise marketing site I had a ton of lessons and tools at my disposal to help optimize our conversions. By changing layouts, copy, buttons, headlines, and testimonials, we doubled our conversion rate.

Nothing is a waste of time if done to learn a new skill. If you read any of the books on learning, like Talent Code, the trick is to practice deliberately and in small feedback loops that don’t kill you. Do you know much about paid ads and conversion optimization? Then that’s a great way to learn about them. Just time box it. Don’t spend many resources on this step.

See, I’ve also used these same skills to recruit thousands of users to a new business I started in 2011. Optimized the bejesus out of our ads on places like Reddit. We were getting super high conversion rates on our landing pages.

But here’s the rub. How many of those tens of thousands of people whom we recruited are now following what I’m doing at Highrise or Draft? How many of them follow my blog or what I have to say on Twitter? How many of those people whose attention I paid for in 2011, are helping me with my goals today?

None.

Even though I encourage experimentation with pay-per-click ads and landing page optimization, often their pursuit doesn’t get us very far.

Ads for most products in most industries are just way too saturated. It’s become a break even game of advertisers paying so much for a click, that they convert just enough customers and given the lifetime value of the customer, they make their ad budget back. But they look so tempting. It’s a fun puzzle to solve. If you could just find that overlooked keyword+product combo, you could just scale that up and profit.

But these players also know their customer’s lifetime value. They know how many new users each paid user recruits. They get the type of traffic they can use to get significant statistical samples to split test every button, headline, and word. The people winning the ad game can play with a sophistication to make their ad budgets back plus profit, and still the results are usually temporary as new entrants and click fraud push click prices higher and higher.

But many of us who are on our first product or even our tenth product don’t have all these things figured out yet.

So instead of spending much time on optimizing landing pages and ads, I’d spend more time on what Paul Graham would say: Things that don’t scale.

You mentioned having one customer, now go get 10. Call them. Meet at their office. Go give them a demo in person. Review their results with them slowly and methodically. This stuff doesn’t scale. You aren’t going to want to make this the way you get big, but one customer is often not enough. If they are the only one in your ear about features you need, you’ll probably be too inclined to make a specific thing that just fits their needs. I created Inkling as part of Y Combinator in 2005, and we were constantly in this state in the beginning. We would have one big customer paying us a hefty amount of money, but then the requirements they had were incredibly specific and not at all applicable to other clients down the road. Once we started getting that slightly bigger sample size, the commonalities were much easier to spot, and we could focus on those. It became a lot easier to make the right things the next customer needed, and build a product that would actually work as a business.

I’d also focus on teaching. Read everything Kathy Sierra talks about on the topic – actually, just read everything she’s written. Here’s a great place to start: Out teach your competition.

Your email course is a great idea. But you are right, you have no one to email. So where else can you get yourself teaching people. Are you writing a blog? Running a podcast? Doing any interviews with other teachers in this industry? What about trying to get some articles published in magazines? Hosting a meetup?

What’s great is how all this teaching can be repurposed for different places. Turn the email course into a video blog. Turn it into a set of lessons on Vine. Take pictures and use Instagram to share the lesson.

Gary Vaynerchuk does a great job of this. Every lesson can be repurposed and told using the strengths of another channel. Check out how he uses Instagram to teach.

Again, this stuff is often going to feel like it doesn’t scale. It’s a slog. And it doesn’t immediately convert to new customers and automatic wealth. But the payoff is in the long game. Start building an audience. Your product is going to go through dozens of iterations. Maybe it doesn’t even work out. But that audience? They’ll follow you to the next iteration, or the next project.

I wish this was the view I had taken when I was building that business in 2011. The money and time I spent could have been spent building an audience who could be helping me with today’s challenges.

Congratulations on your product. That is an awesome first step. Have fun! And keep the momentum going! Most people can’t even get something out the door. The fact though now is, most of our first products fail. We didn’t make them right. Or they’re missing something critical we didn’t realize we overlooked. Or in two years, you realize you need to pursue something different.

So, I’d be careful about trying to optimize something like pay-per-click ads, and landing pages. Those are often just local maxima, meaning you might improve something about it and it feels like a small win, but there’s probably a much bigger win to find if you open up your gaze on the life of your product and career as an entrepreneur. It’s hopefully a career you are going to be growing for a very long time.

(A version of my answer originally appeared on Reddit.)

P.S. If I can be of service at all to anyone, please let me know. Would love to help any way I can. Twitter is a great place to reach me. You should follow me: here.

A mountain of salt for the Apple Watch satisfaction numbers

We’ve talked a lot about the Apple Watch internally, and even thought a bit about how Basecamp might work on it. A number of Basecampers have gotten Apple Watches, and reviews have been mixed; some people returned their watch, others wear it every single day. Our unscientific, non-representative sentiment runs probably 50/50 satisfied/dissatisfied with the watch.

A study reporting high levels of customer satisfaction with the Apple Watch made the round of news sites last week, from the New York Times to Fortune to re/code. The same study was also mentioned by Tim Cook on the most recent Apple earnings call. The study was conducted by Creative Strategies, Inc for Wristly, and you can read the whole report on their website.

I’ve never touched an Apple Watch, and I personally don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it. Even so, when I see a study like this, especially one that receives so much press attention and that runs contradictory to other data points (such as the reactions from my colleagues), my attention turns to understanding more about the details of how they conducted the study and drew their conclusions. Examining this study in more detail, I find four major reasons to be skeptical of the results that received such media interest.

Are these apples and oranges?

One of the most talked about conclusions from this study was that the Apple Watch had a higher satisfaction level than the iPhone and iPad had following their introduction in the market. This conclusion is drawn by comparing the “top two box” score from Wristly’s survey (the portion of consumers reporting they were “very satisfied/delighted” or “somewhat satisfied” with their watch) against satisfaction scores from surveys conducted by ChangeWave Research in 2007 and 2010.

Without going into the quality of those original surveys, there are two clear differences between the Apple Watch research and the iPad and iPhone surveys that make this sort of comparison specious:

- Different panels: in order for this sort of comparison to be useful, you’d need to ensure that the panels of consumers in each case of roughly equivalent – similar demographics, tech familiarity, etc. There isn’t really sufficient information available to conclude how different the panels are, but the chances that three very small panels of consumers gathered over an eight year span are at all similar is exceedingly low. A longitudinal survey of consumers that regularly looked at adoption and satisfaction with new devices would be fascinating, and you could draw some comparisons about relative satisfaction from that, but that isn’t what was published here.

- Different questions: the Apple Watch survey asked a fundamentally different question than the earlier work. In Wristly’s survey, they appear to have measured satisfaction using a five point Likert-type scale: they had two positive and two negative rankings surrounding a fifth neutral ranking. By way of contrast, the ChangeWave research for both the iPhone and iPad used a four-point Likert scale (two positive and two negative ratings with no neutral ground) with a fifth “don’t know” option. The question of whether a four or five point scale is a better choice isn’t necessarily settled in the literature, but it’s obvious that the top-two-box results from the two aren’t directly comparable.

Who are you asking?

The conclusions of a survey are only as good as the data you’re able to gather, and the fundamental input to the process is the panel of consumers who you are surveying. You want a panel that’s representative of the population you’re trying to draw conclusions from; if you’re trying to understand behavior among people in California, it does you no good to survey those in New York.

There are a lot of techniques to gather survey panel members, and there are many companies dedicated to doing just that. You can offer incentives for answering a specific survey, enter people into a contest to win something, or just try talking to people as they enter the grocery store. Panel recruitment is hard and expensive, and most surveys end up screening out a large portion of generic survey panels in order to find those that are actually in their target population, but if you want good results, this is the work that’s required.

Wristly’s panel is an entirely opt-in affair that focuses only on Apple Watch research. The only compensation or incentive to panel members is that those who participate in the panel will be the first to receive results from the research.

It’s not hard to imagine that this sort of panel composition will be heavily biased towards those that are enthusiastic about the watch. If you bought an Apple Watch and hated it, would you choose to opt-in to answer questions about it on a weekly basis? I wouldn’t. (Credit to Mashable for noting this self-selection effect).

To Wristly’s credit, they do attempt to normalize for the background of their panel members by splitting out ‘Tech insiders’ from ‘Non-tech users’ from ‘App builders’ from ‘Media/investors’, which is a good start at trying to control for a panel that might skew differently from the general population. Even this breakdown of the data misses the fundamental problem with an opt-in panel like this: the massive self-selection of Apple Watch enthusiasts.

What’s the alternative? Survey a large number of consumers (likely tens of thousands) from a representative, recruited panel; then, screen for only those who have or had an Apple Watch, and ask those folks your satisfaction questions. This is expensive and still imperfect — recruited research panels aren’t a perfect representation of the underlying population — but it’s a lot closer to reality than a completely self-selected panel.

Where are the statistics?

The survey report from Wristly uses language like “We are able to state, with a high degree of confidence, that the Apple Watch is doing extremely well on the key metric of customer satisfaction” and “But when we look specifically at the “Very Satisfied” category, the differences are staggering – 73% of ‘Non Tech Users’ are delighted vs 63% for ‘Tech Insiders’, and only 43% for the ‘App Builders’”.

Phrases like “high degree of confidence” and “differences are staggering” are provocative, but it’s hard to assess the veracity of those assessments without any information about whether the data presented has any statistical significance. As we enter another presidential election season in the United States, political polls are everywhere and all report some “margin of error”, but no such information is provided here.

The fundamental question that any survey should be evaluated against is: given the panel size and methodology, how confident are you really that if you repeated the study again you’d get similar results? Their results might be completely repeatable, but as a reader of the study, I have no information to come to that conclusion.

What are the incentives of those involved?

You always have to consider the source of any poll or survey, whether it’s in market research or politics. A poll conducted by an organization with an agenda to push is generally less reliable than one that doesn’t have a horse in the race. In politics, many pollsters aren’t considered reliable; their job isn’t to find true results, it’s to push a narrative for the media or supporters.

I have no reason to believe that Wristly or Creative Strategies aren’t playing the data straight here—I don’t know anyone at either company, nor had I heard of either company before I saw this report. I give them the benefit of the doubt that they’re seeking accurate results, but I think it’s fair to have a dose of skepticism nonetheless. Wristly calls itself the “largest independent Apple Watch research platform” and describes its vision as “contribut[ing] to the Apple Watch success by delivering innovative tools and services to developers and marketers of the platform”. It’s certainly in their own self-interest for the Apple Watch to be viewed as a success.

So what if it’s not great research?

There’s a ton of bad research out there, so what makes this one different? For the most part, nothing — I happened to see this one, so I took a closer look. The authors of this study were very good at getting media attention, which is a credit to them — everyone conducting research should try hard to get it out there. That said, it’s disappointing to see that the media continues to unquestioningly report results like this. Essentially none of the media outlets that I saw reporting on these results expressed even the slightest trace of skepticism that the results might not be all they appear on first glance.

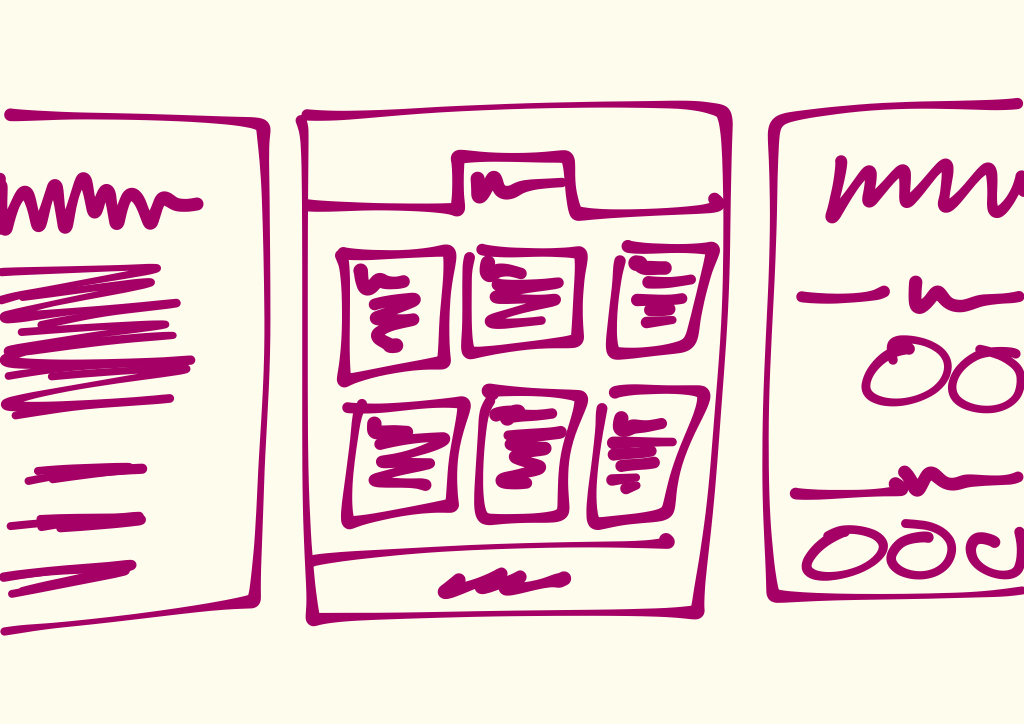

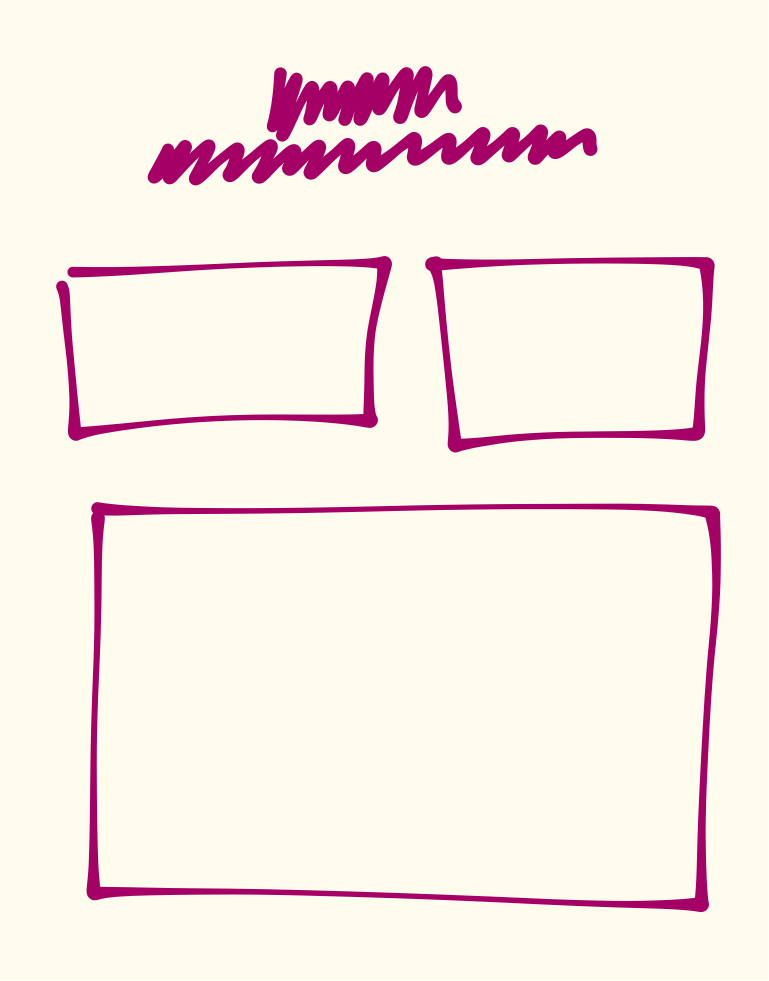

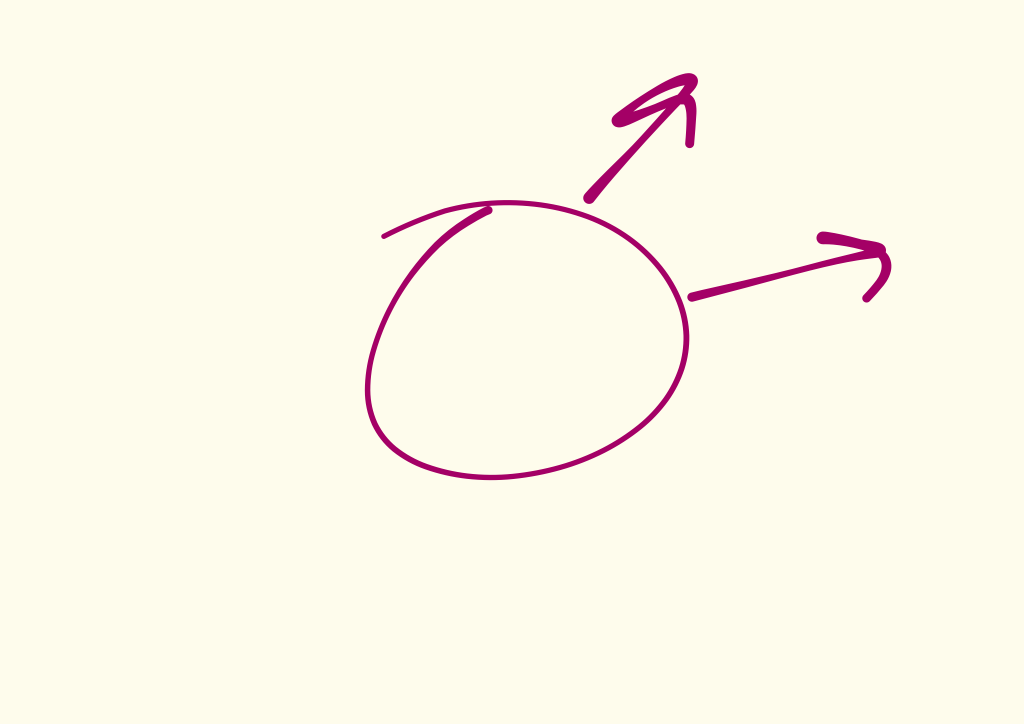

How an idea comes together for me

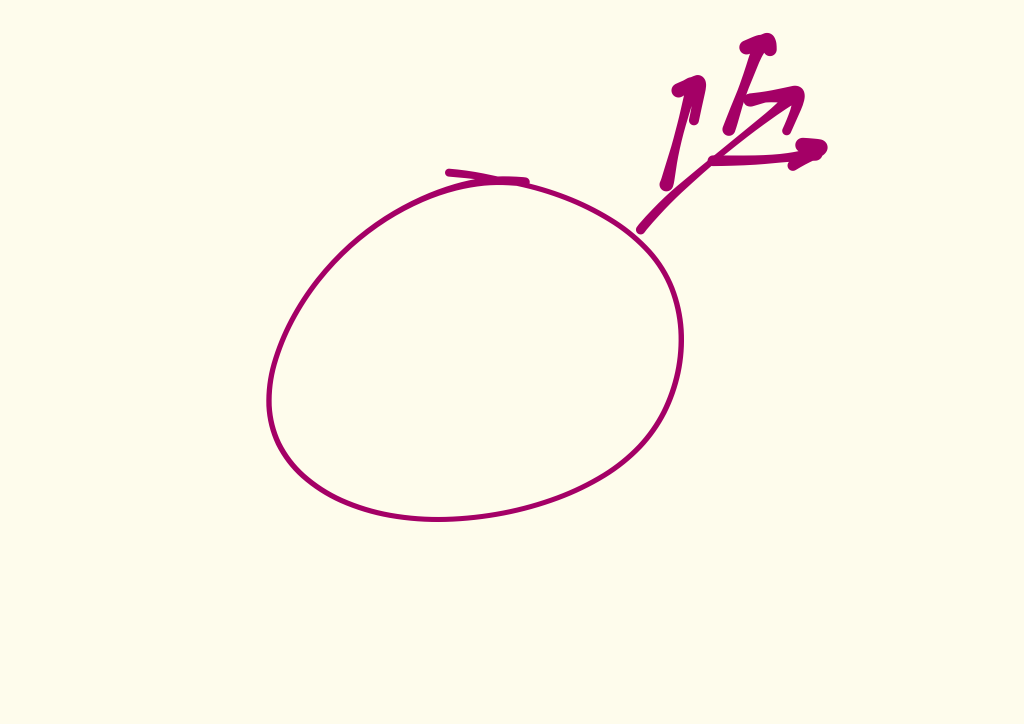

First the idea hits.

Then I think about it some more and it takes a direction.

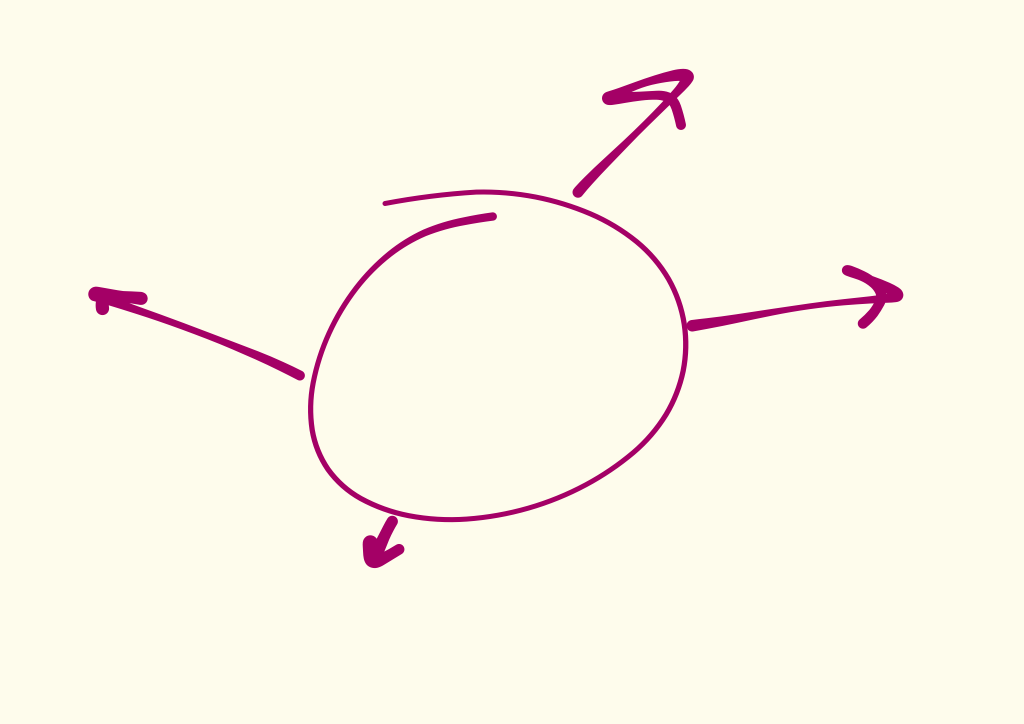

As I work through the direction, I’ll see another direction. Usually relatively similar, but different enough that it demands its own exploration.

As I dig in into the problem, more layers and possibilities reveal themselves. Sometimes they point in entirely different directions. Some seem like big possibilities, others seem smaller.

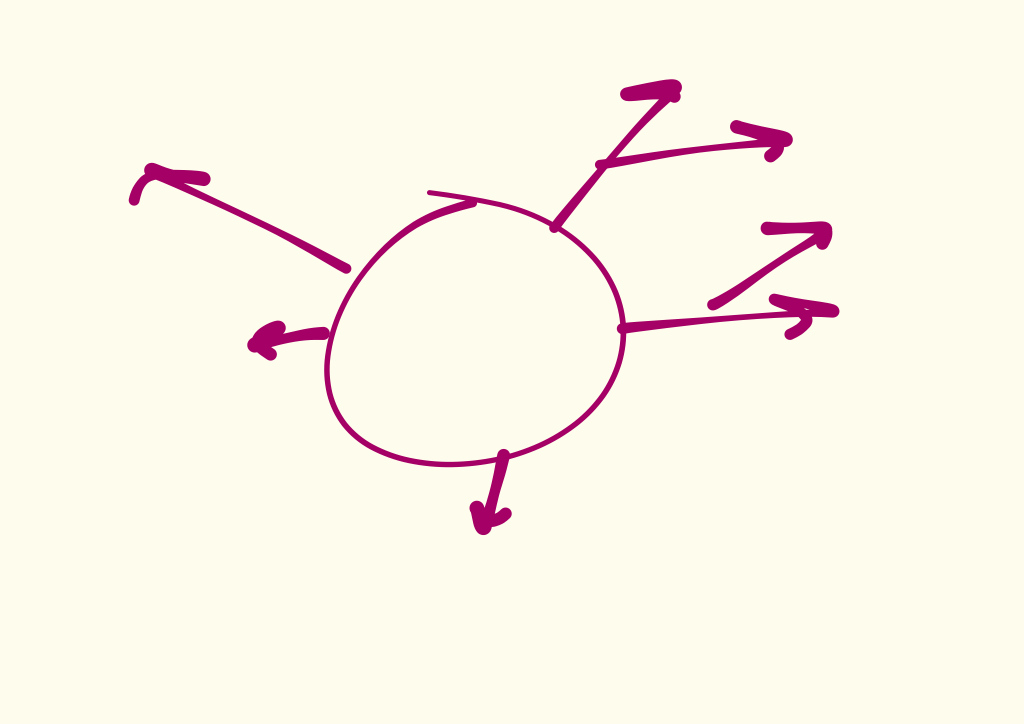

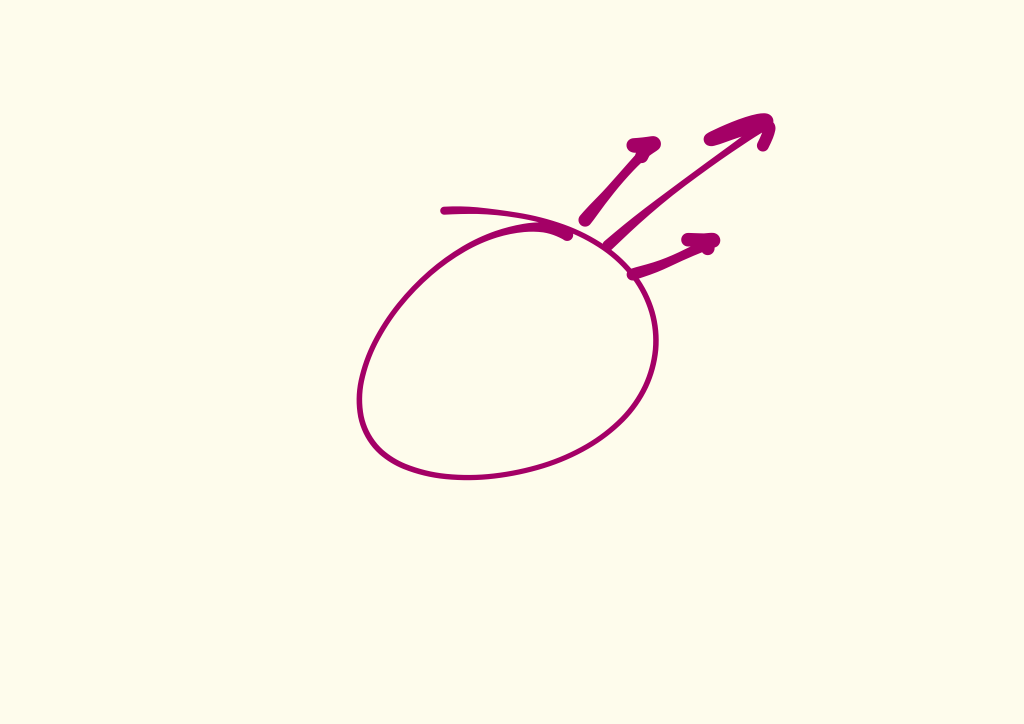

As I keep exploring, some more options emerge. Some independent of the ones I’ve already explored, but others branch off from an existing exploration.

As I keep sketching and thinking and mocking and working through variations and conditions in my head, on paper, or in code, a few strong possibilities take the lead. I begin to follow those.

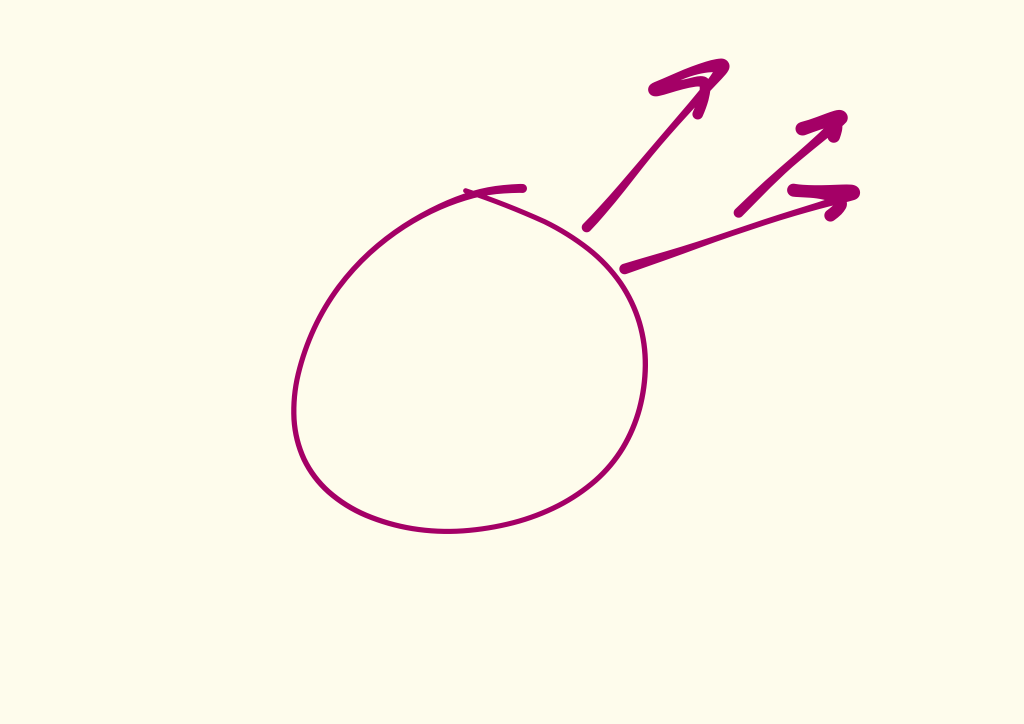

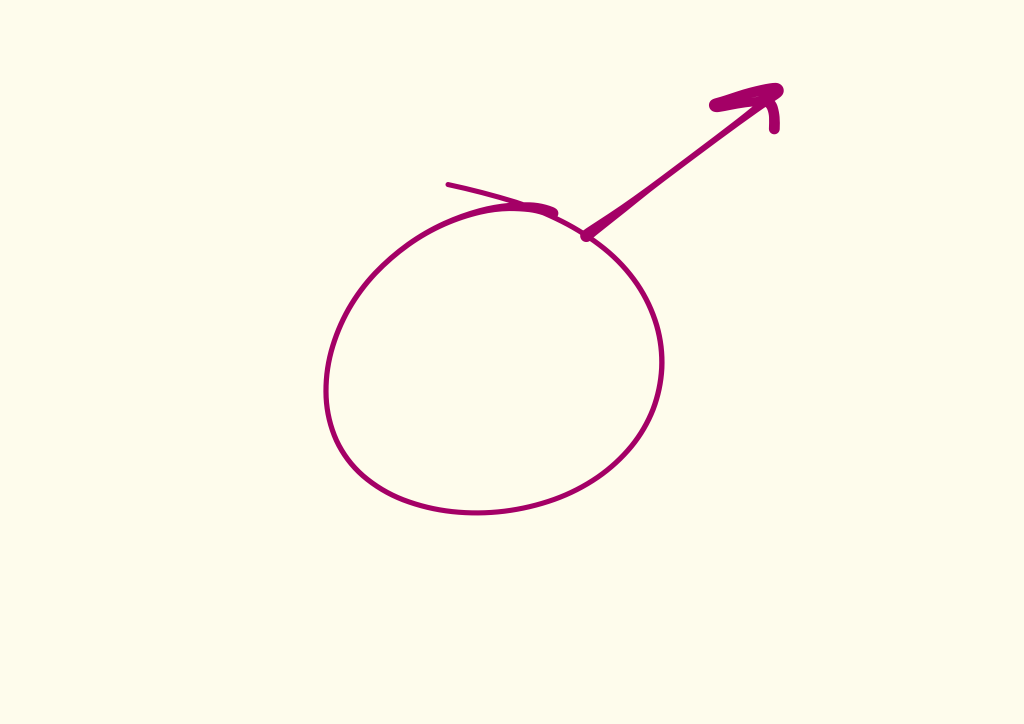

One primary direction becomes the most obvious, but there are still variations on that idea.

As I dig into the variations, I realize they aren’t direct descendants of that primary direction. Instead they’re closely related offshoots, but smaller. They usually fade away.

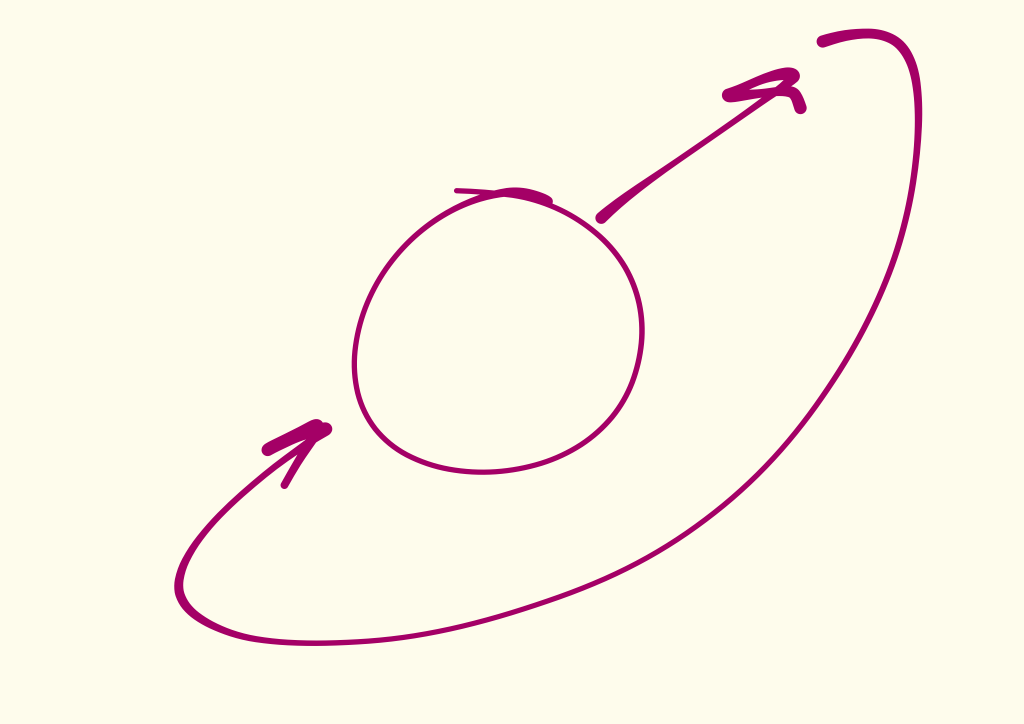

And finally the solution becomes clear.

Then I check my thinking by going through the process again.

Where it goes from here depends on what it is, but hopefully at the end I’ve enjoyed figuring something out.

Cheesecake, the Chicago Way

The latest episode of The Distance visits Chicago institution Eli’s Cheesecake, which produces the equivalent of 20,000 cheesecakes a day. What goes into a Chicago-style cheesecake? How about a 1,500-pound Chicago-style cheesecake? Listen to the episode to find out. And if you like the show, you can subscribe to The Distance via iTunes or the podcast app of your choice. We’ll be back in two weeks with another episode about a long-standing business.

What are people reading on SvN lately?

An organization, a social artifact, is very different from a biological organism. Yet it stands under the law that governs the structure and size of animals and plants: The surface goes up with the square of the radius, but the mass grows with the cube. The larger the animal becomes, the more resources have to be devoted to the mass and to the internal tasks, to circulation and information, to the nervous system, and so on.

Peter Drucker, The Effective Executive, 1967.