Exit Interview is a new Signal vs. Noise series that talks to founders to see what happens after companies get acquired.

“We’re betting that Shopzilla will become the way that people shop online,” said Kenneth W. Lowe, president and CEO for EW Scripps in June of 2005, after the company bought Shopzilla for $562 million in cash. Shopzilla co-founder Farhad Mohit echoed, “With Scripps and its lifestyle brands, media assets and financial resources backing our team and vision for building the ultimate shopping service, we are assured of the chance to continue building Shopzilla into a site that consumers worldwide will choose every time they want to shop online.”

“We’re betting that Shopzilla will become the way that people shop online,” said Kenneth W. Lowe, president and CEO for EW Scripps in June of 2005, after the company bought Shopzilla for $562 million in cash. Shopzilla co-founder Farhad Mohit echoed, “With Scripps and its lifestyle brands, media assets and financial resources backing our team and vision for building the ultimate shopping service, we are assured of the chance to continue building Shopzilla into a site that consumers worldwide will choose every time they want to shop online.”

But it didn’t take long for the partnership to sour. Mohit now says, “It became obvious to me that Scripps was more interested in milking the search engine marketing arbitrage cash-cow that we had created, than in going after true customer loyalty by offering a universal shopping cart enabled service that could take on Amazon.”

Mohit was also disappointed that Scripps didn’t offer more incentives to the Shopzilla team. He says, “In order to execute on the big vision, I told corporate that they would have to put aside a good sized employee pool tied to Shopzilla’s performance (not Scripps performance overall which we could not really affect) and to give a healthy percentage of the upside to our employees, financially incentivising everyone to bust ass to take us from a $500 million company to a $5 billion one.

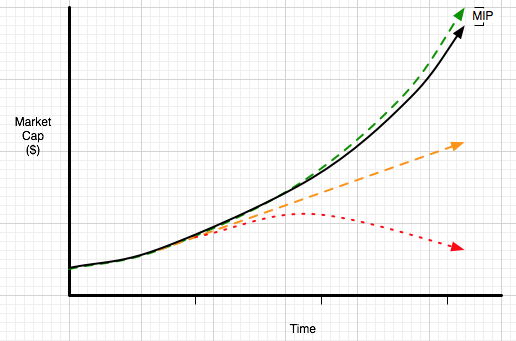

“I remember telling them that even if they give $1 billion to the employees, if they ended up with a $5 billion company it would be worth it. I illustrated this with a simple graph that showed three possible trajectories that corporate could bet on happening, depending upon how well they kept their best and brightest engaged.

"They declined to offer a significant ‘MIP’ — Management incentive Plan — and they ended up right in between the orange and red lines."

Parting ways

By Febuary of 2007, Mohit had seen enough and left. "When I saw that our vision was not going to be executed and that our corporate parent was more interested in managing costs, there was not much reason to stay any longer." Mohit, Henry Asseily (CTO and co-founder), and John Phelps (CEO at the time and employee #8) all quit at the same time.

"Innovation essentially came to a standstill after the sale and has continued to be frozen for years," according to Mohit. "In nominal terms, they are just as well off. But in relative terms, given all the innovation that has taken place in the commerce landscape, and the advent of social, mobile, local, and online-to-offline commerce, I feel that Shopzilla totally missed the opportunity to build a monster franchise."

Continued…

I got FileMaker Pro (I paid for it with the stash I’d saved up selling stuff to my friends) and started messing around. After a few months, I had solved the problems I had with organizing my music. I knew what music I had, where it was, whom I had loaned it to, how much I paid for it. The solution was elegant and easy to use. I called it Audiofile…Before making it available to other

I got FileMaker Pro (I paid for it with the stash I’d saved up selling stuff to my friends) and started messing around. After a few months, I had solved the problems I had with organizing my music. I knew what music I had, where it was, whom I had loaned it to, how much I paid for it. The solution was elegant and easy to use. I called it Audiofile…Before making it available to other  In late 2004, Daniel Baker (right) was a newly minted private pilot flying Cessna 172s around the country. “I wanted my friends and family to be able to track my flights just as they could if I were flying on a commercial airline,” explains Baker. “I may have been piloting the aircraft myself, but I still needed a ride once I landed. There were a few commercial products that provided this service for around $1,000 a month, but that wasn’t a realistic solution for friends and family. I got in touch with the

In late 2004, Daniel Baker (right) was a newly minted private pilot flying Cessna 172s around the country. “I wanted my friends and family to be able to track my flights just as they could if I were flying on a commercial airline,” explains Baker. “I may have been piloting the aircraft myself, but I still needed a ride once I landed. There were a few commercial products that provided this service for around $1,000 a month, but that wasn’t a realistic solution for friends and family. I got in touch with the