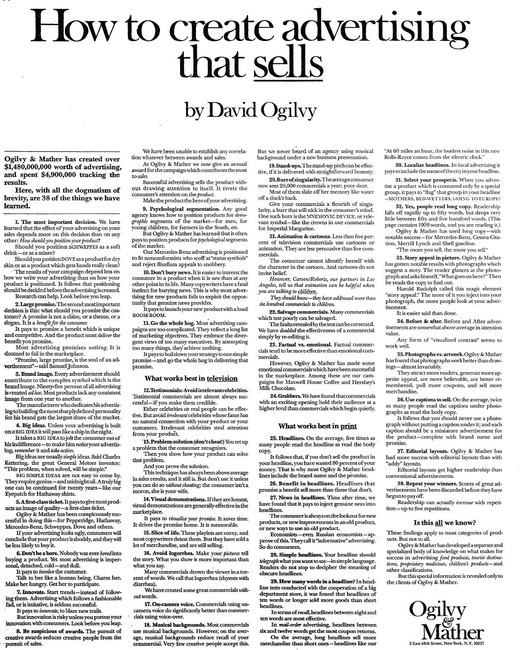

1,900 word ad “How to create advertising that sells” written by David Ogilvy that ran in newspapers in the 60’s and 70’s for Ogilvy & Mather.

You’re reading Signal v. Noise, a publication about the web by Basecamp since 1999. Happy !

1,900 word ad “How to create advertising that sells” written by David Ogilvy that ran in newspapers in the 60’s and 70’s for Ogilvy & Mather.

From our Campfire chat room:

Advertising is as close to a performing art as it gets in business. And as any dancer or actor or singer will tell you, even the most brilliant careers are riddled with booby traps, things that can blow a dream apart worse than a Claymore mine in a shopping mall. Advertising is like that. There will be times when it tries to dishearten you. Discourage you. Break you…

Love the triumphs. Love the disappointments. The ups and the downs, the sweet and the bitter … Whether it comes to life or not is up to you.

A human-powered airplane. That was the challenge set forth by Henry Kremer in 1959. For 18 years, nobody could do it. But within six months of trying, Paul MacCready built and flew his Gossamer Condor (below). The difference in his approach: While others needed a year’s worth of effort for each test flight, he created a plane that he could fly, fix, and fly again in mere hours. Aza Raskin explains:*

The problem was the problem. MacCready realized that what needed to be solved was not, in fact, human-powered flight. That was a red herring. The problem was the process itself. And a negative side effect was the blind pursuit of a goal without a deeper understanding of how to tackle deeply difficult challenges. He came up with a new problem that he set out to solve: How can you build a plane that could be rebuilt in hours, not months? And he did. He built a plane with Mylar, aluminum tubing, and wire.

The first airplane didn’t work. It was too flimsy. But, because the problem he set out to solve was creating a plane he could fix in hours, he was able to quickly iterate. Sometimes he would fly three or four different planes in a single day. The rebuild, re-test, and re-learn cycle went from months and years to hours and days…

So what’s the lesson? When you are solving a difficult problem, re-frame the problem so that your solution helps you learn faster. Find a faster way to fail, recover, and try again. If the problem you are trying to solve involves creating a magnum opus, you are solving the wrong problem.

[Thanks to Tim for the link.]

MacCready is a fascinating guy. Some deeper digging — this 1991 interview with MacCready and “Unleashing Creativity,” a keynote presentation he made in 1995 — reveals more interesting lessons from the Gossamer project…

Trust your subconcious

In 1976, MacCready was in debt. He had guaranteed a friend that he’d repay a $100,000 loan he used to start a company that failed. Something in his brain clicked when he realized the £50,000 Kremer Prize for human-powered flight was still up for grabs. The value of the British pound in 1976 was exactly $2. MacCready credits his subconscious with making the connection. “The prize equaled the debt! Human-powered flight suddently became attractive, motivating,” he said. “The only big ideas I ever came up with arose from daydreaming.”

Whenever he hit a sticking point with the project, he gave up on it and went off and did other things. “This is a fairly acknowledged way of coming up with inventions,” he explained. “You get yourself all full of details, still can’t figure out how to overcome the problems, and you give up and then, suddenly, an idea pops into your mind, or a dream, or something else you are doing, shows you a way to handle it that you would never have gotten by sitting in your office and grinding along in a good linear fashion. It requires getting away, looking at it more dispassionately, or not even looking at it.”

Dropping the topic from his “conscious priority list” led him to a hobby study on a different topic, observing the speed and turning radius of various soaring birds. “The subconscious again shouted, ‘Aha!’ The light bulb of innovation glowed over my head. And the Gossamer aircraft concept emerged,” he explained.

Naiveté can trump people, time, and resources

Other teams had more people, time, and resources. They made sophisticated aircraft that didn’t come close to winning the prize. He said, “That proved that those approaches were not very good. Plus I couldn’t aspire to make such complex, elegant aircraft as they had made.”

In fact, MacCready felt his inexperience was actually a strength. “Each British team had a specialist for every discipline, and so the wing structure was constructed starting from conventional structural design by an excellent structural engineer from the aircraft industry,” he said. “I have no background in aircraft wing structure. Thus, in my naiveté, I started from first principles (with some insights left over from building indoor model airplanes in the 50s and hang gliders in the early 70s), pretended I never saw an airplane before, and came up with the Gossamer Condor approach that permitted a 96’ span vehicle to weigh only 55-70 lbs. The British engineers also knew about indoor models and hang gliders, but they knew so much about their specialty that an easier approach was not apparent.”

“I pretended I never saw an airplane before and came up with the Gossamer Condor.”

The advantage of inexperience is a concept others have pointed out too. Teach for America founder Wendy Kopp: “I just think there’s actually a huge power to inexperience. In the context of deeply entrenched problems that many people have given up on, it helps to not have a traditional framework so you can ask the naive questions. That can help you set goals that more experienced people wouldn’t think are feasible.”

These hand-painted bells from DringDring add even more fun & exuberance to a bike ride!

A cartoon by Hugh MacLeod: “The idea comes from a core value taken right off [37signals’] homepage. They use a lot of blue and green in their graphic design, so I went with something blue-greeny.” Printable version also available.

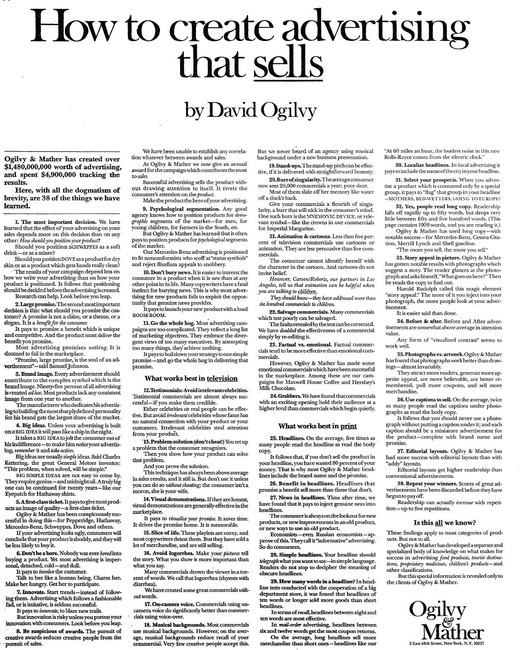

Customers want to actually use a tool before giving up their info. So it’s interesting to see more and more sites letting you do the thing first and moving to collect your info later (or not bothering at all)...

Optimizely

Optimizely bills itself as “A/B testing you’ll actually use.” The big call to action on the home page is a field to enter your website URL.

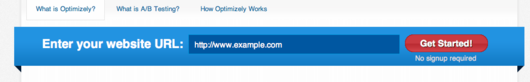

That takes you to a page where you can start annotating your website in order to set up your A/B test.

When you click save, that’s when the site prompts you to create an account.

Give the OK

Give the OK is an online feedback and approval tool. The home page offers a big “upload your first proof” button.

The resulting page gives you a link to share with your client. And that’s when the site encourages you to sign up for an account to track further iterations.

Continued…If you want to track further design iterations and harness the true power of Give The Ok, sign up using the form below.

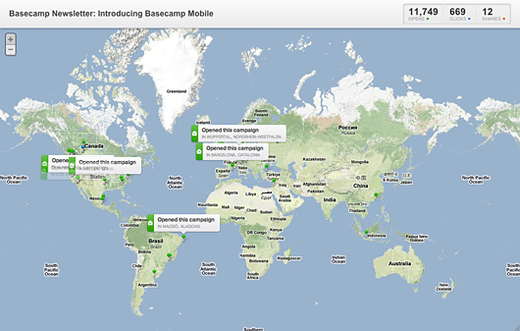

Campaign Monitor’s cool Worldview feature on our latest Basecamp Mobile newsletter

It takes 77 steps to make an Emeco 1006 chair. It’s made from 12 different sections by 50 people and they need 8 hours to do it. At each step along the way, the chair is ground to smooth out the welds and create a seamless look. The end product is nearly indestructible and built to last for 150 years.

Once found on destroyers and submarines in the 1940s, this article in Metropolis talks about how the chair has become a favorite of designers. In fact, Philipe Starck agreed to offer updated designs for no fee.

“I was worried that Philippe would want a huge fee to design for us, but he didn’t even discuss money until I told him that I couldn’t afford to pay him anything. I offered him a stake in the company. He said he didn’t want one.” Instead Emeco will pay Starck an undisclosed royalty. “He could’ve taken his designs to Steelcase and made a big, fat fee.”

Starck chose to design for Emeco for a simple reason. “I have always admired the way the Emeco chair is put together,” he says. “I thought if I could design a line of furniture that becomes a classic like that chair, then I would be doing something great. I have designed a great number of things I am not proud of, and they are no longer around. I want to design things that are here forever. I think it’s time to stop wasting what’s on the planet.”

There’s more on the Starck collaboration at the Emeco site. He writes, “It is a chair you never own, you just use it for a while until it is the next person’s turn. A great chair never should have to be recycled. This is good consideration of nature and mankind.”

The site also offers a neat documentary on the company and its design process. It talks about the “ping ponging” between designers and manufacturers and how the company builds dozens of actual chairs as prototypes before finalizing a design. One designer says, “Sometimes you don’t get around to doing the final drawings. Sometimes the chair is the drawing.”

Also revealed in the doc (though perhaps just legend): The 1006’s seat was molded after Betty Grable’s bottom.

Going back to the Metropolis article, it mentions seven ads Emeco ran in Fortune back in the 1950s.

Each one depicted a different sculpture by Rodin; above the bronzes, in large letters, the ads read: “Sculpted Masterworks.” The name Emeco was in small letters at the bottom. “A lot of people called, asking, “What do you make?’” recalls Emeco’s chief operating officer at the time.

Sounds like a forerunner to Apple’s Think Different campaign.